Pau Waelder

This interview is part of a series dedicated to the artists whose works have been selected at the SMTH + Niio Open Call for Art Students. The jury members Valentina Peri, curator, Wolf Lieser, founder of DAM Projects/ DAM Museum, and Solimán López, new media artist, chose 5 artworks that are being displayed on more than 60 screens in public spaces, courtesy of Led&Go.

Katsuki Nogami is a Japanese artist who studied at Olafur Eliasson’s Institut für Raumexperimente in Berlin and graduated from the Department of Imaging Arts and Science Musashino Art University in Japan. He has also studied at the Interface Cultures program at University of Art and Design in Linz (Austria) and is currently a residency artist at Cite des Arts in Paris. This extended international experience, alongside his public art works permanently installed in several cities in Japan, has given him a particular angle about identity and belonging. Exposed to discrimination in this studies abroad, he has decided to focus his work on how our facial features determine our identity in relation to those around us, and how technology mediates our interactions with each other.

Katsuki Nogami, Image Cemetery, 2023

You state that your work stems from the experience of feeling discriminated against during your time studying abroad. While the Internet and globalization promised a more closely connected and shared world, it seems that xenophobia and discrimination against those perceived as “others” has only increased. Would you say that social media and digital technologies have contributed to this situation?

I think the internet also enhanced localisation like a small community at first. Then it also made a closed environment and separated world, too. Actually I liked it. On the other hand, Twitter (X) is really boring currently because of its openness nowadays. Their openness only led to contentless eye-catching stuff because of Elon’s monetization. Because of this tendency to reward eye-catching content, streamers can end up performing seriously racist or controversial actions, like the person who said “I would do Hiroshima again,” or the model who has been accused of blackfishing to get brand endorsements.

I feel that the freedom and the inspiring movement of the early internet are gone. And it’s just a business society now. So my answer is that digital technologies helped us to communicate well, but social media is linked to xenophobia and discrimination.

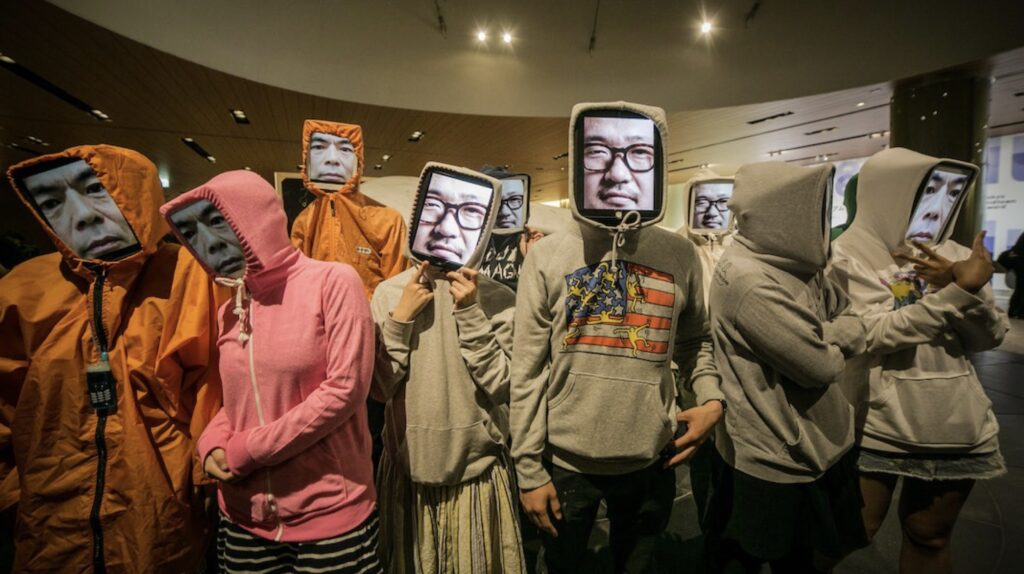

In the Yamada Taro project (2014-2021), you carried out an interesting experiment in establishing a dialogue with passersby and questioning identity as it is mediated by digital technologies. Can you tell me a bit more about this experience?

On the internet, there is no responsibility since you can be anyone. I think this leads to a loss of identity. So I wanted to express this tendency to anonymity without responsibility. At first, the reaction was just like drawing a card. Then I felt it was weird because I wanted to troll. Unlike the internet, you need to talk to people to get a face picture in person. After it, I tried to steal faces without talking and took faces from the Facebook event page of the opening. It was also when politicians acquired the right to use their accounts on Twitter in Japan. Some people imitated it before and had a bunch of followers, sometimes fake accounts are much more famous than real accounts. Now I also hide myself inside the hoodie for the performance, not as an artist. I wanted to be hidden from society since that was my initial intention.

“On the internet, there is no responsibility since you can be anyone”

In Heartfelt Spam and Monologues, you address the dark aspects of our online communications, somewhat playfully, but drawing attention to serious issues that affect people’s wellbeing and can have fatal consequences. It is telling that you create situations which invite viewers to participate and communicate as they wish. What has been their reaction? From this experience, do you think that we are aware of how technology is affecting our way to communicate with each other?

Both artworks deal with artificial conversations. Sometimes I don’t know if this person who chatted with me exists or not. There are 8 fake accounts of me on Twitter. I feel that social media has deeply changed our way of communicating with each other. The messages we post are intended for a large group of anonymous people, not for just one person, as in a conversation. This should be clear and understandable to everyone. Social communication tends to be public, so you shouldn’t open a dialogue with a specific person, because it leads to a closed community. I feel that this is the main transition of the internet: at first it was closed localisation but now it’s globalization which has lost its identity. Talking directly to one another, or expressing yourself in a unique way is no longer expected, you should be addressing a wide audience in a language that is closer to a marketing pitch or a press release than to your individual voice. Even when this communication takes place visually, as it happens on Instagram or Tiktok, all posts look similar, don’t you think?

Rekion Voice (with Taiki Watai) is a particularly critical take on technology, showing also a dark side of machines, that reminds of Jean Tinguely’s kinetic installations and Norman White’s robots. How would you contextualize this installation and performance in relation to your other artworks about human communication and identity?

It’s part of the Japanese dark side, I think. In Japan, they try to make robots cute, like your pet. In nursing facilities or elderly homes, there are some people who use friend robots or nurse robots. Normally robots imitate animals to be used as pets. Jean Tinguely’s kinetic installations and Norman White’s robots are helpless machines, just a mechanism. In Japan, there is Animism, which is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. However, if robots are pets, they ought to be treated as slaves: they are there to serve us. That was my inspiration in this installation, showing machines as servants but also as menacing creatures. And this is the difference between my work and Tinguely’s or White’s approach to machines. At the same time, I consider that robots become a mirror of ourselves. Watching a robot is like looking at oneself, and at the same time feeling that the robot is in itself a being with its own identity, that is returning our gaze.

“Watching a robot is like looking at oneself, and at the same time feeling that the robot is in itself a being with its own identity, that is returning our gaze.”

As a student in the University of Linz and Paris 8, you have had the opportunity to discover the many aspects of digital art at the Ars Electronica festival and other events happening in Linz and Paris. What has the education in these universities brought to your artistic practice? How would you compare your experience in Linz and Paris, also in terms of the feelings of discrimination you have expressed when studying abroad?

I attended the Ars Electronica festival in 2014 for the first time. Then I got a prize in the Sound Art category in 2017. I participated in the Ars Electronica festival many times, so I felt the transition from the event being a host to individual artistic projects like the ones I exhibited, to focusing on larger trends in society. I also feel that the whole digital art community is moving closer to the structures of the contemporary art world and its attention to production studios and market trends.

The most notorious thing I have noticed in the education system is the fact that in the EU, the atmosphere is very different and less competitive than in Japan. In most European universities, you don’t need to pay directly to get into the university. The art school in the university where I studied in Japan costs 10,000 € per year, plus an entrance fee of 10,000 €. Also, in Japan we don’t have a gap year and entering a company is only for new graduates. So students in Japan are really competitive and eager. Between Linz and Paris, the finance difference was notable for me, since Media Art needs a lot of equipment… Paris 8 lent me 3 PCs at the same time for daily creation. Of course strong discrimination is everywhere. But I feel invisible or micro aggression against Asians is more familiar and I’m struggling from it. When you are part of a minority, you always need to plan and think well. Young people learned they shouldn’t offend others because of their race. So then, they stopped interacting with people from minorities to avoid dealing with their racism and discrimination. This is what I feel when people ignore me.

You have taken your work to dialogue with people on the street and outside of art exhibitions and institutional spaces. What do you think of the opportunity to display it now in 30+ screens on shopping malls in the context of the SMTH + Niio open call?

I like public art because it can be freely approached by a wide audience. Museums are closed spaces. When I mention the internet, everyone knows that context for now, but it doesn’t have a constraint like the theater. It’s the conflict but we just need an interesting topic. When I got a prize to show my video in similar conditions in China, I was denied the opportunity to display it in public, even though I was selected. So I’m relieved that I can show my video at this opportunity.

“I like public art because it can be freely approached by a wide audience. Museums are closed spaces.”

Image Cemetery, your winning artwork, is an intervention in the public space in which you integrate your image on rocks and stones, something that evokes primitive cultures and ancient rituals rather than digital technologies. What is different about this project from previous works in terms of exploring the notion of identity?

It started when I did my residency program in Kyoto during COVID-19. I was sick of the internet interactions with other people via zoom. When the internet became so convenient, everyone tried to escape from it. Zoom was like a jail to keep us in front of the desk. So I tried to go outside and find nature. I printed my face almost everyday. It’s because I wanted to see my differences and check that my body is growing. Stone is representative of this world in Buddhism. Kyoto is a very ancient city which connects to the after world everywhere. It reminded me of artworks after my death as evidence of living. Now everyone is a photographer with a smartphone, but they don’t print it. It’s difficult to throw away your grandparent’s heavy album. I thought this is a kind of art with an aura. So I wanted to create this. Image is very high resolution to show raw faces in public since it’s normal to put filters to get rid of stains or acne from the skin.

Actually, it was a very good change since I could find my possibility to create real material. It’s not a new technique, but I felt artists can invent when they learn. NFT is kind of a big representative of the internet in COVID-19. After that, that trend is gone. And many artists have also focused on natural materials.

Viewers thought it was weird, and they also felt it was alive, somehow. So I feel that my objective was achieved. But I was a bit sad when the river washed away my stones. And someone stole some of them, too. Also, a person from Iraq told me stones are tools of warfare. It was inspiring because nature is different based on each person’s beliefs.