Pau Waelder

It is hard to find information about Daïchi Mori, an elusive artist who, despite being active on Twitter and Instagram, does not like to talk about himself. His work consists mainly of drawings on paper inspired by traditional Japanese art, but with a personal twist that connects with contemporary manga and pop culture.

A collaboration with Nieto, a French-Colombian filmmaker, performer and stage director with a penchant for the grotesque and surreal, has brought his work out of its secluded world. Nieto’s three-part documentary film, aptly titled Daichi Mori. The Art of Unexisting (2021), portrays him as a hikikomori, a person who has decided to avoid all social life, in a manner that is both humorous and mythicising, playfully addressing the archetype of the mysterious, secluded artist.

Interested in disseminating his work in editions of NFTs, Mori has created a series of animations based on the main subjects of his drawings, some of which are presented in the artcast Hikigaeru. Entering the NFT scene has brought Mori in contact with other artists, among them Mihai Grecu, who kindly facilitated the initial contact that led to the collaboration with Niio and to this interview.

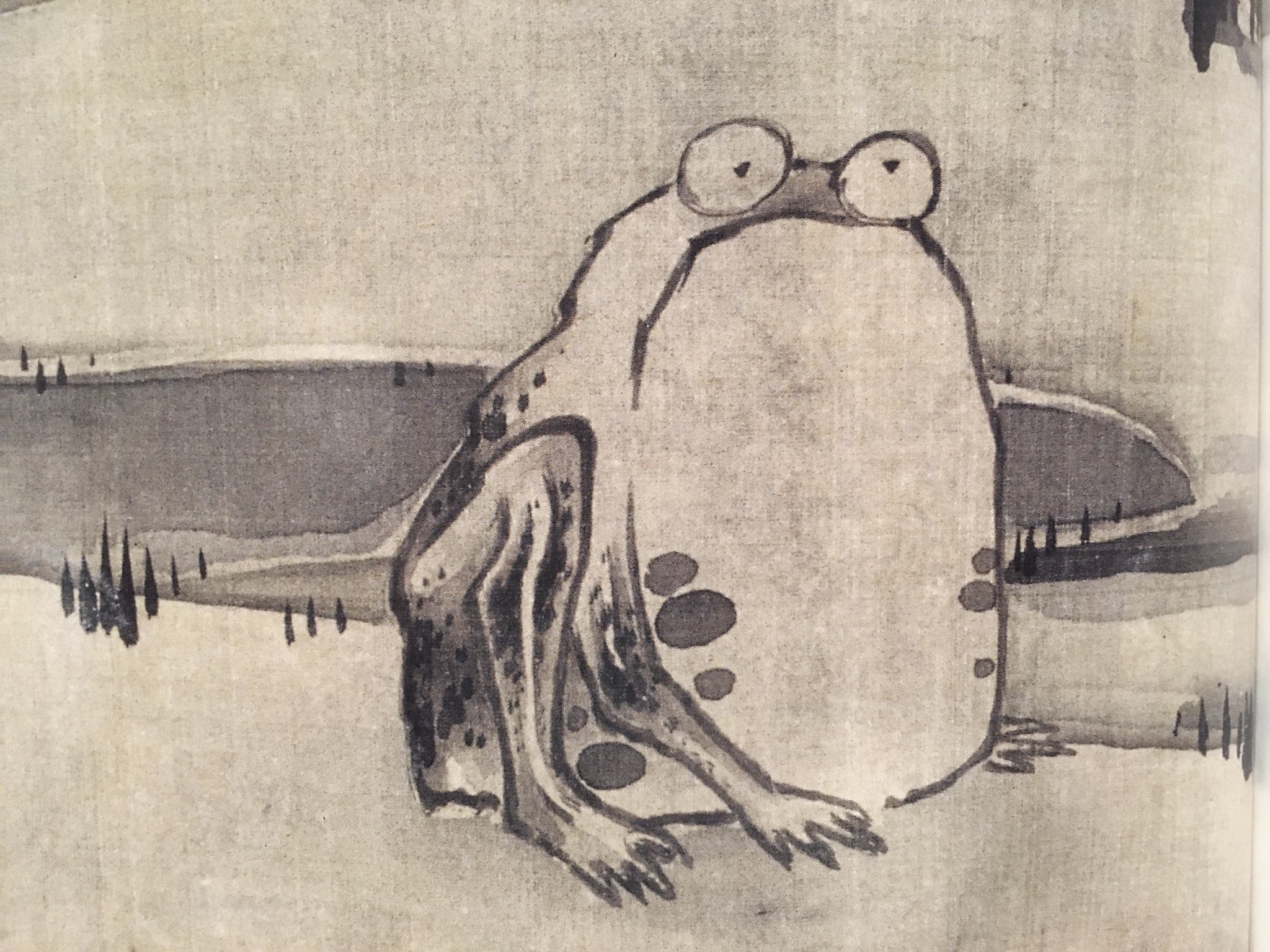

Daïchi Mori, Hikigaeru. Frog battle two, 2022

A characteristic aspect of your work involves the creation of long handscroll illustrations inspired by the tradition of emakimono. Why did you choose this format?

This format is “cinematographically speaking” very interesting for me, because I can write and draw the story in “one take”, since there are no pages: there is no frame, the viewer make their own framing as he is watching and going through the roll, they can expand or reduce the frame… They can just open the whole thing and look at the whole story at once, it’s very playful as a narrative storytelling technique and style.

In a way it’s a very avant-garde way to see a painting or a comic book, and paradoxically it is also a very ancient Asian technique.

Your work has been described as influenced by Itō Jakuchū, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Kazuo Umezu, and Suehiro Maruo*. This comparison spans two centuries and includes an eighteen-century Kyoto painter known for this depictions of animals (among them, some popular frogs), a great master of ukiyo-e, the father of terror manga, and one of the most known ero guro manga artists. Can you elaborate on the references to these artists?

As a contemporary artist I always believe I’m a “dwarf” compared to the ancient masters, so I like to jump on top of their shoulders to try to look beyond, never forgetting the ancient when I’m drawing. But at the same time, I’m also surrounded by so many contemporary things and styles… In a way, this is my little revolution: going back and forth through the ages, styles, cultures, in order to digest something new.

I’m also very sensitive to the “dark humor:” artists have always lived surrounded by chaotic periods (wars, catastrophes, pandemics…). This is not something “new,” like most people believe, the artist has to try to pull the funny part out of all that, try to make some poetry out of this chaos. I don’t like artists who are too dark, depressive, nor the “feel good” artists who ignore the bad part of the human being. I try to find a way to cry and laugh about the world.

“I don’t like artists who are too dark, depressive, nor the «feel good» artists who ignore the bad part of the human being. I try to find a way to cry and laugh about the world”

Your animations are particularly elaborated and, while they are clearly influenced by traditional Japanese painting, they incorporate obvious references to anime and action films. How do you conceive these animations, and how do they relate to the illustrated handscrolls?

These animations are sort of a “spin off” using a particular character or detail pulled out from the bigger rolls, so I can develop that particular character in different nonsense situations, again trying to recompose the chaos into something fun and aesthetic. Always contrasting with some elements from the ancient world, reminding us that our story is just going in cycles, like an eternal return.

Daïchi Mori, Hikigaeru. Frog battle three, 2022

In Higikaeru, a giant toad and its minions play the role of the nemesis of the hero. Given that frogs usually represent good fortune and a safe return home, why did you choose to make them evil?

For me there is no evil or good, especially in the animal kingdom. Animals are just defending themselves or acting as a group to attack the weakest one; but at the same time they came as a group because each one of them are weak on their own. My story is just inspired by what I see, all the “social life” for example. I’ve always wanted to be alone, not belong to any group, but all of the people around are trying to grab you into one particular group, “like a group of frogs trying to tear out your face” that’s the symbolic idea behind these recurrent animations. Emiko (the human kid) and Higikaeru (the frog) could be seen as good or bad, according to each episode, but again this is just a humanistic consideration.

Daïchi Mori, Hikigaeru. Frog battle three, 2022

The main character, Emiko, has his face ripped off, the skin dangling on the side. This turns him into a mysterious hero, who looks as if he’s wearing a mask. What inspired you to create this character?

It’s a personal way of seeing myself as an “unexisting” artist. I don’t want to be seen, nobody has seen a photo of me, I just want my art to be known, this is why the hero has no face, which makes him someone totally versatile, unrecognizable, he doesn’t need to wear a mask to survive in society, he exists just for what he represents and not for what he is.

In your exhibitions, your work usually takes the form of an installation, with a rather theatrical setup, dominated by light and darkness. What do you find interesting about this type of presentation?

This part comes more from the artist Nieto. He is a sort of video artist, and “stage director” of Opera. He really liked my work, and wanted to expose it, so he created this kind of theatrical installation inspired by my work.

Working with Nieto seems to have had a crucial impact in your career. Can you describe this collaboration?

At the beginning I didn’t want to exhibit my work, I thought my art was just for me, something intimate that nobody has to see (as with my face), but he insisted so much that finally my grandmother convinced me to do it. He also made a short animation movie, using my rolls, it’s not bad, it’s called “Swallow the Universe.”

Nieto created a documentary about your life and work that presents you as a hikikomori and almost as a fictional character. What do you think of this characterization?

It is very funny. I laughed when I saw it because it’s just a collage using images from the internet, but telling my own story. We Japanese are very open minded to this kind of auto-ironic style, so I really loved it because he managed to represent me in a very satiric way.

“What I love in general about this idea of metaverse and NFTs is that there is nothing physical there. I just want to work, isolated in my room, no need to go to a snobbish opening show”

You recently launched a sale of artworks as NFTs in the marketplace Objkt.com. Why did you choose the Tezos blockchain to sell your artworks? How has been your experience in the NFT space so far, both in terms of selling your work and participating in a community?

I actually first did a NFT release in ETH last year. After that I decided to try Tezos because the community seemed more prone in welcoming new artists, also the artworks are easier to collect there, the “gas fees” (transfer you pay to collect an artwork) are much lower and there and many experimental artists in the scene who don’t need to focus on the money but can focus also on expressing themselves.

What I love in general about this idea of metaverse and NFTs is that there is nothing physical there. That is exactly what I wanted. I just want to work, to be enclosed, isolated into my room with myself, no need to go to a snobbish opening show or meet people IRL. Also I like the idea of something international, “universal”, without stupid laws telling what I should or should not do.

* Notes: a bit of history of Japanese manga

Manga is the Japanese term for comics and cartoons, developed since the late 19th century but with deep roots in earlier artistic forms such as emakimono, painted narrative handscrolls depicting scenes from daily life that date back to the 8th century, as well as sketches and isolated “whimsical” drawings by ukiyo-e artists such as the celebrated Hokusai (1760 – 1849).

The artists mentioned in this interview, whose work has been compared to that of Daïchi Mori, draw an interesting genealogy within the evolution of Manga.

Itō Jakuchū (1716-1800) was known for his paintings of animals, particularly roosters and other birds, and his restrained and professional attitude, as well as his strong connection to Zen buddhism. His humorous sketches of animals with human-like personalities have been re-discovered in recent years to great acclaim. One of his drawings from 1790, a sketch of a frog, has been particularly popular.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798 – 1861) was a great master of ukiyo-e who worked in a wide range of genres, including scenes with legendary samurais, landscapes, portraits of kabuki actors and beautiful women. He is also widely known for his satirical drawings, in which he depicts cats with human traits, and woodblock prints populated by otherworldly creatures.

Kazuo Umezu (1936), manga artist, musician, and actor, is considered the godfather of horror manga, a genre he helped develop since the 1960s. Inspired by ghost tales and local legends his father told him when he was a child, his work combines supernatural horror with the goofy comedy of characters such as Makoto-Chan. His stories frequently include young boys and girls being attacked by skinless monsters and creatures with physical deformities.

Suehiro Maruo (1956) is a manga artist with an international cult following. His work contains graphic sex and violence, also frequently depicting body deformities, in what is known as ero-guro, or “erotic grotesque.” Mutilation, blood, gore, and explicit sex are commonly present in his unsettling illustrations, which are nevertheless executed with a masterful attention to detail and composition.