Niio Editorial

Jinsil Lee is a visual artist based in Seoul, South Korea. She earned a BFA degree in 2019 from School of Visual Arts, New York City, where she initially developed her photography work. She later on moved to Seoul, where she continues her career as an artist while working as a content specialist at Tesla Korea. Her work has been featured on the Samsung US website and Samsung Mobile USA social channels, and she has also participated in group shows such as the Naver Z Metaverse Exhibition (2022), Pulse Art Fair in Miami (2019), and School of Visual Arts Mentor Show (2019).

On the occasion of her first solo artcast on Niio, Transcendence, we talked with Jinsil about her creative process and the way she transforms scenes captured in her daily environment into mesmerizing abstract compositions.

Jinsil Lee. Dream of a summer night, 2019

You studied at the NY School of Visual Arts and currently live and work in Seoul as a visual artist and content specialist. Both New York and Seoul are vibrant cities, each with their own pace and culture. What has been more inspiring to you from your experience living and developing your career between the US and South Korea?

New York and Seoul are very similar and different cities. Both cities are full of their own charm, and both have been very inspiring to me in different ways. I grew up in Korea, so I’m more influenced by Korean culture in terms of the way I think and the language, but it was in the US where I really started to pursue art. I was able to explore art more freely in New York with its huge art scene, various art fairs, galleries, and artists, and this has greatly influenced my work today. Both cities have influenced me in different ways. Seoul has influenced me as a person, and New York has influenced my artistic work.

“I’ve lived in cities all my life, so I have a longing for nature.”

Your work is based on photography, yet it becomes a moving, abstract image. Can you explain to us your creative process? How does the transition from the captured image to the final composition come about?

I’ve been drawing since I was a kid. In my teenage years, I mostly painted in oils, and I loved the freedom to express whatever I imagined on the canvas. Then I started photography and applied my painting style to the medium of photography. I took a series of photographs and used tools like Photoshop to create short videos, and then I moved on to working with footage shot in video format.

Jinsil Lee. Sunset Town, 2018

Scenes from daily life and natural landscapes are sources of inspiration in your work. What are you most attracted to? Do you consider the scenes in front of you in terms of their aesthetics (colors, light, movement) or do you also consider their context, the meanings and stories that underlie the image you are capturing?

I’ve lived in cities all my life, so I have a longing for nature. I work and live in a big building in the city, but I question every day whether this environment is right for our bodies and minds, so when I’m close to nature, I feel an indescribable sense of awe. I think about this a lot, especially when I’m at the beach and I’m looking at the water moving like it’s breathing and the sunlight shining on it, and I realize that it’s so much like a human being, and I think about how long they must have traveled to get to where I am, and I think about how the moment that I’m in with them feels like a miracle, and it’s amazing. The visual beauty in front of me inspires me, but I think it’s probably the backstory that has a bigger impact on me.

Jinsil Lee. 20 18, 2018

Abstract art seeks the essence of things and at the same time removes the viewer from any reference to a specific time or space. What do you find most interesting about focusing on abstraction? What do you think that might be missing from the first-hand experience you get while capturing the original images?

I think there’s a lot of power in abstract art, and the reason I loved painting as a kid was that I was free to express my thoughts on a white canvas. I think abstract art, similar to the experience of painting, gives the audience a bigger room to run around in by removing the boundaries, and that’s the power of abstract art, that other people can see what I’ve imagined and they can develop their own imagination. That’s how we connect through art, and I think it’s very similar to nature, where everything is connected organically. So I try to make the forms as minimal as possible, and then I use the power of color to replace them, so that the audience doesn’t see them in their rawest state, but on the other hand, they see them in their most basic, unclothed form.

”The power of abstract art is that other people can see what I’ve imagined and they can develop their own imagination.”

Water, oceans, fluids, are common elements in your work. This is often combined with symmetrical structures, creating a certain tension between order and chaos, staticity and fluidity. What do you find most interesting about this tension between opposites? Could there be one without the other?

I love the book White by Hara Kenya, and there’s a quote in it that goes something like this. “The black color of type is only truly valuable when it is paired with the white it is based on.” I believe that two opposites are more valuable when they coexist, like you can only feel joy when there is sadness, and that’s why I like to play with this idea. In fact, my biggest inspiration is nature, but capturing it as a pixel-based digital photograph and editing it through digital tools, I think this process is very similar to human life. There are quiet people and there are loud people, there are people like me who are good at drawing but not so good at talking, and there are people who are better at expressing themselves through words than through drawings. I think my artistic process is a lot like our lives, where we have these opposites living together.

Jinsil Lee. 4AM, 2019

While your compositions are abstract and rationally geometric, the titles of your artworks suggest a narrative, which in some cases is expressed with words, as in These Foolish Things. Can you elaborate on the use of narrative in your work?

One of the most important things in my life is music. I feel unimaginable happiness from a favorite song and can be immersed in that emotional state for long periods of time. So when I start listening to a song, I usually memorize the lyrics from start to finish, and then I take those lyrics and rearrange them or turn the words into something that expresses my thoughts and use them in my artwork. I think it’s interesting that in this process, I’ll be thinking about the song while looking at my work, but I’m taking the audience into a world that I’ve “recreated”.

“My artistic process is a lot like our lives, where we have these opposites living together”

Sound and music also play a role in your work, which is sometimes silent, and sometimes features a music score or the sounds of the environment you recorded. Can you tell us a bit more about the connection between images and sound, and what leads you to choose whether the piece will be silent, with music, or ambient noise?

I often meditate, and sometimes music helps me to focus, and sometimes I’m able to focus more deeply when there is no sound at all. When I work on my art, I feel similar to when I meditate, sometimes I work with music and sometimes I work in a silent environment. For each piece, I choose sound to support the audience’s visual experience, and sometimes I choose silence so that the audience can focus on the visual experience alone.

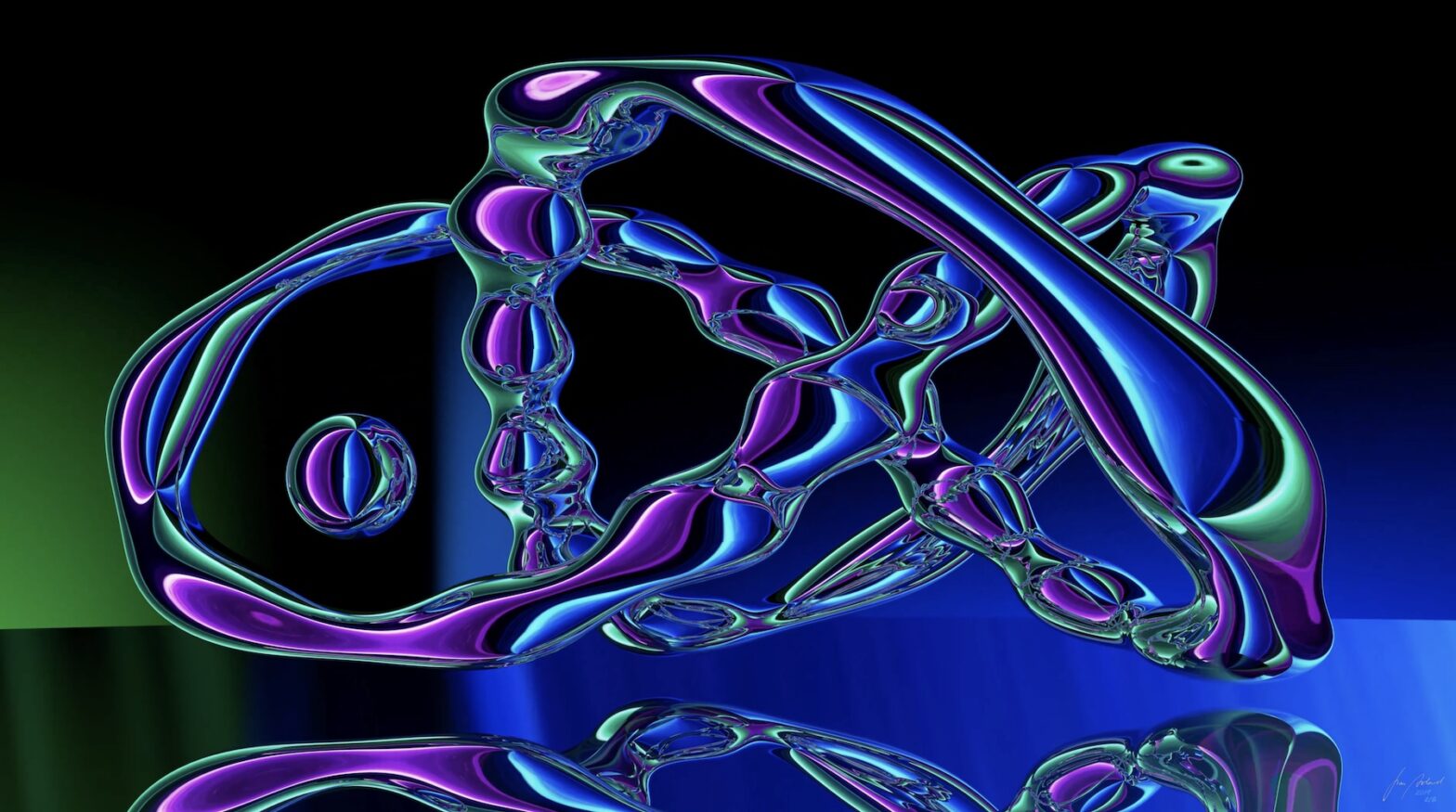

Jinsil Lee. In Your Orbit, 2019

The growing influence of AI in the visual arts offers artists the possibility to work with source material that doesn’t exist, but is created by a prompt. Are you interested in incorporating this technology into your work, for instance to start with an AI-generated video and then turn it into an abstract composition, or else use real footage and transform it with the aid of AI tools?

100%. I consider my work to be a 3 way collaboration between nature, myself and digital technology. I am quite interested in how digital cameras capture and read moments. For example, the actual color I remember is often not the same as the color the digital camera reproduces, but I find the process and how it works fascinating, so I use it as it was captured. In this context, the idea of AI generating an image based on the data it has stored over the years, with prompts from me, is very interesting.

“I want to create a work of art in which I and the AI imagine a universe that I can’t actually photograph.”

It’s a vague idea, but I want to create a work of art in which I and the AI imagine a universe that I can’t actually photograph. If so, I’m very excited to see where that AI’s data comes from and how amazing it would be to see how it came to meet me.