Pau Waelder

Serafin Álvarez is an artist and researcher based in Barcelona, who explores themes and concepts associated with liminality, non-human otherness, the journey into the unknown and changes in the perception of reality; and how these are imagined and depicted in contemporary popular culture, with a particular interest in science fiction and fantasy film and video games. Encompassing 3D animation and interactive simulated environments, sculpture and installation, his work has been exhibited internationally.

The work of Serafín Álvarez has been featured in Niio in the artcasts Worlding with the Trouble (curated by Fabbula) and Heterotopias, alongside other international artists. The recent artcast Places of Otherness brings together four of his works, spanning the latest five years of his career. On the occasion of this presentation, we talked with him about the process and concepts behind his work.

Serafín Álvarez, Umbral Autoplay (Video Version), 2018

You have stated that the inspiration for Maze Walkthrough comes from the experience of going from one airport to another while you were producing a previous project. Would you say that both airports and videogame environments are “non-places” meant for endless circulation?

Indeed, airports have often been associated with Marc Augé’s concept of non-place, but I would not put, generally speaking, video game environments in that category, since they are, for many players, places where meaningful relationships are established. In any case, when I did these works I was not so much thinking about the concept of non-place as about liminality. In both cases I looked at certain architectural spaces (corridors and airports) as spaces for transit, circulation, change. Spaces that have not been designed to be inhabited, but to connect other spaces.

“What interests me most about science fiction is the speculation about the unknown and the ways of representing it. That unknown can be an Other, a place, a state of consciousness, a mutation, and so on.”

You are interested in science fiction as an exploration of the Other. In your work, this Other would be the space itself, strange and unpredictable?

One of the things that interests me most about science fiction is the speculation about the unknown and the ways of representing it. That unknown can be an Other (understood as someone different, whether human or of another species), but it can also be a place, a state of consciousness, a mutation, and so on. In my work I have looked at multiple resources that science fiction uses to represent what we don’t know: visual effects, soundtracks, costumes… but you are right that in most of my work there is an important spatial component, an active interest in spaces of otherness.

In your works you seek to create an experience, which becomes immersive by allowing the viewer to wander freely through the spaces and free themselves from the impositions of gameplay. How do the sculptural elements you create for exhibitions in physical spaces participate in this immersion?

My work is predominantly digital, but when I exhibit it I’m very interested in its physical dimension. I like sculpture very much and I try to incorporate in my own work that physical relationship between bodies that I enjoy so much when looking at physical objects in the real world. On the other hand, digital work can become a bit schizophrenic, because you can edit and polish details ad infinitum, try one thing, undo it and try another one endlessly. Working with matter is different, it allows me and encourages me to be more intuitive, to let myself go, to establish a less controlling relationship with the materials, and I personally think that brings very positive things to my work.

Serafín Álvarez, A Full Empty, 2018

You have distributed your work as downloadable files that the public can buy for whatever price they want, even for free. What has this kind of distribution meant for you? Do you see other ways of distribution that would be conducive to your work, particularly because of its identification with the language of videogames?

I have two pieces of interactive software on itch.io, an interesting platform for independent video games with a very active community. I usually work with physical exhibitions in mind, but distributing part of my work digitally has allowed me to reach other audiences; it has given me a certain autonomy to show and make my work known without having to depend exclusively on institutions, galleries and curators; and being attentive to digital platforms for art distribution has allowed me to get to know the work of a large number of very interesting artists who are active online although they may not have as much presence in the conventional channels of contemporary art.

It seems that Maze Walkthrough has been better understood in the field of videogames than in the contemporary art world. Do you think this is due more to the aesthetics or to its “navigability”?

I don’t know if better, but different. When I published Maze Walkthrough it was reviewed in some media outside the field of contemporary art and it was very well received. Many people wrote to me, many people commented and shared both the piece of software and the collection of corridors at scificorridorarchive.com that I made while conceiving the project. Audiences around science fiction and video games have always interested me, and that such audiences valued my work was something that filled me with joy. One of the things I liked most about that reception was to see people enjoying the piece in a different way than the contemporary art audiences I’m used to, which tend to look at the work in a reflexive way, pondering possible interpretations. I’m very interested in hermeneutics, but it was refreshing to also see people enjoying Maze Walkthrough more from experience than intellect.

Serafín Álvarez, Maze Walkthrough, 2014

A Full Empty, the video you presented as part of the artcast curated by Fabbula, shows a world in which nature has run its course after an industrial era that fell into decay. Do you see in this work an interest in dealing with environmental issues through simulation, or do you continue to explore spaces linked to science fiction narratives?

Both. This work is based on two fictional texts: Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker and, especially, the novel Roadside Picnic by the Strugatsky brothers on which Tarkovsky based his film. Both texts are about a forbidden zone to which humans have restricted access and which develops its own ecology, and while making that video I found myself thinking about what the planet would be like once we are no longer here.

“Science fiction and video game audiences have always interested me. I like to see people enjoying the piece in a different way than the contemporary art audiences I’m used to.”

You are interested in freeing the viewer from the tyranny of the camera, but there’s actually an interesting aspect to the camera movement in your work. Normally it’s a forward traveling sequence, following the logic of video game exploration, but in A Full Empty it is, conversely, a backward traveling, which gives it a more cinematic character. Is this a conscious decision in the creation of this piece? Have you thought about working more with camera movements in future works?

Yes, of course it was a very conscious decision. In Roadside Picnic the scientists who study the forbidden zone explore it with great care, because it is full of deadly traps. They have developed hovering vehicles with a “route memorizer” system that, once they have finished an exploration journey into the zone, return them back on their steps in an automated way to reduce the danger, undoing on the way back the exact same route they did on the way out and therefore without falling into the traps already bypassed. The video is influenced by this automated journey of return after having entered a strange place in search of something.

I’m sure I’ll continue working with camera movements, it’s something that fascinates me. Right now I’m involved in developing live simulations that are much less cinematic than the video A Full Empty, but I still think and care a lot about camera movements, no matter how simple they are. Moving the camera is a wonderful expressive resource.

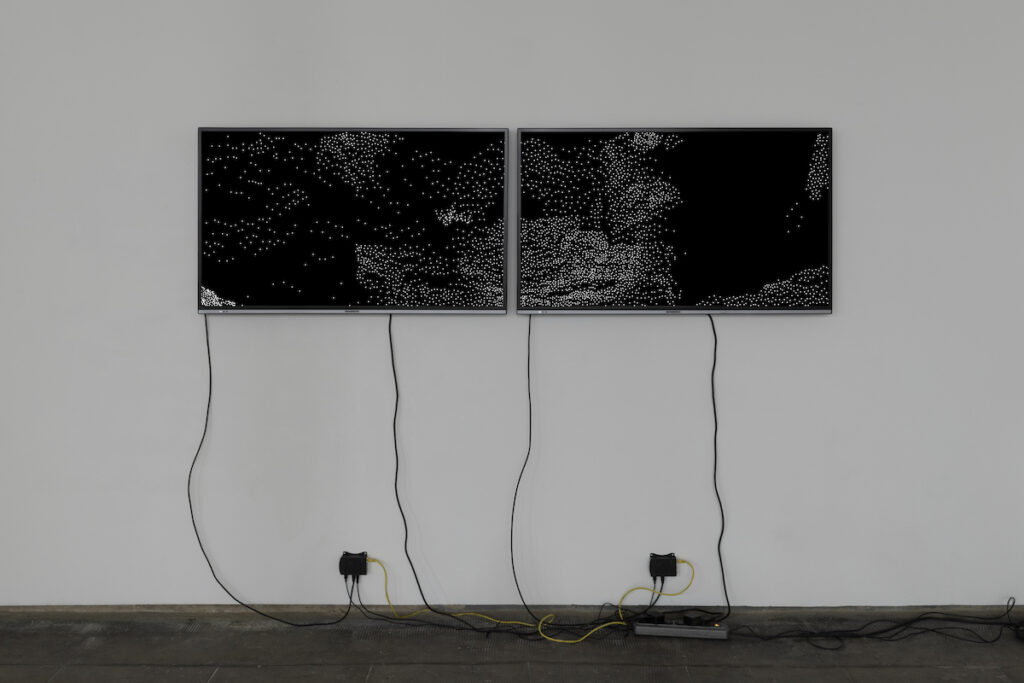

Serafín Álvarez, Now Gone, 2020

In Now Gone you adopt a different aesthetic, which resembles the point clouds created by 3D scanners, to show a mysterious cave inspired by the film Prometheus and the universe of H.R. Giger. What led you to this aesthetic and how would you link this piece to your other works?

The link with other works is a similar interest in the journey, in the passing from one place (or condition, or state…) to another. Also, the arrangement of “intertextual elements”, vestiges that refer to fictional stories as if they were a kind of archaeological objects… although it is true that the aesthetics of Now Gone is different from my previous works. Now Gone was born from an invitation to participate in a publication, Today is a Very Very Very Very Very Very Very Gummy Place by Pablo Serret de Ena and Ruja Press. They sent me a very ambiguous map and asked me to make something from it. My proposal was to build an environment with video game technology. Since the publication was going to be edited in black and white I started to try things using this limitation in a creative manner and, after several experiments, something that worked very well for what I wanted to achieve was to render the images using a 1-bit dither (a graphic technique in which there are only black or white pixels organized in such a way that it produces the illusion of grays, similarly to Ben Day dots in comics). I’m very pleased with the result, in fact I soon returned to a very similar aesthetic in a later work, A Weeping Wound Made by an Extremely Sharp Obsidian Knife, and I’m currently looking at different ways to develop it further in the future.

Fabbula specializes in curating Virtual Reality projects and immersive experiences. In relation to your work, how do you see the possibilities offered by current VR devices for the dissemination of digital artworks?

At the moment I haven’t seriously started working with VR. As I mentioned in a previous question, I’m very interested in the relationship between the work, the viewer and the physical space, but generally speaking VR experiences tend to remove that physical space. I’m sure there are interesting ways to incorporate it, but for the moment I haven’t worked in that direction yet.