Pau Waelder

More than a year ago, NFTs burst into mainstream contemporary art through the spectacular sales that took place in Christie’s and Sotheby’s, leading to a market frenzy and the emergence of numerous marketplaces and record selling NFT drops. At the time, most of the art world had to quickly figure out what an NFT is, how the blockchain works, and ultimately try to understand why NFTs were reaching such astronomical sums. Nowadays, when the contemporary art market is finally integrating limited edition digital artworks minted in a blockchain as another type of art offered for sale in art galleries and art fairs, the pertinent question is no longer what is an NFT, but why is it an NFT, why did the artist choose to attach a non-fungible token to her artwork and what does that bring to the concept and the nature of the piece.

The answer to this question is not always “to make more money,” even though it is obvious that the NFT market has been driven by the promise of enormous profits laid out by the initial auction sales, and that the conversation around NFTs tends to revolve around sales figures rather than what the artworks are about. Following an invitation to give a keynote speech at the NFT BCN 2022 event in Barcelona, I decided to address some of the reasons why artists create NFTs, based on recent observations and an exploration of the developments in the art market and digital art over the last two decades.

What is new or different about NFTs?

To begin, it is worth considering what minting a digital artwork as a non-fungible token entails, how is it different from selling the artwork in a USB stick, as a print, or as a physical object including a customized screen and computer. This brings us to the perennial question: What is an NFT?

Explanations vary in complexity and detail, but to keep it simple let’s start by saying that an NFT is a blockchain-based proof of purchase. The token itself is a register on the distributed, tamper-proof ledger that is a blockchain (yes, “a” blockchain and not “the” blockchain, as there are many different blockchains out there). Most commonly, the token includes a link to a distributed file system, such as IPFS, where the artwork file is located. Therefore, the NFT does not contain the artwork, it is linked to the artwork and contains information about who owns it (exceptions apply, see below).

To summarize, in most cases a digital artwork minted as an NFT is stored online and is publicly accessible (and downloadable), but can only be officially owned by whoever owns the token associated with it.

This simple description usually prompts another perennial question: Why pay for an artwork that is available online? While this question is worth another article, let’s focus this time on the aspects of a digital artwork minted as an NFT that make it more than just an image or a video that anyone can download:

1. An NFT, as discussed, certifies the ownership of a digital artwork in a way that is publicly verifiable. This is quite significant as, up until recently, artists could only provide a signed piece of paper and maybe an engraved hard drive, DVD, or USB stick to give collectors a proof of ownership of the artwork.

2. The ownership of a non-fungible token can be easily transferred, which facilitates the exchange of artworks in a secondary market. Yes, in the accelerated, frenzied market around NFTs this has frequently translated into speculative practices and lightning-fast art flipping, but it is not always bad that an artwork changes hands, and in these operations the artist can benefit (see below).

3. Buying an NFT can unlock other content (higher resolution images or videos, access to other artworks, additional formats, and so forth) that bring considerable extras to the “image-that-anyone-can-download” and can lead to a particular relationship between collector and artwork.

4. In some cases, the NFT can contain the artwork, or part of it. On-chain NFTs include the code that generates the artwork inside the token, or else a specific part of the code that can run in an external program. An example can be found in the series Autoglyphs by Larva Labs, the first on-chain generative art to be minted on the Ethereum blockchain.

5. Finally, NFTs contain smart contracts, which execute specific actions automatically when certain conditions are met. The most common is to include artist royalties on every sale in the secondary market. When an NFT is sold to a new collector, the smart contract ensures that the monetary transaction is split between the previous collector and the artist, according to a predefined percentage, each amount being automatically transferred to their respective wallets. Smart contracts can do much more, but we’ll see that later.

These features of NFTs already point to possible answers to the question “why is it an NFT?,” but let’s explore further why artists are creating NFTs on the basis of four key motivations.

Reaching a larger audience

An artwork, by definition, needs an audience (at least, per George Dickie’s useful but controversial circular definition of art). Artists usually want to reach as large an audience as possible, as gaining popularity contributes to legitimize their position, but also because they want people, lots of people, and not just wealthy collectors, to enjoy their art. Artists wanting to make their art more affordable have usually resorted to multiples, that is artworks created in large editions that are sold at smaller prices. A well known example is the initiative created in 1959 by artists Daniel Spoerri and Karl Gerstner, MAT (Multiplication d’Art Transformable), which produced multiples by different artists in editions of 100 copies at $50 each. All multiples, regardless of the reputation and market value of the artist, were sold in the same amount of copies and at the same price.

This leveling of art market hierarchies and the conception of the artwork as a massively produced merchandise set the bases for what is usually referred to as the “democratization of art.” The 1960s and 1970s saw the full development of the consumer society and it is not surprising that artists reacted to the Zeitgeist by conceiving ways of turning their artworks into mass consumer products, particularly Pop artists like Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol, in landmark shows such as The Store in 1961 or American Supermarket in 1964. Later on, it would be artists connected to graffiti and street art who would embrace this idea, as exemplified by Keith Haring’s influential Pop Shop (1986-2005), and lately by artists Shepard Fairey, KAWS, and Bansky, among others.

The NFT market is currently bringing together two types of artists who are particularly interested in reaching a larger audience: artists who work with digital technologies and artists whose work is located on the fringes of the art market or the art world. The former have found themselves creating digital art and usually receiving little attention outside of a circuit of specialized festivals, exhibitions and galleries. Now suddenly, there is widespread attention for digital art, but focused on NFTs, which also promise substantial gains. The latter have experienced a similar situation, although their work was either not digital (street artists, mainly) or not considered fine art (illustrators, SFX creators).

Therefore, the NFT market is currently fed by the creations of digital artists who either directly mint their work on a blockchain or adapt it to the format in which NFTs are sold. In doing so, they reach a potentially larger audience, not only because the artworks are available online, but also because they are sold in the context of a growing community and are frequently available at very affordable prices.

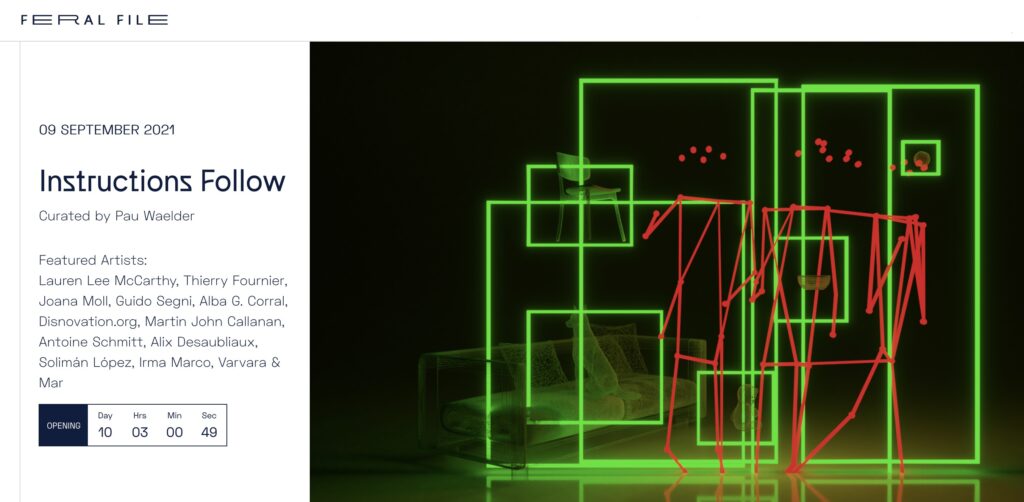

Take for instance, Feral File, an online exhibition space, marketplace, and community for digital art created in 2021 by artist Casey Reas and the team at Bitmark. The platform launched with a series of curated exhibitions of up to twelve artworks by different artists. In each exhibition, the price and edition size is the same for all the artworks, in a similar way to how Spoerri and Gerstner conceived MAT. The first exhibitions put the artworks for sale, on average, in editions of 75 at $75 each. The intention was clearly to make digital art accessible to a large audience and popularize it, although the enormous success of Feral File led to the editions frequently being sold out merely seconds after the sale and then circulating in the secondary market, a situation that ironically had already happened in the 1960s with the editions of MAT.

Another telling example is Hic et Nunc, an NFT marketplace on the Tezos blockchain launched in 2021, which quickly attracted the attention of artists due to its open structure and the low cost of minting on Tezos, a cryptocurrency with a much lower value than Ethereum. Hic et Nunc (also known as HEN) nurtured a large community of digital artists who produced and bought NFTs from each other, usually at very low prices (ranging from $1 to $20). In September 2021 it was discontinued by its founder, but it has mutated into a number of mirror sites and other initiatives, such as Objkt, TEIA, or AlterHEN, which continue to offer eco-friendly NFTs at relatively affordable prices.

A standard protocol for selling digital art

Artists working with digital technologies have long sought solutions to sell their artworks, particularly online, without any physical object attached to them. Since the early days of net art, when artists started exploring the possibilities of creating artworks specifically for the World Wide Web, it seemed that they could only put their work out there for everyone to see, for free. Pioneering artist Olia Lialina turned her website into a net art gallery in 1998 and simply offered the works for sale. She sold one to the artist duo Auriea Harvey and Michael Samyn and sent them the files so they could host the artwork in their own server. Other artists have tried different approaches.

For instance, in 2002 artist Mark Napier created The Waiting Room, an online shared space for multiple users that was offered to collectors in the form of 50 shares, sold through the bitforms gallery. Later, artist Rafael Rozendaal famously came up with the idea of creating online artworks as websites with their own domain name, and developed an “Art Website Sales Contract” to ensure that collectors would keep the artworks online and linked to their corresponding domain names.

These and many other initiatives were aimed at creating scarcity for an endlessly reproducible artwork and to provide collectors with a publicly verifiable proof of ownership. However, each solution was conceived for specific artwork and did not constitute a general model that could be applied to any digital artwork. Furthermore, since every solution was more or less unique, it had to be explained to collectors, who saw themselves as explorers of an unknown territory, acquiring a work of art in a format with newly invented rules.

Around the beginning of the 2010s, content platforms and art marketplaces for web and mobile began to emerge, and artists saw in them a possible solution for the dissemination of their works among a larger audience. In 2009, artist Jonah Brucker-Cohen published in Rhizome a series of articles in which he described the possibilities of selling digital art through Apple’s App Store, at a time when the revolutionizing influence of the iPhone (released in 2007) was starting to be felt:

“ Instead of giving away your work for free on the web, Apple’s iPhone and iTouch devices provide an ample platform for distribution (through the Apple App Store) and hardware support for novel ways to experience screen-based work.

[…] Since Apple has kept the economic barriers for entry into this world of mobile development relatively low, it’s easier than ever for artists to use these devices for their creations and have an instant audience of millions to enjoy them.”

Jonah Brucker-Cohen, “Art In Your Pocket: iPhone and iPod Touch App Art” Rhizome, July 7th, 2009

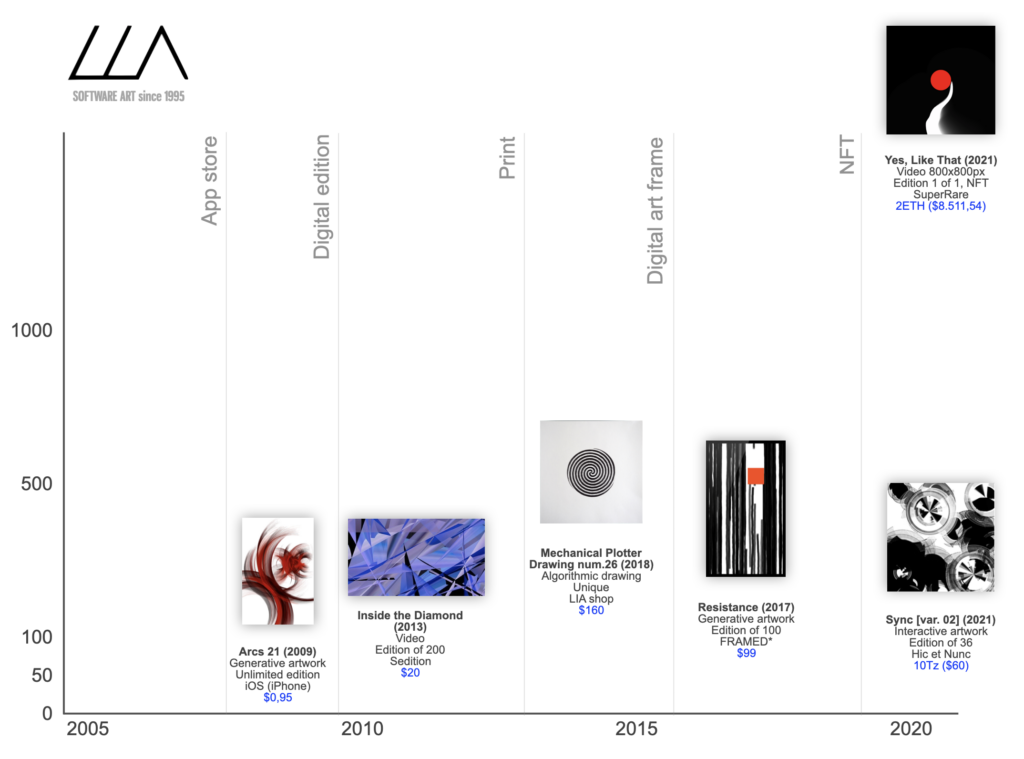

Many artists who worked with code started turning their artworks into apps and offering them for low prices, in the range of other apps on the App Store, which at the time were sold at $1- $5. Among them the software art pioneer LIA stands out as one of the artists who has developed the widest variety of formats to distribute her art online. In 2009, she launched her celebrated generative artwork Arcs 21 as an iPhone app.

A few years later, she joined the platform Sedition, creating a series of digital editions from video excerpts of her generative works. At the same time, she opened an online store on her own website (à la Olia Lialina) and started selling plotter drawings and prints. By the end of the decade, she had also presented her work in the digital art frame FRAMED*, a device composed of a screen and an integrated computer that includes its own selection of artworks in limited editions.

In 2021, the NFT boom caught LIA well prepared to respond to this new protocol for selling digital art. Given her reputation, she was quickly invited to join curated NFT marketplaces, where her work has reached considerably high prices. But at the same time, she has experimented with lower priced artworks on Hic et Nunc, creating interactive and generative pieces in large editions. Her distributed presence in the NFT market exemplifies how some artists with an established professional trajectory in the digital art world have found in non-fungible tokens a way to sell their art to different audiences, testing different formats, edition sizes, and prices.

It can be said that NFTs bring a solution (not the solution, as it probably does not exist) to selling digital art online to a wide audience by establishing a common protocol that allows for variations but is widely known and accepted, and furthermore validated on the highest level of the art market hierarchy by the auctions that took place at Christie’s and Sotheby’s.

Collecting a work-in-progress

For digital artists, an artwork would normally go to the art market when it was tried and true, if it was based on software, or in a format that collectors could trust, such as a print or a video (the latter still raising many doubts). Experimentation would happen at the studio, in an artist-in-residence program, or sometimes at an exhibition or a festival. Experiments could also be distributed online, for fans and fellow artists to experience at their own risk, for free.

Nowadays, NFTs offer the possibility of minting and selling an experimental piece of software art and letting adventurous collectors purchase a copy to support their practice and be among the first to experience the artwork. During 2021, Hic et Nunc became the optimal environment for this type of experimentation, which was supported by a strongly motivated community and the fact that the artworks themselves were sold for very low prices.

One example is Kim Asendorf’s The Insane Collectors (2021), an artwork consisting of the visualization of the names or wallet addresses of those who bought one of its 110 editions.The piece is a program that took its data from an API of an external source, and therefore the artist warned that it could stop working the moment there were changes on this API, as it did happen in September 2021 when Hic et Nunc was discontinued. While the piece continues to be available on the marketplace Objkt, it has ceased to work and belongs, conceptually and procedurally, to its previous existence on HEN. For those of us who bought an edition, it meant spending a mere 5 TEZ (around $20), supporting the artist’s crazy idea and being part of something that, in my opinion, was interesting.

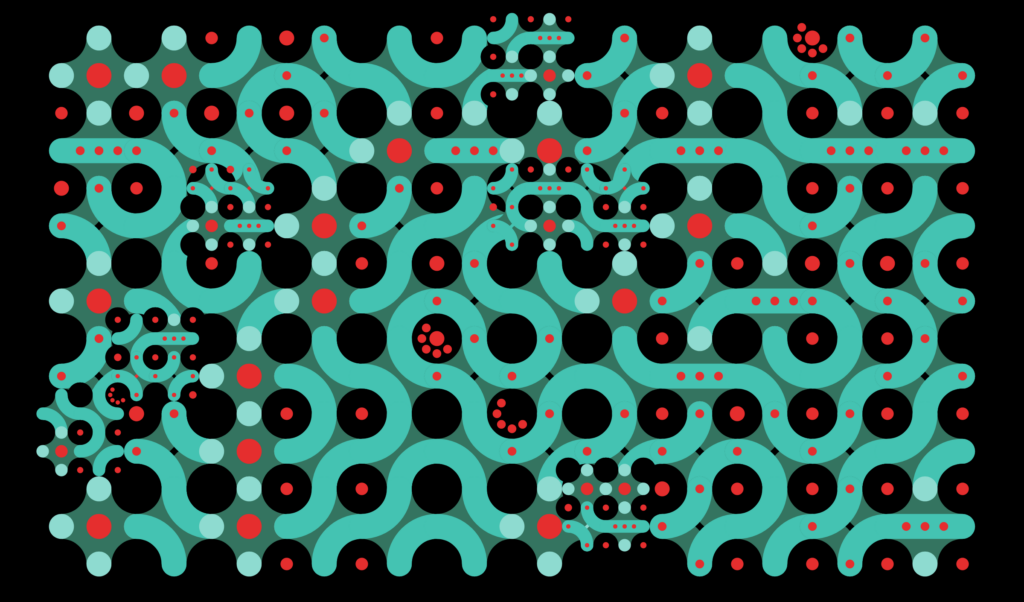

Collecting in the NFT marketplace has often been seen as led by speculation and profit, but there is a lot of genuine interest in the artworks and a willingness to trust and support artists. In particular, the current form of selling generative artworks as NFTs speak of this involvement of collectors. On ArtBlocks and other marketplaces, generative artworks are sold in large editions by setting up a program that creates a different composition every time it is minted, until reaching, for instance, its 1,000th creation. The series is then completed, each artwork being unique but at the same time a variation of a single compositional style.

When collectors mint their edition, they do not know how the resulting artwork will look like, only that it will be in line with the aesthetics defined by the program. This is actually similar to how some collectibles are sold in opaque envelopes and boxes, and just in the same way many collectors head to the secondary market to exchange the composition they got for the one they like.

Smart contracts: the ghost in the machine

Finally, a compelling reason to mint a digital artwork as an NFT is to explore the possibilities of smart contracts. As previously mentioned, smart contracts automatically enact instructions previously established by the artist when certain conditions are met. The applications of this technology are potentially endless, and it is up to the artists’ creativity to find interesting ways of embedding these instructions into their artworks.

Jonas Lund, an artist who has frequently played with auto referentiality and the systems of the art market, famously elaborated his own analog “smart contracts” in a series of paintings titled Strings Attached (2015), in which the canvas displayed a text indicating a string of conditions linked to the purchase of the artwork. He has later brought this idea to non-fungible tokens in the series Smart Burn Contracts (2021), consisting of contracts that the owner of the NFT must comply to, and provide proof of compliance to the artist, who will otherwise burn the token and destroy the artwork. While here the artist takes on the role of verification that would be carried out by a program, it conceptually links to the possibilities provided by this technology.

Other artists are using smart contracts to determine the development of an artwork over time and establish particular relationships between the collector and the artwork.

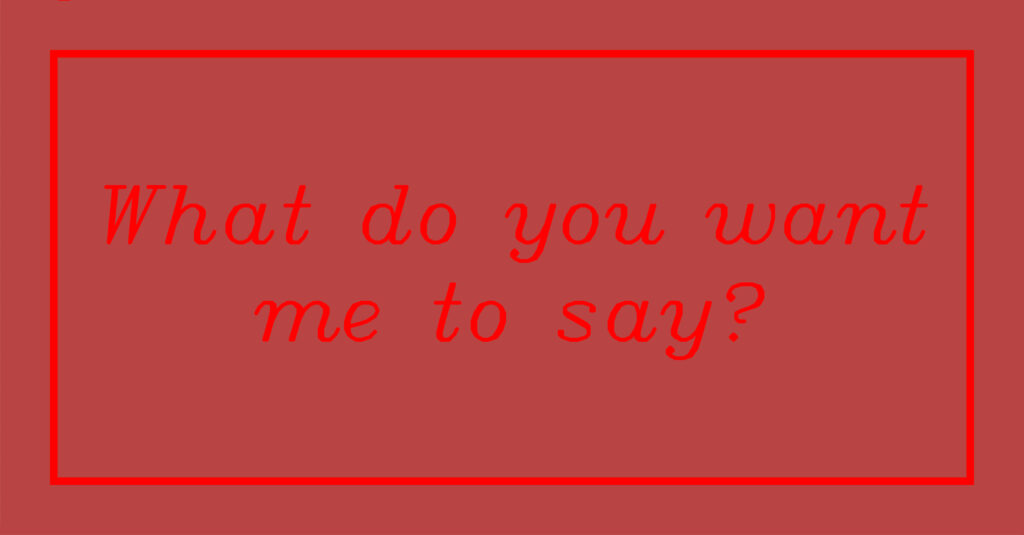

Lauren Lee McCarthy created What Do You Want Me To Say?, an interactive artwork, for an online exhibition at Feral File that I curated in 2021. The artwork, which was offered in an edition of 75 and minted as an NFT, consisted of a program that enabled users to interact with the synthesized voice of the artist. The voice asked the user “What do you want me to say?,” collected the user’s reply via the computer’s microphone and then repeated the sentence using the artist’s voice. A reflection on the ways in which female–voiced digital assistants normalize the notion of addressing women in imperatives, the artwork was open to interaction with any user during the first month of the exhibition, and then was only available to collectors, until, a year after its first release, it will remain as an archive of past interactions.

Exploring the relationship between collector and artwork, artist Sara Friend has recently created Life Forms (2021), a series of NFT-based digital entities that require collectors to transfer their ownership to other collectors (or wallets) every 90 days in order to “keep them alive.” The artwork plays with the notion of ownership and the practice of art flipping in the NFT market, while inviting collectors to participate in a sort of ongoing ritual or competition in which it remains to be seen who will be able to keep their NFT for longer. Obviously, many collectors simply switch the NFT between two wallets, but still by doing so they participate in the process devised by the artist.

This brief exploration of the reasons why artists mint their digital artworks as NFTs provide an initial approach to the possibilities offered by this blockchain-based proof of purchase, which in the hands of creative individuals can become a powerful tool for the development, dissemination and collecting of digital art.