Pau Waelder

The 27th International Symposium on Electronic Art took place in Barcelona from 9 to 16th June, bringing to the city a community of more than 750 experts in art, science and technology and hosting 140 presentations made by experts in the field, 45 institutional presentations, 40 talks given by artists, 23 screenings, 18 posters and demos, 16 round tables, 13 workshops, and 13 performances. The main organizer of the event was the Open University of Catalonia (UOC), in partnership with ISEA International, the Government of Catalonia and the main cultural and political institutions in the region.

Directed by Professors Pau Alsina and Irma Vilà from the UOC, the symposium included a densely curated art program with several exhibitions in the city that can be visited during the summer. While organizing the symposium, Alsina and Vilà established collaborations with the major cultural institutions in Barcelona, resulting in a particular presentation of new media art that has permeated the local contemporary art scene, establishing a dialogue with the curatorial approaches of the different venues. This interplay can be seen in the three major exhibitions spread over the city: What is Possible and What is Not at La Capella, Possibles at Recinte Modernista Sant Pau, and The irruption at Santa Mònica. While the most established art institutions in Barcelona, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA) and the Center for Contemporary Culture (CCCB), hosted the talks, lectures, and a series of performances, the three spaces have had the task of collectively presenting an overview of artistic creation in the field of art, science, and technology (AST). The result is particularly interesting, as it has brought about a rather unprecedented variety of formats, themes, and approaches to creating and presenting art made with and about digital technologies and scientific research.

The exhibitions in Barcelona feature three different forms of presenting new media art: a setup similar to contemporary art biennials, a process-oriented, artist-in-residence environment, and a new media art festival exhibition.

In my role as Chair of Artworks of the symposium, I oversaw the whole selection process of the more than 600 artistic projects presented in an open call that exceeded all our expectations. The peer-review process involved more than 200 scholars, artists, curators, and art professionals to whom ISEA and the Barcelona team are deeply indebted. The selected artworks were presented to the curators of Santa Mònica and La Capella, with the third exhibition putting together a selection curated by Irma Vilà, a presentation curated by myself through Niio, and part of the BEEP Collection. The curators in the respective venues integrated the artworks they selected into the narrative they had developed for their spaces, which organically led to three different forms of presenting new media art: a setup similar to those of contemporary art biennials, a process-oriented, artist-in-residence environment, and finally the kind of exhibition one typically encounters at a new media art festival. While these approaches could have found a more dialogical setup in a shared space, the fact that they constitute three separate proposals makes it an enriching experience for a visitor who attends all three exhibitions knowing that all the artworks are related to the field of art, science and technology.

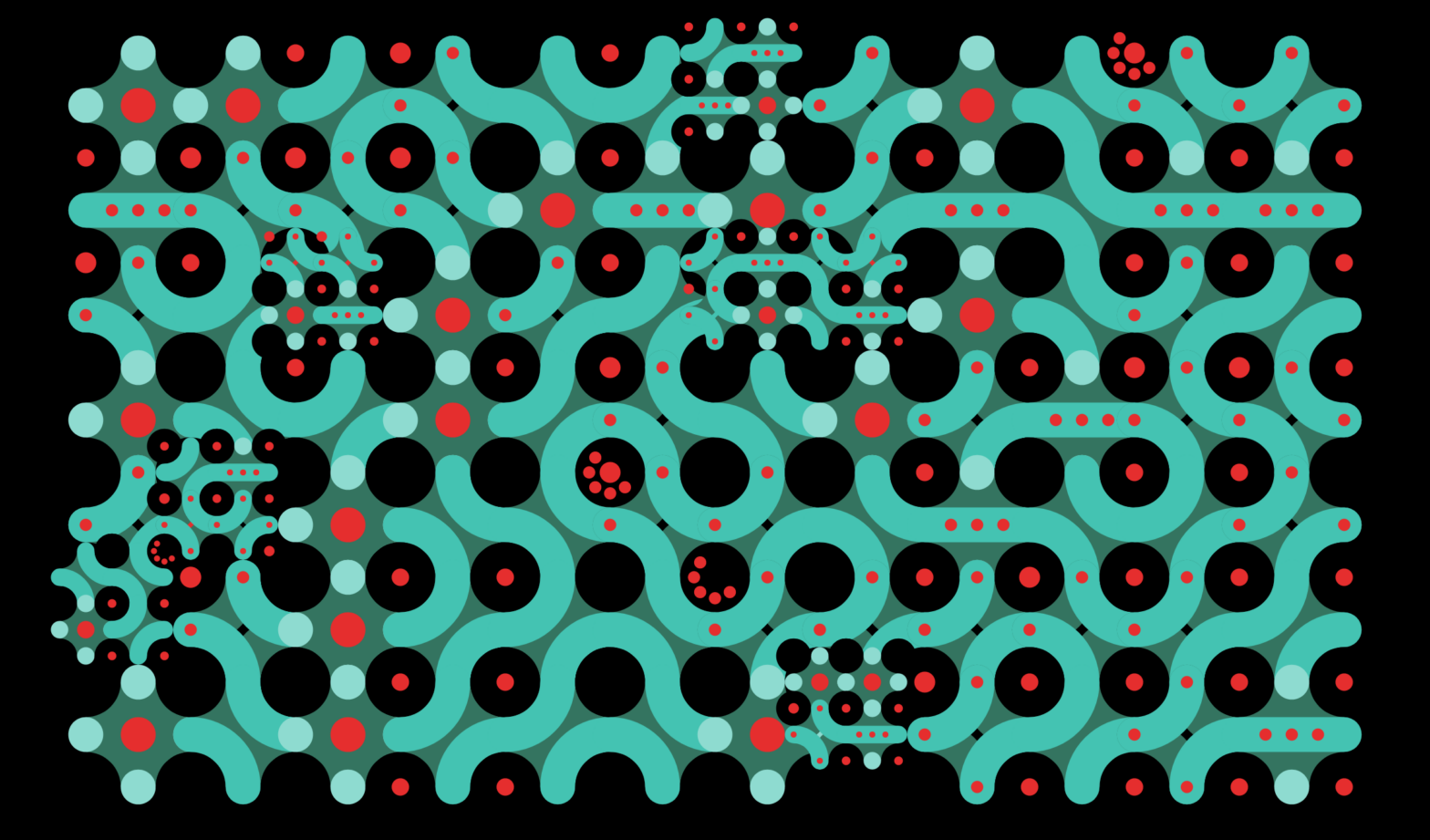

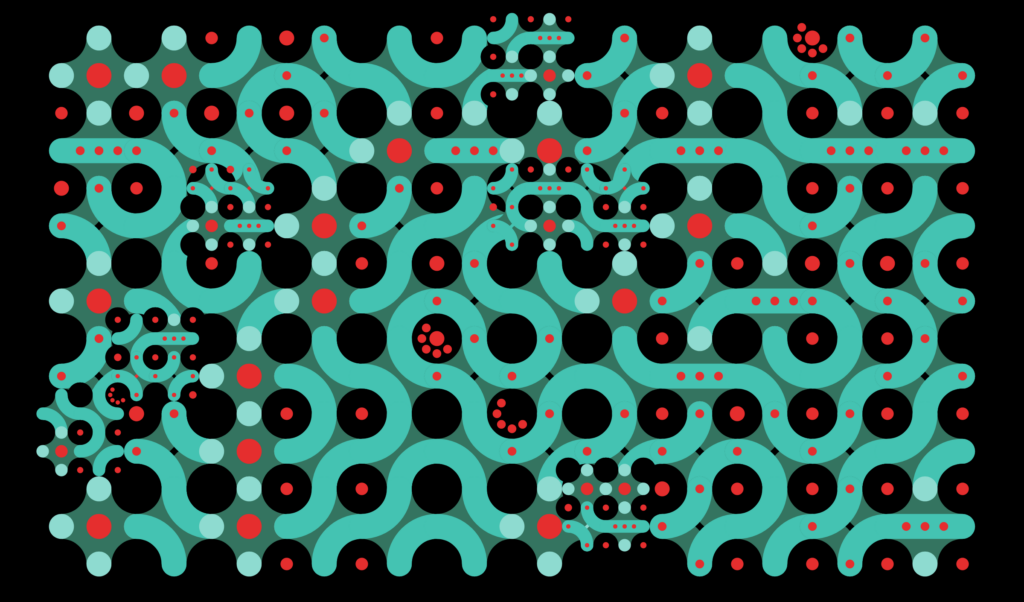

Antoine Schmitt. Generative Quantum Ballet 21 Video Recording, 2022. Artwork included in the selection by Niio at the exhibition Possibles.

Santa Mònica: new media art as contemporary art

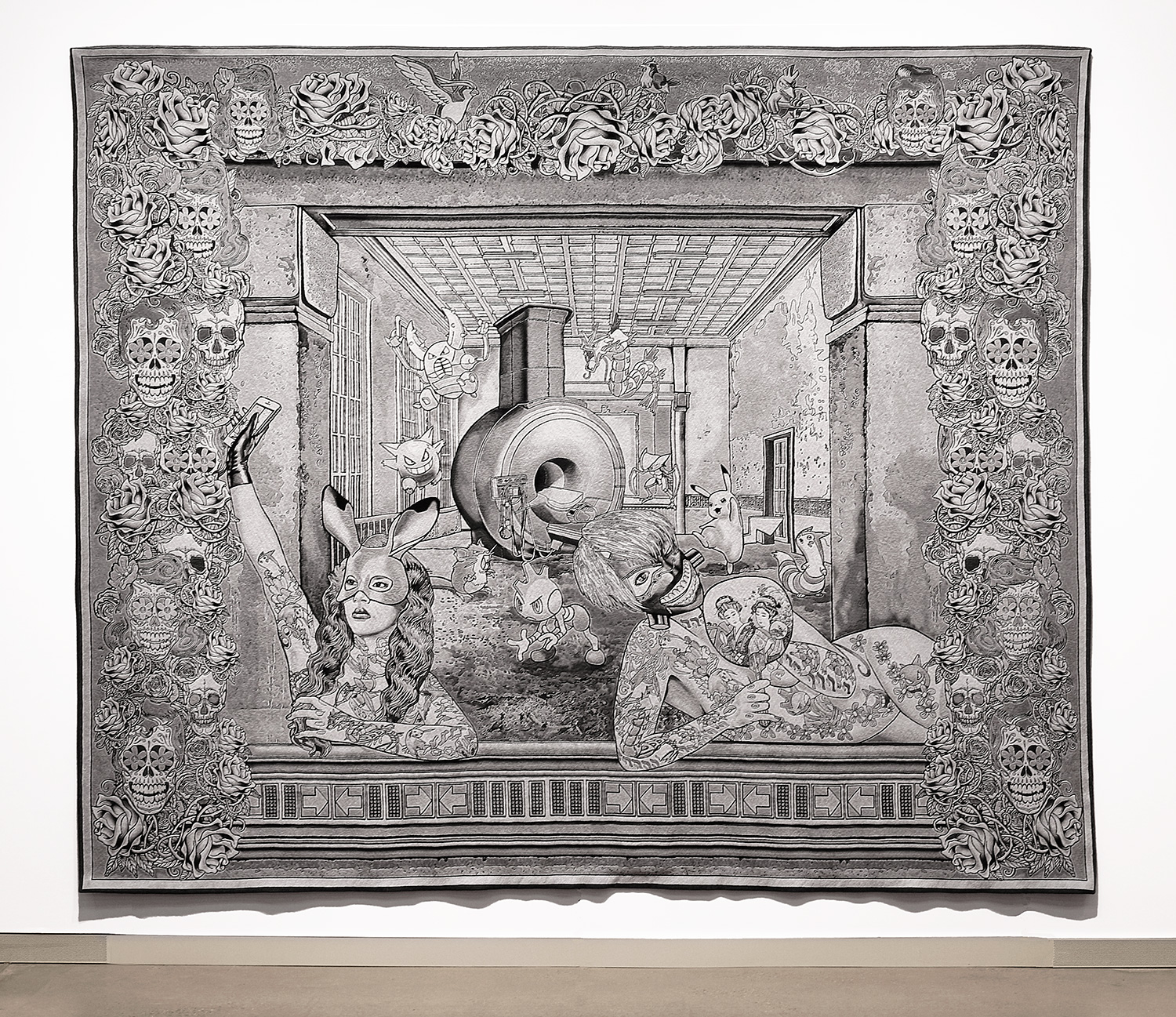

The curators of Santa Mònica, Marta Gracia, Jara Rocha and Enric Puig Punyet, selected more than twenty artworks from the open call which they grouped under an overarching theme addressing the conditions of life on our planet after the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Climate change is a prevalent subject in this exhibition, as exemplified by It will happen here, in Barcelona, an algorithmic cinema installation by Roderick Coover, Nick Montfort, and Adam Vidiksis that elaborates a never-ending narrative about the impact of rising waters, which will entail migration and extinction. The piece is presented as a large-scale projection that takes half of the second floor of the former convent. Other artworks address our relationship with the planet from the wider perspective of the anthropocene, such as Quadra Minerale-Rare Earths by Rosell Meseguer, which connects mineral colonization with our dependence on digital technologies, and Tools for a Warming Planet by Sara Dean, Beth Ferguson, and Marina Monsonís, which consists of a crowdsourced collection of current and speculative tools for adapting to life in our changing world, contributed by designers, artists, activists, and scientists. These artworks are presented in the form of archives and displays that remind of the classical cabinet of curiosities.

Climate change, the Anthropocene and our social and spatial relationships during the pandemic are prevalent subjects in the exhibition at Santa Mònica

Our social and spatial relationships during the pandemic are also a recurring subject in the exhibition, with artworks such as Muted by Lauren Lee McCarthy, which collects several performative pieces she carried out during lockdown and afterwards, establishing different kinds of mediated communication with friends and strangers. McCarthy’s work takes the form of an installation with a double bed and several digital devices displaying the documentation of these performances. Also related to the pandemic, #See You at Home – The Domestic Space as Public Encounter by Bettina Katja Lange, Uwe Brunner, and Joan Soler-Adillon creates an immersive and interactive installation based on a series of 3D scans of people’s domestic spaces collected during lockdown, which has evolved into a reflection on the boundaries between the private and the public. While the exhibition, as can be expected, features numerous screen-based artworks and some VR environments, the overall experience is closer to what one might expect from a contemporary art biennial, with a predominance of objects, prints, and video installations.

La Capella: work-in-progress

The artistic director La Capella, David Armengol, chose to combine the presentation of a selection of artworks from the ISEA open call with those of the artists participating in Barcelona Producció, a yearly program dedicated to promote local talent through grants for research and production. The result is a well-balanced combination of artistic projects, all of which are characterized by their processual nature, be it as reactive sculptures, algorithmic animations or data-driven visualisations. Here it is telling that in most cases the artworks selected by ISEA reviewers cannot be told apart from those of local artists experimenting with technology. For instance, Anna Pascó’s ZENZ(A)I, a neural network that creates sayings by collecting meteorological data from different locations, could well have been part of the open call, as would also Estampa’s computer visions of an urban landscape or Mario Santamaria’s geolocative installation. The five selected artworks from the ISEA call turn towards nature and artificial intelligence in their reflections of the world around us, from Anna Carreras’ generative drawing Arrels, Yolanda Uriz’s stimulatingly olfactory Chemical Ecosystem, and the intimately analog Water Drop Viewer by Roc Parés, to the AI-inspired construction of language in d’Eco a Siringa by Josep Manuel Berenguer and the speculative robotics developed by Mónica Rikić in Especies I, II y III. While the artworks in this exhibition are no less complete and fully functional than those in Santa Mònica, the setup and narrative of the show lead more clearly to considering them as works-in-progress, not unfinished but always evolving, and it that sense provide visitors with a different experience, in which the experimental, the potential, and in fact the possible take a more prominent role.

Sant Pau: the realms of the digital

The Art Nouveau historical building of Sant Pau hosts a temporary exhibition in a dark underground room that is actually an illustrative example of the kind of spaces where digital art has been shown in the context of new media art festivals over the last decades. Dominated by a large selection of artworks from the BEEP Collection, the largest collection of digital art in Spain, the exhibition mainly consists of screen-based works and installations, many of which are interactive, and creates an atmosphere densely populated by the lights and sounds emanating from the artworks. The BEEP Collection, started in 2006 by entrepreneur Andreu Rodríguez and directed by Vicente Matallana, features a wide spectrum of new media artworks by pioneers such as Peter Weibel or Analivia Cordeiro alongside established names in the field such as Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau, and Daniel Canogar, as well as younger local artists, such as Santi Vilanova, Mónica Rikić, and Alex Posada. Built year after year with individual acquisitions, it presents a sample of the main developments in new media art over the last three to four decades, with examples of video art, interactive art, bio art, generative art, artificial intelligence art, light installations and so forth. The presence of the collection’s pieces greatly contributes to give the exhibition this aura of a new media art festival both in the aesthetic qualities and the variety of the artistic projects.

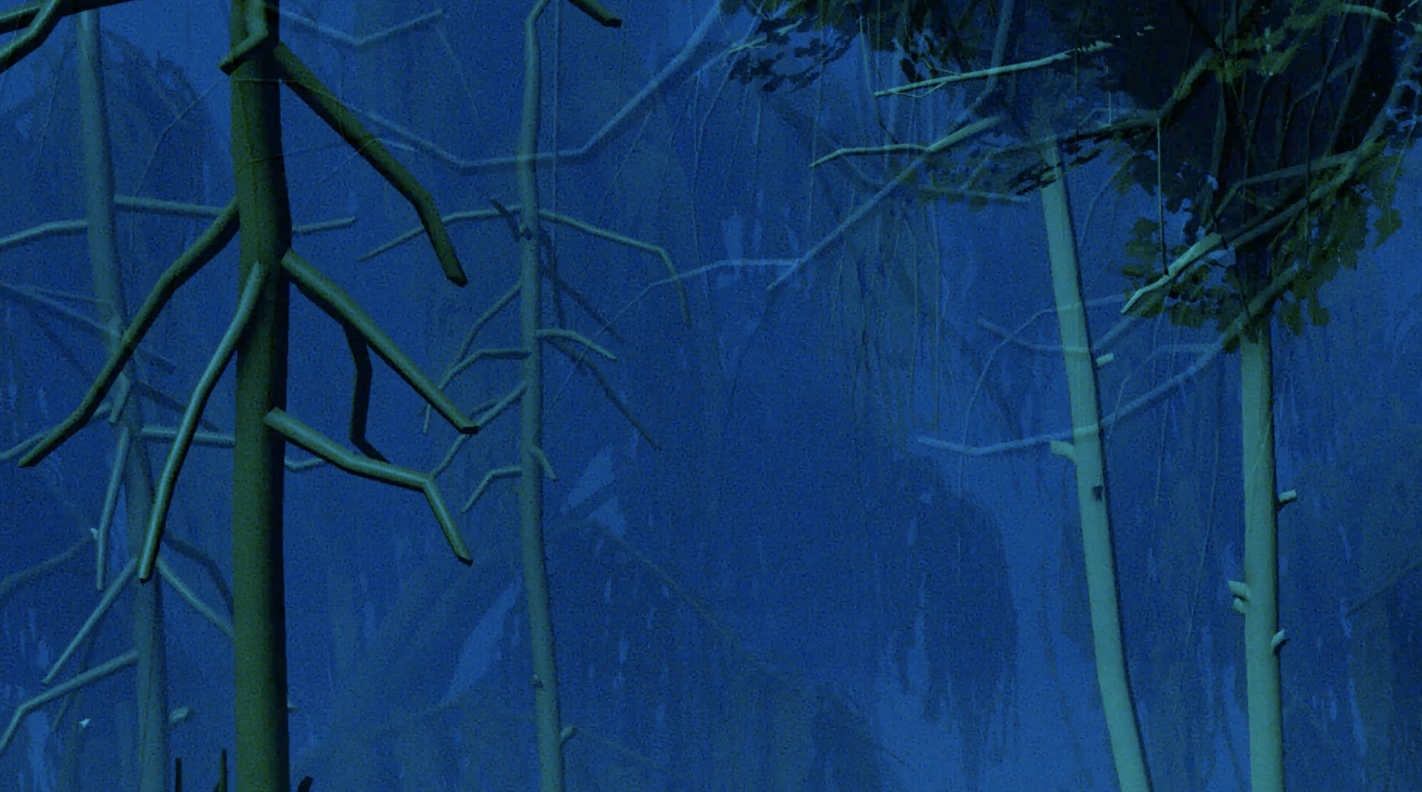

A selection of artworks from the ISEA open call curated by Irma Vilà explores the varied forms of perception of reality mediated by digital technologies. Liquid Views by Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss, a pioneering interactive work created in 1992 and updated for this exhibition, confronts viewers with their own image in a mesmerizing “mirror of Narcissus” that anticipated, 30 years ago, our current selfie culture and the appeal of tactile interfaces. Last Breaths by Linda Dement, Paul Brown, and Carmine Gentile develops a different form of register of the existence of a person. The last breaths of the artist George Schwarz, who died of a cardiac failure, were recorded. The audio values were turned into a 3D printed sculpture of living cardiac cells. Evoking loss and memory, the piece confronts the power of science with the inevitability of death and suggests a new way of perceiving an ephemeral, yet crucial moment in a person’s life. The living, interconnected system of a forest is consciously presented as an empty vessel in a series of 3D scans of a natural environment in Queensland (Australia) made by Keith Armstrong. Common Thread connects the deceivingly realistic rendering of the forest with the shallow perception of nature by Australia’s colonizers, as opposed to the profound understanding and rich mythologies of its original dwellers. This view can be compared to the ironic take on Artificial Intelligence created by Thierry Fournier in Sightseeing, a fiction about an all-too-intelligent AI whose task is to observe a beach through a CCTV camera, leading it to ultimately question what it perceives as well as its own purpose and existence. Finally, Paul Brown addresses a further stage in the perception of reality by elaborating in Quantum Chaos Set a visualization about the quantum world of uncertainty, through a photograph of felt fibres that undergoes continuous transformations generated by random sorting algorithm that repositions each pixel of the image.

A selection of artworks from the ISEA open call curated by Irma Vilà explores the varied forms of perception of reality mediated by digital technologies

The exhibition is completed with a presentation of artworks curated by myself on Niio. Following the themes of the symposium, I addressed the subjects of humans and non-humans, natures and worlds, and futures and heritages through a selection of video works displayed on a single screen. In Generative Quantum Ballet 21, Antoine Schmitt takes his interest in choreography and performance arts and his signature minimalistic visual element, the white pixel, to the realm of quantum systems in a generative artwork of which a video excerpt was shown. Jeppe Lange creates a beautiful and poetic narrative around perception in Le monde en lui-même, a video work that uses hundreds of post-impressionist paintings in a mesmerizing collage. Diane Drubay challenges our complacent perception of the world in times of climate change in Ignis II, an animation showing the transformation of a placid summer sky into a menacing storm in the span of 14 seconds, which correspond to the 14 years left until we reach a point of no return in our warming planet. Oblivion finds a visual representation in Frederik de Wilde’s Oh Deer!, an AI experiment showing a short clip of a deer being continuously processed by a Generative Adversarial Network that the artist modifies to progressively remove information, until nothing is left but a grey square. Sabrina Ratté addresses both nature and memory in FLORALIA, a speculative fiction about a virtual archive room preserving extinct plant species. The selection concludes with Snow Yunxue Fu’s Karst, a virtual reality artwork that takes us to spaces that are beyond human reach, questioning whether the ability to experience them in a simulated environment may expand our notion of the reality around us.

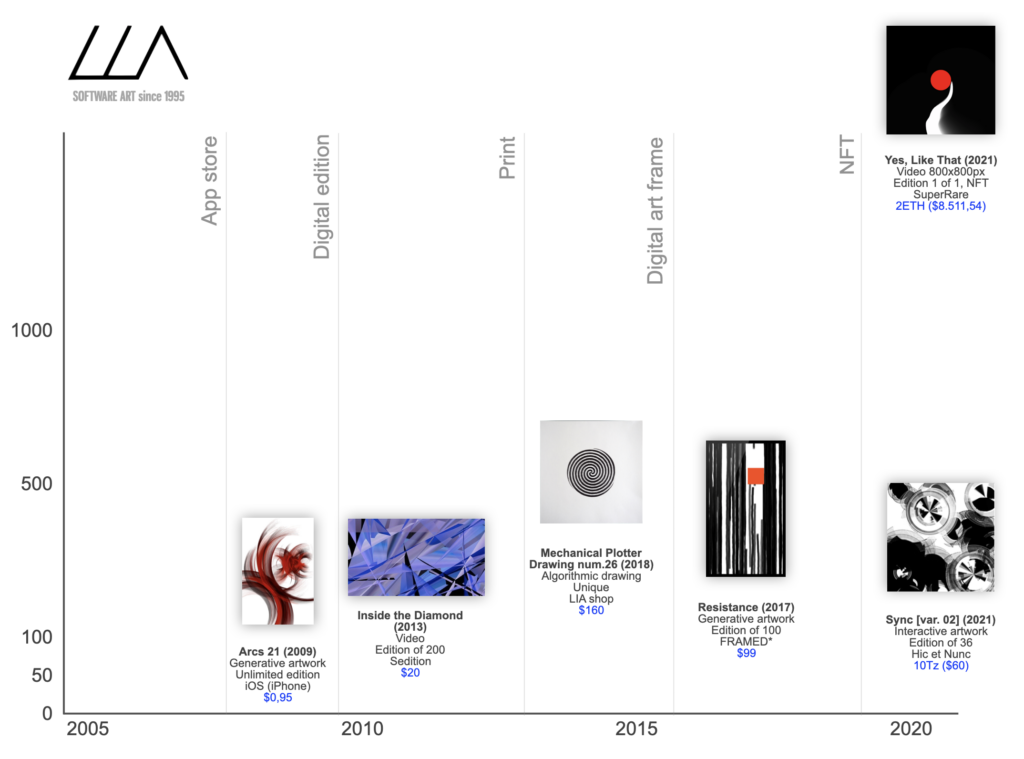

Digital art in the art galleries

Beyond these three main exhibitions, the presence of artists working with digital technologies in commercial galleries exemplifies the increasingly normalized presence of new media art in the contemporary art market. Anna Carreras presented her generative artworks in a solo show at Ana Mas Projects during the days of the symposium, while the artist duo Varvara and Mar brought their newly developed 3D sculptures and prints to Alalimón Gallery and Mario Santamaria presented his explorations of networks in a solo exhibition at Àngels Barcelona. All three solo shows combined screen-based artworks with prints and, in some cases, sculptures, which points to a telling flexibility of formats that seamlessly move between the physical and the virtual.

These last examples provide an explanation to the rich variety of approaches to new media art that can be seen in the three exhibitions currently on view in Barcelona. Not only due to the curator’s visions and decisions, the plurality of forms of artistic projects related to science and technology is caused by the artists’ own interest in moving away from a strictly “new media” aesthetic that has been so common in festivals and specialized events and exploring a culture that is already immersed in the digital and does not always require complex technological devices. Our daily life incorporates the experience of virtual environments, artificial intelligence, and interactivity, and is routinely affected by algorithms. This means that the possible spaces for new media art are expanding to the point where distinctions are no longer necessary: everything is, and has always been, art.