Pau Waelder

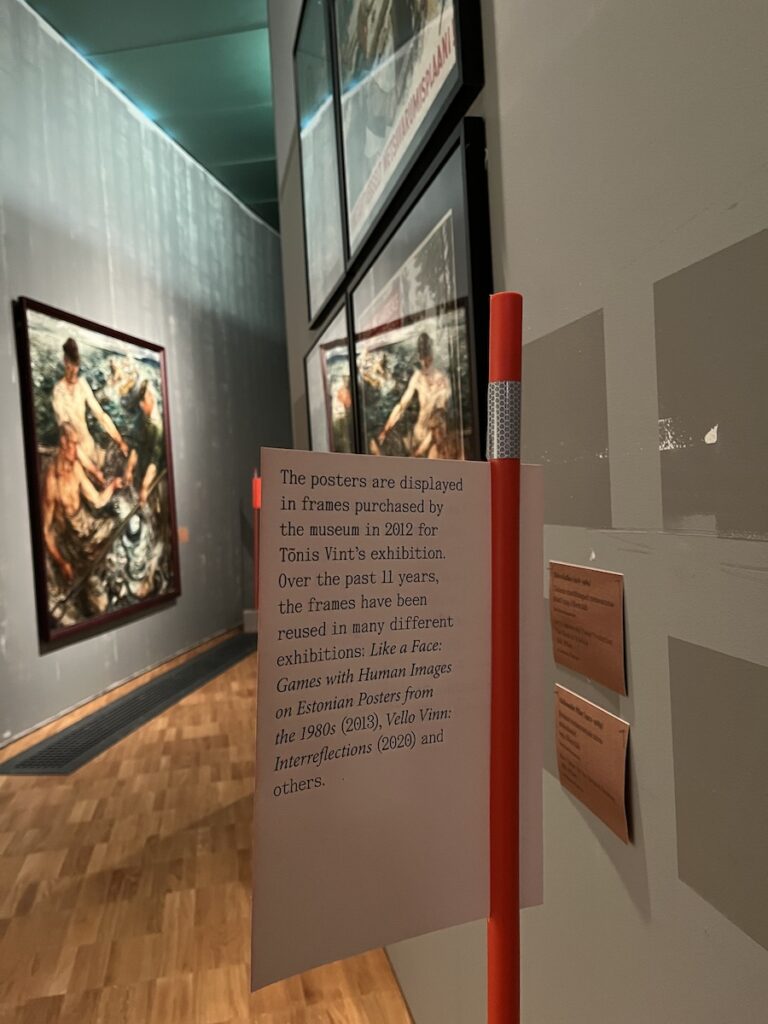

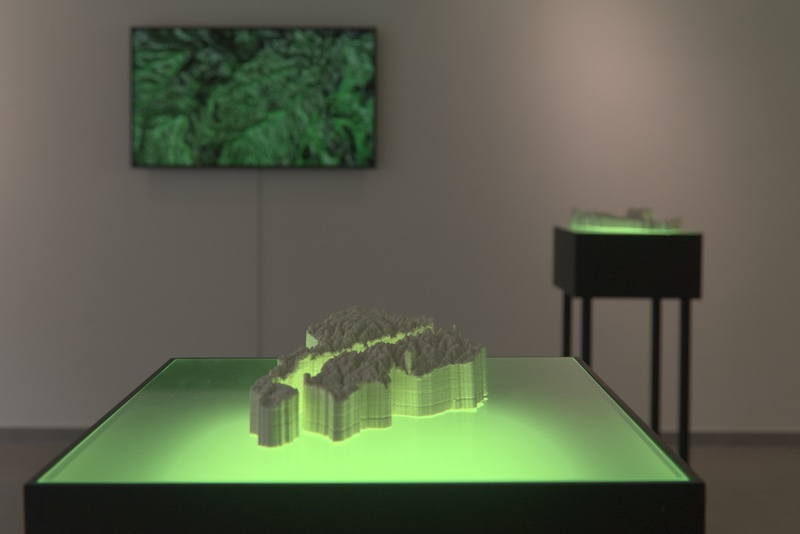

Laura Colmenares Guerra. Fracking Island #3, 2023

Over the last two decades, Brussels-based Colombian artist Laura Colmenares Guerra has carried out a consistent body of work in the form of interactive audiovisual installations and live performances. Her work is characterized by a research-based practice that requires long processes and interdisciplinary collaborations, focusing on the difficult relationship between our industrialized societies and the living ecosystems we are a part of. Since 2018, Laura is engaged in a series of artworks exploring the environmental impact of neo-liberal extractivist practices in the Amazon basin.

Niio is proud to present a series of videos from this recent work, that illustrate her conceptual and aesthetic approach to this subject. In this exclusive interview, the artist elaborates on the production of the Rios Trilogy and the key elements of her artistic practice.

Explore Lagunas by Laura Colmenares Guerra, a narrative around the environmental consequences of hydraulic fracturing.

In your work, one finds a growing interest in the concept of landscape, from a more general or abstract perspective, to the specific region of the Amazon basin. Can you elaborate on your interest in landscape as a concept? Has the change of landscape from Bogotá to Brussels contributed to your ongoing reflection?

The concept of landscape holds a pivotal position in both my research and artistic practice. My master’s thesis was dedicated to the exploration of landscapes within video games, and ever since, the notion of landscape as a means of structuring our perception of the world has remained a constant presence.

“Western societies’ relationship with nature is characterized by distance and objectification.”

The concept of “landscape” finds its origins in the Dutch term “landschap.” The etymology of the word “landscape” can be traced back to the 16th century when it was used to describe paintings depicting rural scenery, defined as a “painting representing an extensive view of natural scenery”. This meaning occurs at a time when distance observation from a fixed and dominant position is the symbolic form by which reality (perspective) is measured. Perspective allowed the modern individual to become a contemplative observer, establishing a distinct separation between the subject and the object observed from a distance. This conscious acknowledgement of distance transformed the relationship with the environment into a reflective and contemplative one. It implies the need for a conceptual apparatus, category diagrams, and concepts that make this experience possible. This dual perspective, characterized by both distance and objectification, fundamentally shapes Western societies’ relationship with nature.

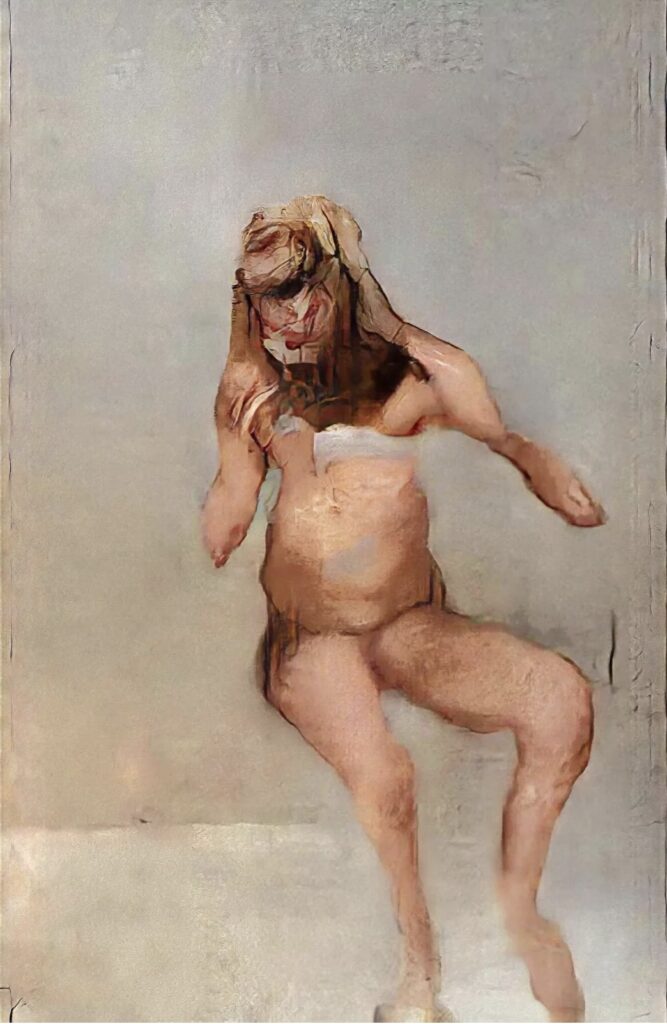

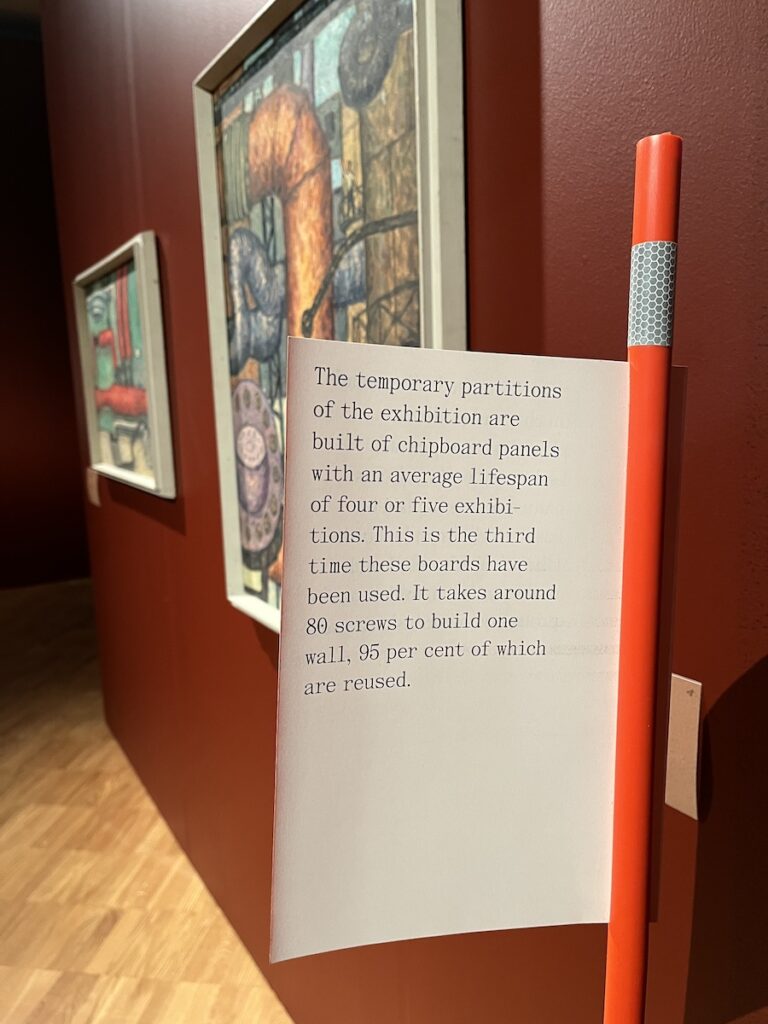

Laura Colmenares Guerra. Fracking Island #4, 2023

A certain tension or equilibrium between control and spontaneity can be found in your work, for instance in the use of cartography, data analysis, and 3D scans as a form of capturing the landscape, as opposed to introducing audience participation or creating live performances where there is more room for the unscripted. How do you feel about the notion of control, particularly in relation to our environment and the natural systems around us?

My work involves a range of processes, transitioning from analysis, tools and methodologies from other disciplines to more speculative and experimental procedures. I enjoy being in control as much as I enjoy surrendering it. As a result, my creations often exhibit multiple layers, occasionally presenting significant contradictions.

“My goal is to provoke questions rather than provide answers”

For example, in Chapter N.2 of the Ríos Trilogy, I fragment the territory of the Amazon Basin with hydrological parameters. Yet, I know that the fragmentation of ecosystems is one of the key problems when preserving the connectivity between biomes. I prefer to maintain a sense of ambiguity, allowing the viewer to approach my work from various perspectives. My goal is to provoke questions rather than provide answers. Likewise, when I grant control to the audience, I willingly surrender it myself. This aspect of my creative process is deeply intriguing to me.

You carry out your artistic projects through long term processes of creation and transdisciplinary collaborations. Can you briefly walk us through the main phases in one of your projects, the time frame, and comment on how these collaborations arise and develop?

I enjoy writing, even though it can be extremely painful; it’s essential to my work. I’ve never published, but I have a collection of texts that I write through the creation process of each piece. I keep track of all the versions as a way to keep track of the ideas and strategies that lead me to give a specific form to the work. Most of the time, I start from a basic or simple concept. In the case of the Rios Trilogy, it all started from the #AmazonFires. The day I started researching this hashtag, I would have never imagined that I would be engaged with this research for five years (and counting). Now finished, the Ríos Trilogy seems like a solid three-chapter project, but when I started, I was not sure what would be the final output.

“Experimenting implies pushing the limits of media or techniques, so I always have to make sure I work with experts who feel comfortable engaging in experimental methodologies.”

Once I feel a concept is solid enough, I decide to give direction to it and see how to make it evolve into an artwork. Often, the next phase implies finding experts in the field to start grounding the ideas into possible outcomes. That process includes budgeting and finding subsidies to pay the people involved in the project, to pay myself and to find the money to realize the ideas. I define objectives, yet I generate a framework in which the process can permeate the outcome. Collaborating with people from different fields is extremely interesting. The process always includes experimentation; often, many failures happen before the final pieces come to life. For both the experts I collaborate with and for myself, experimenting implies pushing the limits of media or techniques, so I always have to make sure I work with experts who feel comfortable engaging in experimental methodologies.

I often spend more time than I’d like dealing with administrative and production tasks, which can be frustrating. I sometimes have to hire people to do part of the work, but I also give myself enough time to do aspects of the work that I don’t want to delegate. For example, the porcelain 3D printed sculptures of Chapter N.2 of the Ríos Trilogy. I took pottery lessons for over a year while, in parallel, experimenting with the 3D printer in my studio. It took me around two years to achieve the results I had in mind. Many failures and doubts often accompany the process. Still, it is extremely satisfactory when you start having good results, and suddenly, you look back and see how much skills and knowledge you’ve learned in the process.

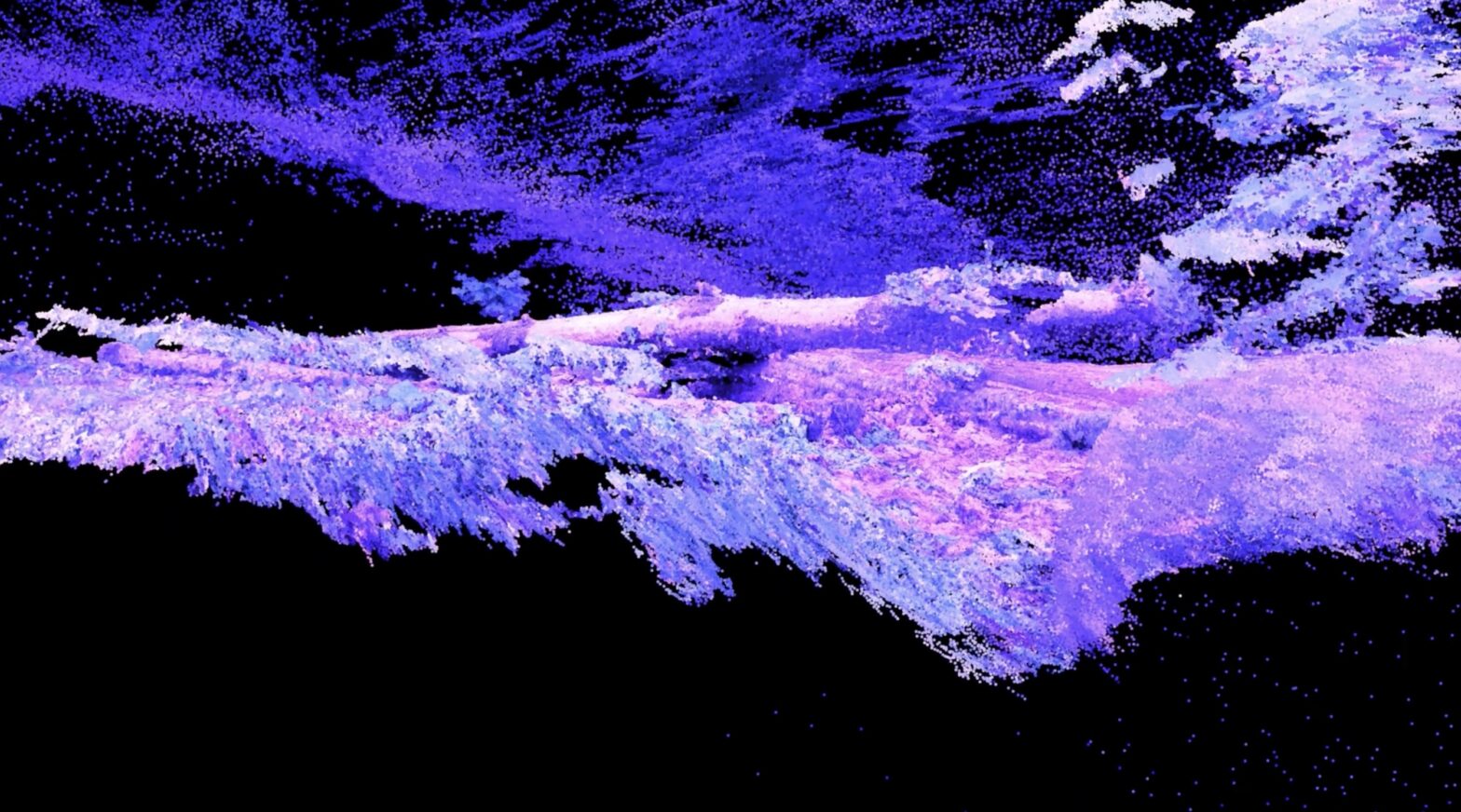

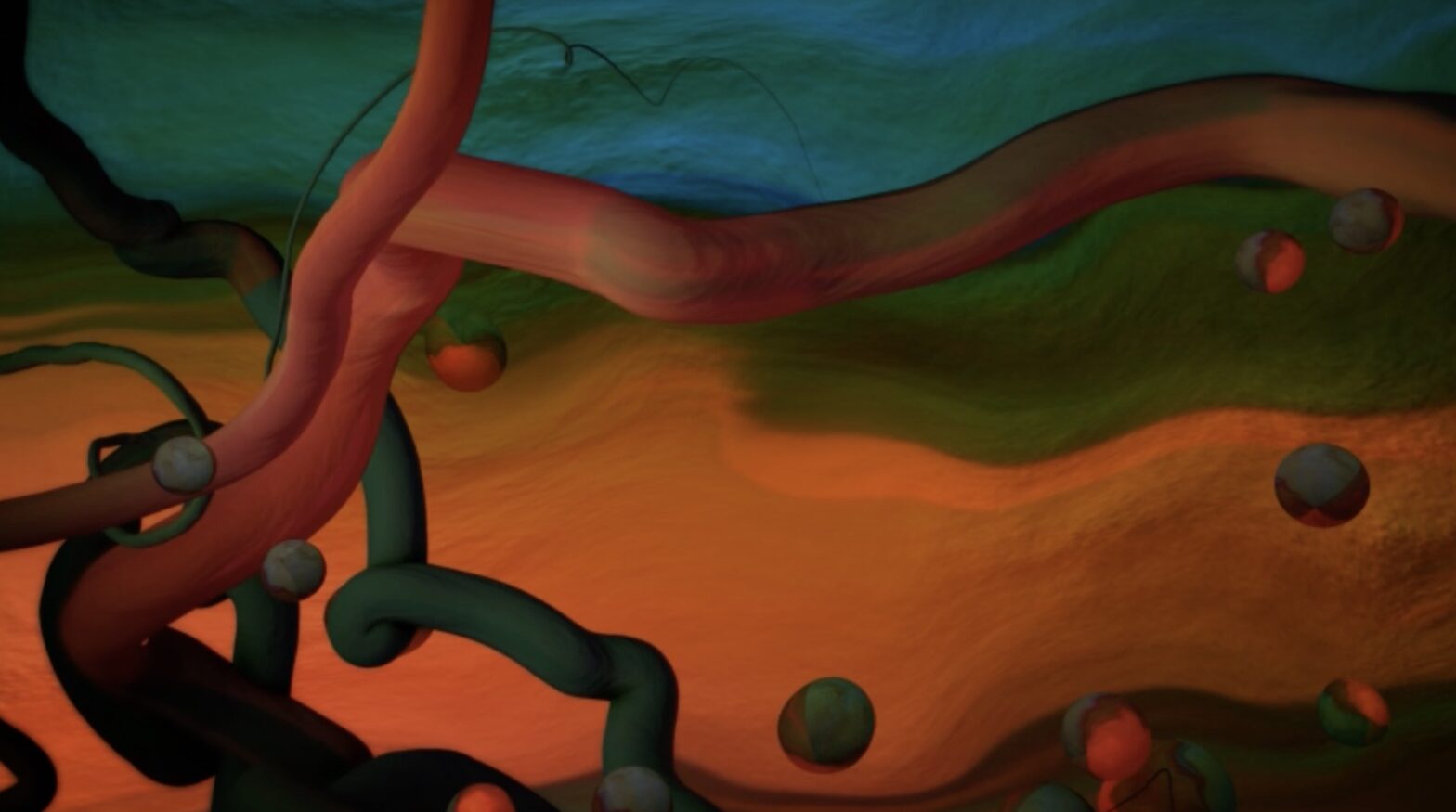

Laura Colmenares Guerra. Fracking Island #5, 2023

You also work as a VJ and have collaborated in numerous live audiovisual performances. How does your experience in this field inform your installations and videos in terms of the process, dynamics, and aesthetics? What is the role of sound and music in your work?

Sound and music have consistently held a central position in my works, although it’s only recently that I fully embraced this passion. Throughout my journey, I’ve collaborated with musicians, composers, and record labels, yet I never quite ventured into creating music myself. However, in 2023, I decided to delve into this realm independently. Techno music has been a steadfast companion throughout my life. It was my gateway into VJing in the past. This year, I made the leap into DJing and have been sharing this passion with my son, as we’ve spent the last few months mixing together. We’re preparing for a duo project set to be released in 2024. Simultaneously, I’ve been quietly immersing myself in the study of electronic music production; I might share some of my own compositions with the public in the coming months.

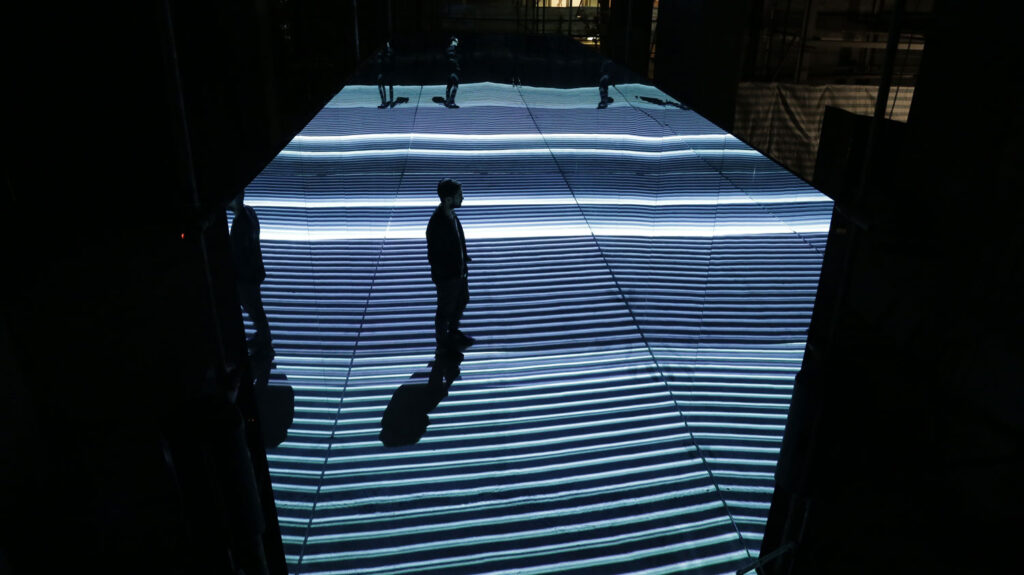

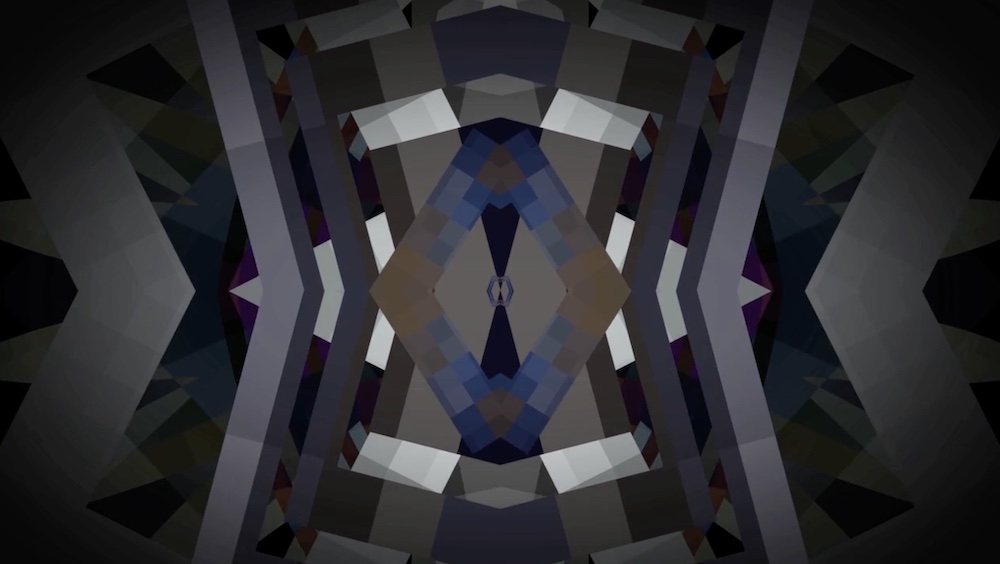

Laura Colmenares Guerra. Variations of Dissaray, 2016

Your work involves both installation and video as well as sculpture and VR environments. What drives you to choose one format/technique over another for each project? In the Ríos Trilogy, for instance, we find data visualization and analysis as well as 3D printed sculptures and a VR environment; how do they complement each other?

I consider myself an idea-based artist rather than a medium-based artist. That means that even though installation is a constant in my work, the components included in the installation work are subject to change from one piece to another. My main creation tool is 3D, but 3D can be used in many ways, from printing to VR, animation, still images, augmented reality, etc. I like combining techniques and tend to incorporate material and non-material elements. Each media has its language. I explore paths to generate dialogues between different media.

“I consider myself an idea-based artist rather than a medium-based artist. My main creation tool is 3D, but 3D can be used in many ways, from printing to VR, animation, still images, augmented reality, etc.”

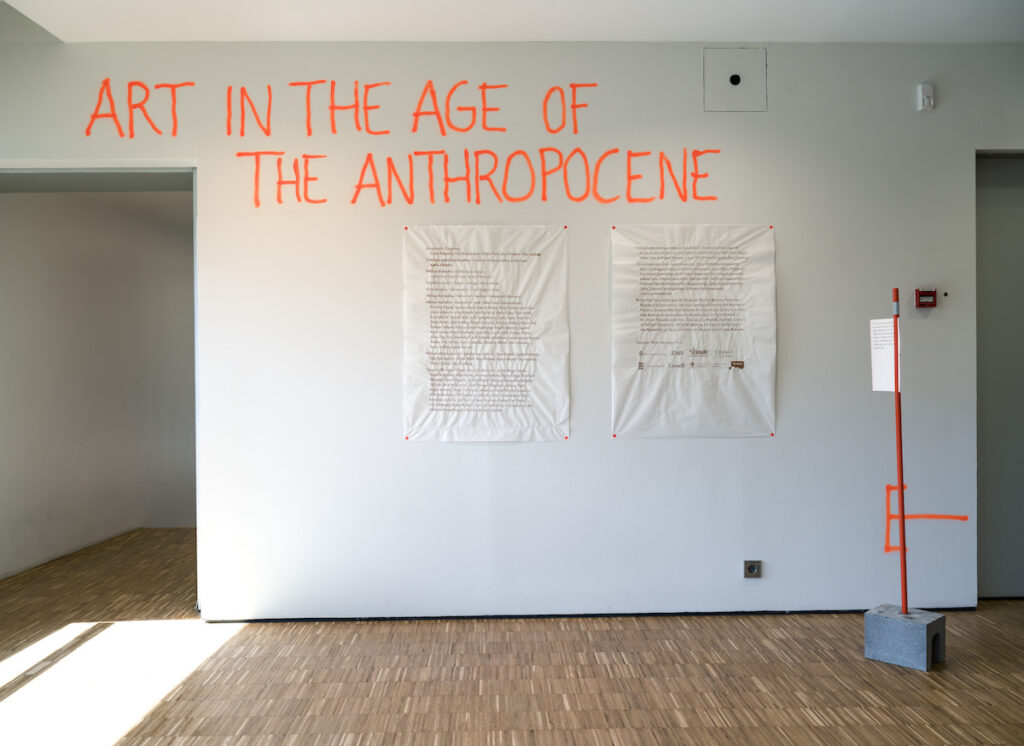

Laura Colmenares Guerra. Fracking Island #1, 2023

As a Colombian, I imagine that you feel a closer connection to the exploitation of natural resources in the Amazon basin in neighboring Brazil. How do you see the societies in the Northern Hemisphere, and particularly European societies, react to this issue? Do they see it as a remote problem? Does your work aim to bridge this gap of awareness?

The glaring disparity between the Northern and Southern hemispheres evokes strong emotions in me. I am profoundly critical and sensitive when it comes to this issue. Growing up in Colombia, a country tormented by civil war and influenced by the United States in its perpetuation, I realized at a young age that in the realm of geopolitics, the wealth of some often rests upon the suffering of others. I adopt a critical perspective towards European politics, despite the veneer of democracy; beneath the surface lies the pervasive corruption of democratic processes, fueled by ruthless corporate lobbying. What Indian activist Vandana Shiva aptly identifies as ‘the corporate control of life’ is responsible for the spread of neoliberal globalization, international trade policies, unchecked environmental exploitation, the privatization of natural resources, and the patenting of biological material. I undoubtedly address these problems through my work.

“Despite the veneer of democracy in European politics, beneath the surface lies the pervasive corruption of democratic processes, fueled by ruthless corporate lobbying.”

Lagunas addresses the issue of fracking within the different extractive practices that currently poison the natural environment. Within the context of your ongoing exploration of the landscape, why did you choose fracking as a subject? Why did you choose the Chingaza Natural National Park in Colombia as a source of some of the images in this project?

Burning fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas) represents the primary driver of global climate change, responsible for more than 75% of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 90% of carbon dioxide emissions.

As we approach the shortage of conventionally accessible fossil fuel reserves, hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as fracking, has gained greater prevalence. Fracking entails fracturing reservoir rocks by injecting toxic fluids at high pressure and keeping the split (the fracture) open by placing sand or similar in it. This process carries significant environmental repercussions; one of them is the contamination of the water sources in the subsoil of the Earth. In addition to the already evident pollution of the atmosphere, we must weigh the duration of fossil fuel extraction and our readiness to confront the consequences of polluting underground water sources on Earth.

“We must weigh the duration of fossil fuel extraction and our readiness to confront the consequences of polluting underground water sources on Earth.”

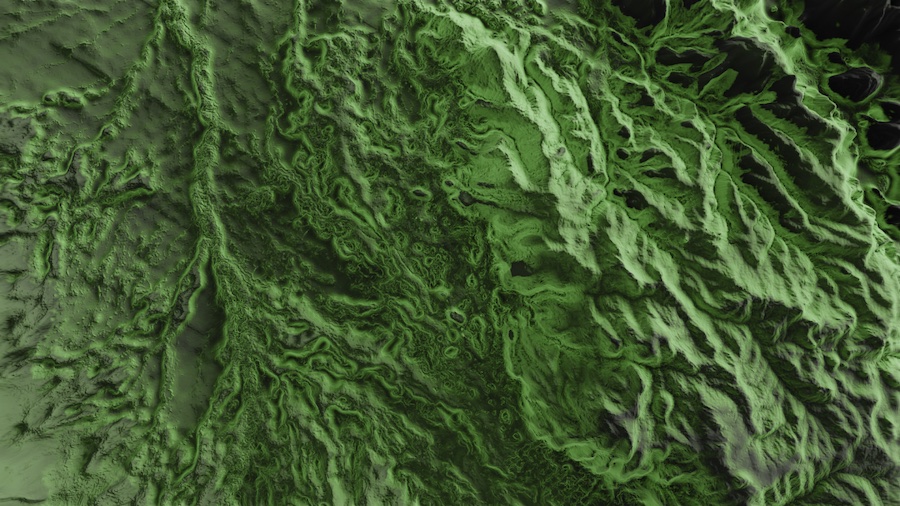

Lagunas delves into themes of water contamination, water scarcity, death, and memory. These concepts interweave within an interactive scenario featuring computer-generated imagery (CGI) combined with onsite images captured at Chingaza Natural National Park in Colombia, as well as underwater footage. Through these landscapes, I aimed to create an atmosphere that evokes both prehistoric and futuristic elements.

I selected Chingaza Natural National Park as the backdrop for this project due to the unique characteristics of its ecosystem, known as ‘Páramo’ in Spanish (for which there is no precise English translation). ‘Páramos’ are ‘Neotropical’ high mountain biomes in South America. They are primarily characterized by the presence of giant rosette plants, shrubs, and grasses. These giant rosette plants play a crucial role in capturing atmospheric water, which then travels through the soil, accumulates, and nourishes underground water systems. ‘Páramos’ ecosystems hold immense significance, notably in the formation of the rivers that comprise the intricate water network of the Amazon Basin.

Laura Colmenares Guerra. Fracking Island #6, 2016

You state that the interaction between the audience and the installation aims to create a direct implication of the viewer in the processes that are described in this piece. Can you explain the type of interaction you chose and how it creates this implication?

When I incorporate interactive elements into an installation, I seek out devices or objects that I can modify/hack to serve as interfaces for the audience. These interactive devices are chosen based on the potential of mediating the experience for the visitors. Such is the case of Lagunas, in which I created an interactive interface by hacking water industrial valves with optical sensors. The spectators interact with these valves, which recall the gesture of opening the water tab, as well as that of operating a steering wheel.

You filmed the landscapes of Lagunas in Chingaza and have also participated in an art program at the Brazilian Amazon, from which emerged Ecdysis and the Ríos Trilogy. How was your experience of working on site and the collaborations that emerged for these projects?

I enjoy working onsite. Immersing myself in the very landscapes I’ve researched from behind a computer screen enriches my perspective significantly. What I find most rewarding, though, are the human connections forged during these journeys.

“In the upcoming month, I will embark on a new project centered around the chanting traditions of the Amazon People.”

In the upcoming month, I have an exciting journey planned to the Amazon, where I will embark on a new project centered around the chanting traditions of the Amazon People. Collaborating closely with the indigenous communities, we will explore sound and experiment with various methods of visualizing sound frequencies. It’s the first time I’ll work directly with communities, and I look forward to having a direct dialogue with the guardians of such an amazing and important territory.