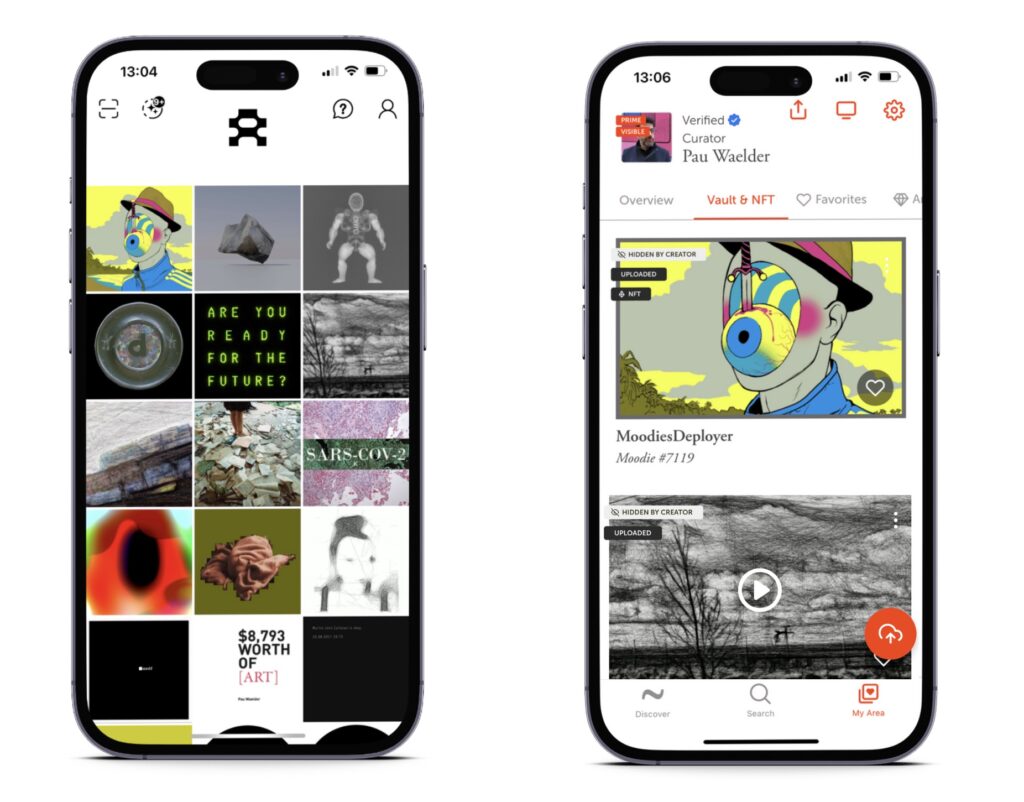

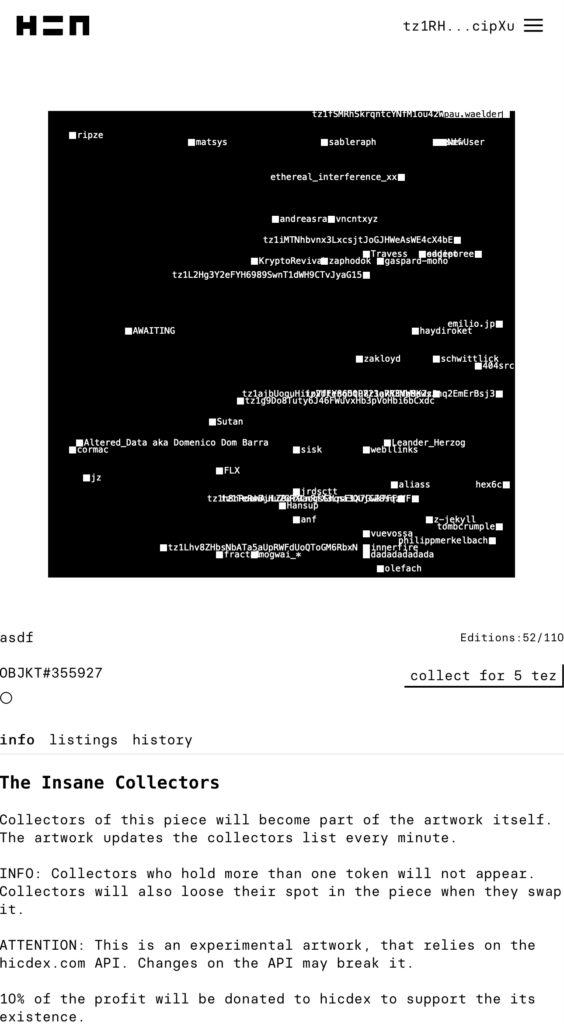

Pau Waelder

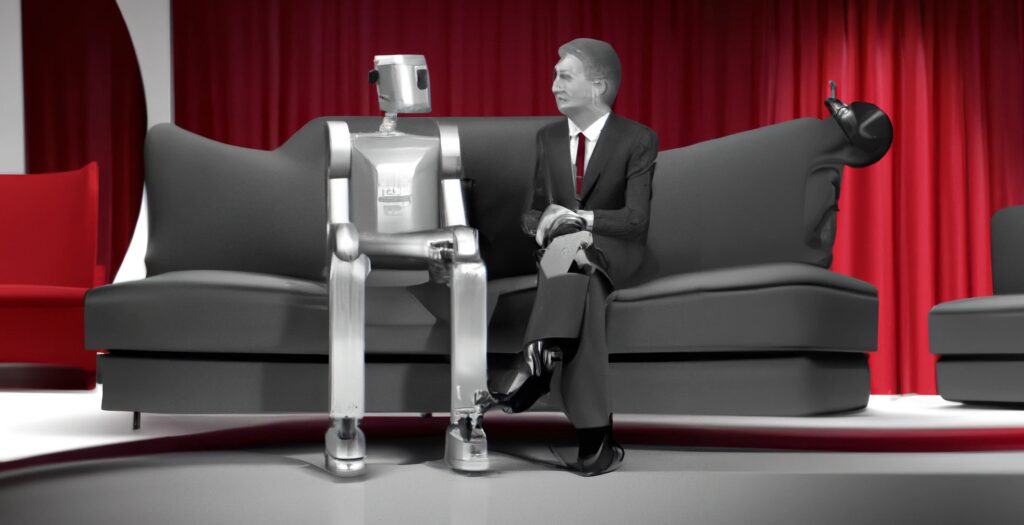

ChatGPT is a machine learning model developed by OpenAI which was recently opened to the public as a research preview, allowing users to test it freely. Similarly to how DALL-E 2 draw widespread attention for its ability to create impressively realistic or stylized images based on text prompts, ChatGPT is now receiving similar responses, since it is capable of producing reasoned explanations and provide answers to follow-up questions, apparently grasping the context of what is being asked. As explained by OpenAI, the model was trained using supervised learning, based on conversations written by humans, in which a question and an answer were provided. Then a reward model was trained using several answers to the same question and having a human labeler rank them from best to worst. A reinforcement learning algorithm was used to optimize the model.

ChatGPT is able to explain concepts and provide answers considering different aspects of an issue, often maintaining a neutral attitude that seeks to balance out opposing points of view. It usually concludes with a short paragraph that summarizes its previous statements. Seeking to test it, I asked a series of questions regarding art created with Artificial Intelligence programs. It seemed fitting to have an AI system explain AI art to humans. The result is the interview below.

Please note: ChatGPT provides long answers, sometimes using repetitive formulas. I have decided not to make any edits to the text in order to remain true to its outputs, and so to avoid forcing readers to scroll through a very long article I’ve included an index below. Feel free to click on the questions you find most interesting. They are grouped into themes to make browsing easier.

Definitions and history

- What is AI Art?

- Is AI Art a subset of algorithmic art?

- What role does AI art play in the history of contemporary art?

- How did AI art come about?

- Which was the first AI artwork ever created?

- Can you name the main AI artists?

Creativity

- Who creates the art, the artist or the machine?

- How can an algorithm be an artist? Isn’t creativity exclusively human?

- Why would an AI program create art for humans? Wouldn’t it be more interesting to create art that only another AI can understand?

- Who should sign an artwork created with AI?

- If AI programs are written by humans, isn’t AI art entirely created by humans, in the end?

Production

- Which tools are there to create AI art?

- Which are the most commonly used AI programs?

- Which programming languages are used to create AI art?

- Does an artist need to code to create this type of art?

- Do you need a very powerful computer?

- Does this mean, then, that only a handful of artists can create AI art?

- Will AI make artists lazy?

- Can it lead to an overproduction of art?

Environmental impact

- What is the environmental impact of all of this?

- And if in the future many more artists can use AI programs and these are resource-intensive, does this mean that AI art can be bad for the planet?

Aesthetics

- Do people really like AI art, or are they in it just for the novelty?

- Why do most AI generated artworks produce nightmarish images?

- Why does GAN generated art look like bad painting?

- Should we reconsider our notions of art when exploring art made with AI?

Market

- Is AI art a good investment?

- When selling art created with AI, should the artist split their benefits with the AI program?

Longevity

- Will AI-generated art be preserved in the same way as paintings and sculptures? Will it last for centuries?

- Will it replace other forms of art making?

- Do you think that AI art will get better with time?

- Over its history, AI technology has frequently promised more than it could deliver. Is this the case with AI art right now?

What is AI art?

AI art is artwork created by artificial intelligence. This can take a variety of forms, but typically involves using algorithms and machine learning techniques to generate visual artwork, music, or other forms of creative expression. AI art often explores the intersection of art and technology, and can involve the use of neural networks and other forms of AI to create unique and unpredictable artistic experiences. Some AI art is created with the goal of imitating human creativity, while other AI art is intended to push the boundaries of what is possible with technology and create entirely new forms of art.

AI art is a type of art that is created using artificial intelligence algorithms and technology. AI art can take many forms, including digital art, paintings, sculptures, and other types of visual art. The algorithms and technology used in AI art can be trained to create original works of art or can be used to enhance or manipulate existing artwork. AI art can be created by both human artists and AI algorithms working together, or it can be created entirely by AI.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Is AI art a subset of algorithmic art?

AI art can be considered a subset of algorithmic art. Algorithmic art is a term that refers to art that is created using algorithms and other computational processes. AI art is a specific type of algorithmic art that is created using AI technology and algorithms.

In this sense, AI art can be considered a subset of algorithmic art, because it is a specific type of art that is created using algorithms and computational processes. However, it is worth noting that not all algorithmic art is AI art, and there are many other types of algorithmic art that do not use AI technology.

Overall, while AI art is a type of algorithmic art, it is not the only type of algorithmic art, and there are many other types of algorithmic art that do not use AI technology.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Not all algorithmic art is AI art, and there are many other types of algorithmic art that do not use AI technology.

What role does AI art play in the history of contemporary art?

AI art is a relatively new development in the history of modern and contemporary art, and its role is still evolving. However, AI art has already had a significant impact on the art world, and it has introduced new ideas and possibilities for artists and art enthusiasts.

One of the key ways in which AI art has impacted the art world is by challenging traditional notions of what constitutes art and who can create it. Because AI algorithms and technology can be used to create art without the need for human intervention, AI art has called into question the idea that art must be created by human artists in order to be considered “real” art.

Additionally, AI art has also introduced new possibilities for collaboration between human artists and AI technology. Many artists are now experimenting with using AI algorithms and technology as part of their creative process, and this has led to the emergence of new styles and genres of art that are not possible without the use of AI technology.

Overall, while AI art is a relatively new development in the history of modern and contemporary art, it has already had a significant impact on the art world, and it is likely to continue to play an important role in the future.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

How did AI art come about?

AI art has its roots in the field of artificial intelligence (AI), which is the study of how to create computer systems that can simulate human intelligence. The development of AI technology has been ongoing for several decades, and it has led to the creation of many different AI algorithms and technologies that can be used to solve complex problems and to automate various tasks.

One of the areas in which AI technology has been applied is in the creation of art. By training AI algorithms on large datasets of artwork, it is possible to create AI programs that can generate novel and original artworks based on the information they have learned.

The first known examples of AI art date back to the 1960s, when researchers began to experiment with using AI algorithms to create visual art. Since then, the field of AI art has continued to evolve and grow, and there are now many different AI algorithms and technologies that can be used to create a wide range of different types of art.

Overall, AI art has come about as a result of the development of AI technology and algorithms, and the application of these technologies to the field of art.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Which was the first AI artwork ever created?

The first known examples of AI art date back to the 1960s, when researchers began to experiment with using AI algorithms to create visual art. One of the first known AI artworks was created by the computer scientist Harold Cohen in the early 1960s. Cohen developed a program called AARON, which was able to create abstract drawings based on a set of rules and instructions that Cohen provided.

Another early example of AI art was created by the artist Harold Cohen in the early 1970s. Cohen developed a program called AARON, which was able to create abstract drawings based on a set of rules and instructions that Cohen provided.

Overall, while the exact details of the first AI artwork are not well-documented, it is likely that one of the first AI artworks was created by Harold Cohen in the early 1960s.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Can you name the main artists who have created art with AI?

There are many artists who have created art using AI technology and algorithms. Some of the most notable and well-known artists who have created AI art include:

- Mario Klingemann: Klingemann is a German artist who creates AI art using a variety of different algorithms and technologies. His work often explores the intersection of art and technology, and he has exhibited his AI art in galleries and museums around the world.

- Trevor Paglen: Paglen is an American artist who creates AI art that explores the relationship between technology, surveillance, and power. His AI artworks often take the form of large-scale installations and projections, and he has exhibited his work in galleries and museums around the world.

- Anna Ridler: Ridler is a British artist who creates AI art using deep learning algorithms and machine learning techniques. Her AI art often explores themes of identity and the human condition, and she has exhibited her work in galleries and museums around the world.

- Sougwen Chung: Chung is a Canadian artist who creates AI art that explores the relationship between humans and machines. Her work often involves collaborative projects between human artists and AI algorithms, and she has exhibited her AI art in galleries and museums around the world.

Overall, there are many artists who have created AI art, and their work covers a wide range of styles, techniques, and themes. These artists are at the forefront of exploring the potential of AI technology and algorithms to create art, and their work has been exhibited and recognized in galleries and museums around the world.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Who creates the art, the artist or the machine?

Both the artist and the machine can create AI art. Some AI art is created entirely by AI algorithms, without any human input. In these cases, the algorithms themselves are the “artists” creating the artwork. Other AI art is created by human artists using AI technology and algorithms to assist them in the creative process. In these cases, the human artist is the creator of the artwork, but the AI technology and algorithms are an important part of the creative process. In some cases, AI art may be created by a collaboration between a human artist and AI algorithms, with both contributing to the final artwork.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

How can an algorithm be an artist? Isn’t creativity exclusively human?

The question of whether creativity is exclusively human is a complex one, and there is no definitive answer. Some people believe that creativity is a uniquely human trait, while others believe that it is possible for machines and algorithms to be creative.

One way to approach this question is to consider what we mean by creativity. Creativity can be defined as the ability to produce something new and original. While this definition may seem to exclude machines and algorithms, it is important to remember that these tools can be used in ways that were not possible before, and that they can help us to explore new ideas and create new and original works of art.

The algorithms themselves can be seen as creative agents, capable of producing new and original works of art.

In the case of AI art, the algorithms and technology used can be trained on vast amounts of data and can be designed to explore a wide range of possibilities. This can allow the algorithms to generate artwork that is novel and original, even if it is created entirely by a machine. In this sense, the algorithms themselves can be seen as creative agents, capable of producing new and original works of art.

Ultimately, whether we consider AI art to be the work of a human artist, the machine, or a collaboration between the two, will depend on our individual perspectives and values. What is important is that AI art allows us to explore new possibilities and to create art in ways that were not previously possible.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Why would an AI program create art for humans? Wouldn’t it be more interesting to create art that only another AI can understand?

AI programs can create art for humans or for other AI programs, depending on the specific goals and objectives of the program and the designers who created it. In some cases, an AI program may be designed to create art that only another AI program can understand, for example, as part of a research project or to explore the capabilities of AI algorithms.

However, in many cases, AI programs are designed to create art that can be understood and appreciated by humans. This is because art is often a way for people to express themselves and to communicate with others, and creating art that can be understood and appreciated by humans is an important part of this process.

Additionally, creating art that can be understood and appreciated by humans can also help to demonstrate the capabilities of AI technology and algorithms. By creating art that people can understand and appreciate, AI programs can show the potential of AI technology to generate novel and interesting ideas, and to explore new creative possibilities.

Overall, whether an AI program creates art for humans or for other AI programs will depend on the specific goals and objectives of the program and the designers who created it.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Who should sign an artwork created with AI?

The question of who should sign an artwork created with AI is a complex one, and there is no definitive answer. The specific approach that an artist takes when signing AI-generated art will depend on the individual artist and their goals and values.

In some cases, an artist may choose to sign an artwork created with AI themselves, as the primary creator of the artwork. This could be because the artist believes that they were the primary driving force behind the creation of the artwork, and that the AI program was only a tool that was used to assist in the creative process.

On the other hand, some artists may choose to sign the artwork with the name of the AI program that was used to create the art. This could be seen as a way of recognizing the contributions of the AI program to the creation of the artwork, and it could be an interesting and unique way to explore the relationship between human artists and AI technology.

In some cases, an artist may choose to sign an artwork created with AI using both their own name and the name of the AI program. This could be seen as a way of recognizing the contributions of both the human artist and the AI program to the creation of the artwork.

Ultimately, the approach that an artist takes when signing AI-generated art will depend on their individual goals and values. Some artists may choose to sign the artwork themselves, while others may choose to sign it with the name of the AI program, and still others may choose a combination of both. What is important is that the artist is transparent about their approach and that they are fair and reasonable in their dealings with the AI program and any other parties involved.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

If AI programs are written by humans, isn’t AI art entirely created by humans, in the end?

It is true that AI programs are written by humans, and that the technology and algorithms used in AI art are created by humans. However, it is important to remember that AI programs are not just simple, pre-programmed tools that are used by human artists. Instead, AI programs are capable of learning from data and of making decisions and predictions based on that learning.

In the case of AI art, this means that the AI algorithms and technology are not just blindly executing instructions that have been written by humans. Instead, the AI algorithms are able to generate novel and original artwork based on the information they have learned from the training data.

This means that while AI art is not created entirely by humans, it is also not created entirely by AI algorithms. Instead, it is the result of a collaboration between human creators and AI technology, with both playing important roles in the creation of the final artwork.

Overall, while AI art is not created entirely by humans, it is also not created entirely by AI algorithms. Instead, it is the result of a collaboration between human creators and AI technology.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Which tools are there to create AI art?

There are many different tools and technologies that can be used to create AI art. Some of the most commonly used tools and technologies for creating AI art include:

- Machine learning algorithms, such as neural networks, that can be trained on data to generate art

- Generative adversarial networks (GANs), which can be used to create realistic images and other types of art

- Deep learning algorithms, which can be used to create detailed and complex artworks

- Computer vision algorithms, which can be used to analyze and interpret visual information

- Natural language processing algorithms, which can be used to generate text-based art, such as poetry or fiction

These are just a few examples of the tools and technologies that can be used to create AI art, and there are many other options available. The specific tools and technologies used to create AI art will depend on the individual artist and their goals and objectives.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Which are the most commonly used AI programs?

There are many different AI programs and technologies that are commonly used for creating AI art. Some of the most commonly used AI programs include:

- GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks): GANs are a type of AI algorithm that is often used for creating AI art. GANs consist of two neural networks – a generator network and a discriminator network – that work together to generate novel and original artworks based on a dataset of existing artwork.

- Style transfer algorithms: Style transfer algorithms are a type of AI algorithm that is used to apply the style of one image to another image. This can be used to create AI art by applying the style of a famous painting or artist to a new image, creating a novel and original artwork that combines the style of the original with the content of the new image.

- Evolutionary algorithms: Evolutionary algorithms are a type of AI algorithm that is inspired by the principles of natural selection and evolution. These algorithms can be used to create AI art by starting with a population of random artworks, and then using a set of rules and criteria to select the “fittest” artworks from each generation, allowing the art to evolve over time.

- Deep learning algorithms: Deep learning algorithms are a type of AI algorithm that is based on the structure and function of the human brain. These algorithms can be used to create AI art by training the algorithm on a dataset of existing artworks, and then using the trained algorithm to generate novel and original art.

Overall, there are many different AI programs and technologies that are commonly used for creating AI art, and the specific program that is used will depend on the goals and objectives of the artist.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Which programming languages are used to create AI art?

There are many different programming languages that can be used to create AI art. Some of the most commonly used programming languages for creating AI art include:

- Python: Python is a popular and versatile programming language that is often used for AI and machine learning applications. It has a large and active community of developers and users, and it offers a wide range of libraries and tools for working with AI algorithms and technology.

- R: R is a programming language that is commonly used for statistical computing and data analysis. It has a strong focus on data visualization and is often used for creating AI art that involves the generation of complex images and other visual elements.

- JavaScript: JavaScript is a popular programming language that is often used for web development. It is a versatile language that can be used for a wide range of different AI and machine learning applications, including the creation of AI art.

- Java: Java is a popular and widely used programming language that is often used for developing large-scale, enterprise-level applications. It is a versatile language that can be used for creating AI art, and it has a large and active community of developers and users.

These are just a few examples of the programming languages that can be used to create AI art, and there are many other options available. The specific programming language that is used to create AI art will depend on the individual artist and their goals and objectives.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Does an artist need to code to create this type of art?

An artist does not necessarily need to know how to code in order to create AI art. While knowledge of coding can be helpful for creating AI art, it is not a requirement.

There are many different tools and technologies available that can be used to create AI art without needing to know how to code. For example, there are several user-friendly AI platforms and tools that can be used to create AI art without needing to know how to code. These tools often provide a simple, intuitive interface that allows users to create AI art by dragging and dropping different elements and using pre-defined algorithms and settings.

There are many artists who collaborate with coders and other technical experts to create AI art.

Additionally, there are many artists who collaborate with coders and other technical experts to create AI art. In these cases, the artist can focus on the creative aspects of the art, while the coders and technical experts handle the technical aspects of creating the AI art.

Overall, while knowledge of coding can be helpful for creating AI art, it is not a requirement, and there are many different tools and technologies available that can be used to create AI art without needing to know how to code.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Do you need a very powerful computer?

The specific hardware requirements for creating AI art will depend on the specific AI algorithms and technologies that are being used, as well as the complexity and scale of the artworks being created. In general, however, creating AI art often requires a significant amount of computing power, and it is not something that can be done on a standard desktop or laptop computer.

In many cases, creating AI art will require the use of a high-performance computer with a powerful processor and a large amount of RAM. This type of computer will be able to handle the complex computations and data processing that is required for creating AI art, and it will be able to generate high-quality artworks in a reasonable amount of time.

Additionally, some AI algorithms and technologies may require the use of specialized hardware, such as graphics processing units (GPUs), in order to run efficiently and to generate high-quality artworks. In these cases, a computer with one or more powerful GPUs will be required in order to create AI art.

Overall, while the specific hardware requirements for creating AI art will vary depending on the algorithms and technologies being used, it is generally a resource-intensive task that requires a powerful computer with a large amount of computing power.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Does this mean, then, that only a handful of artists can create AI art?

The ability to create AI art is not limited to a small group of artists. While creating AI art does require a certain level of technical expertise and access to the necessary tools and technologies, these are not necessarily difficult or expensive to obtain.

There are many different tools and technologies available that can be used to create AI art, and many of these are freely available or can be purchased at a low cost. Additionally, there are many online resources and tutorials that can help artists to learn the technical skills and knowledge that are needed to create AI art.

Anyone who is interested in creating AI art can learn the necessary skills and obtain the necessary tools and technologies

As a result, while creating AI art does require some technical expertise and access to the necessary tools and technologies, it is not something that is limited to a small group of artists. Anyone who is interested in creating AI art can learn the necessary skills and obtain the necessary tools and technologies, and there are many different resources available to help them do so.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Will AI make artists lazy?

The use of AI technology in the creation of art will not necessarily make artists lazy. In fact, AI technology can be a powerful tool that can assist artists in the creative process and help them to explore new ideas and possibilities.

However, it is important to remember that AI technology is just a tool, and it cannot replace the creativity and vision of human artists. While AI algorithms and technology can be used to generate suggestions or ideas for artwork, it is ultimately up to the human artist to decide which ideas to pursue and how to incorporate them into their work.

Additionally, the use of AI technology in the creation of art can also help to inspire and challenge artists to think in new ways and to push the boundaries of what is possible. In this way, the use of AI technology can actually encourage artists to be more creative and innovative, rather than making them lazy.

Overall, while the use of AI technology in the creation of art can be a powerful tool, it will not necessarily make artists lazy. Instead, it can assist artists in the creative process and help them to explore new ideas and possibilities.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Can it lead to an overproduction of art?

The use of AI programs in the creation of art could potentially lead to an overproduction of art. Because AI algorithms and technology can be used to generate art quickly and efficiently, it is possible that the use of AI could result in a large number of artworks being produced in a short period of time.

However, it is important to remember that the use of AI in the creation of art is not a new development, and it has been happening for several years. As a result, the art market has already had time to adjust to the use of AI technology, and the potential for overproduction of art is not as great as it may seem.

Additionally, it is worth considering that the quality and value of AI-generated art will vary, and not all AI-generated art will be of equal quality or worth. This means that while there may be a large number of AI-generated artworks produced, not all of them will be considered valuable or worth collecting.

Overall, while the use of AI programs in the creation of art could potentially lead to an overproduction of art, the potential for overproduction is not as great as it may seem, and the quality and value of AI-generated art will vary.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

What is the environmental impact of all of this?

The environmental impact of creating AI art will depend on a variety of factors, including the specific tools and technologies that are being used, the amount of computing power that is required, and the conditions under which the art is created.

In general, however, creating AI art can be a resource-intensive process that requires a significant amount of computing power. This can have an impact on the environment, both in terms of the energy that is consumed and the potential for electronic waste.

Additionally, some AI algorithms and technologies may require the use of specialized hardware, such as graphics processing units (GPUs), which can be expensive to purchase and difficult to dispose of in an environmentally-friendly manner.

Overall, the environmental impact of creating AI art will depend on the specific tools and technologies that are being used, and it is important for artists to consider this impact when creating AI art. There are many different ways to reduce the environmental impact of creating AI art, such as using energy-efficient hardware and recycling or repurposing old or obsolete technology.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

And if in the future many more artists can use AI programs and these are resource-intensive, does this mean that AI art can be bad for the planet?

If the use of AI programs for creating art becomes more widespread in the future, it is possible that it could have a negative impact on the environment. As more and more artists use AI algorithms and technology to create art, the demand for computing power and specialized hardware will increase, and this could lead to an increase in energy consumption and electronic waste.

However, it is important to note that the potential negative impact of creating AI art on the environment is not unique to AI art, and it is something that is also a concern for other forms of art making that are resource-intensive. Additionally, it is also possible that advancements in AI technology and algorithms could lead to more efficient and environmentally-friendly ways of creating AI art, which could help to mitigate the potential negative impact on the environment.

Overall, while the use of AI programs for creating art could potentially have a negative impact on the environment, this is not unique to AI art, and it is something that can be addressed through the use of efficient and environmentally-friendly technology and practices.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Do people really like AI art, or are they in it just for the novelty?

It is difficult to say whether people truly like AI art, or if they are simply interested in its novelty. There are certainly many people who are intrigued by the idea of AI art, and they may be drawn to these artworks because they are something new and different.

However, there are also many people who genuinely appreciate the aesthetic qualities of AI art, and who enjoy the unique perspective and ideas that these artworks can offer. Some people may find AI art to be thought-provoking and engaging, and they may enjoy the challenge of trying to understand and interpret these artworks.

Overall, it is likely that people’s reactions to AI art will vary, and there will be some people who are interested in it simply because it is novel, while others will genuinely appreciate and enjoy the art itself.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

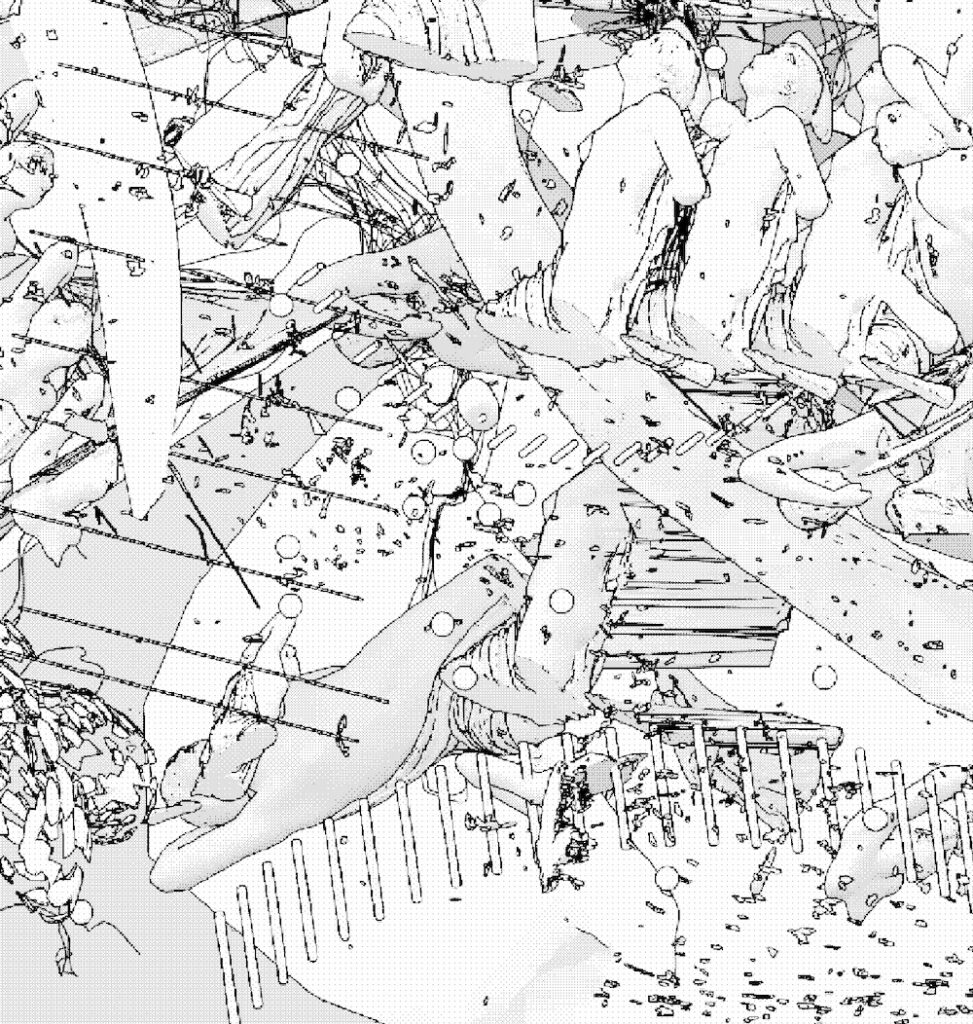

Why do most AI generated artworks produce nightmarish images?

Most AI-generated artworks do not produce nightmarish images. In fact, many AI-generated artworks are quite beautiful and interesting. However, it is true that some AI-generated artworks can produce images that some people might find disturbing or unsettling.

There are a few reasons why this may be the case. One reason is that AI algorithms are designed to explore a wide range of possibilities, and this can sometimes result in the generation of images that are unusual or unexpected. Another reason is that the training data used to teach the AI algorithm may contain images that some people find disturbing, and this can influence the types of images the algorithm generates.

It is also worth noting that what one person finds disturbing or nightmarish may not be the same for another person. What is considered “nightmarish” is a matter of personal opinion, and different people may have different reactions to the same image.

Overall, while some AI-generated artworks may produce images that some people find disturbing, this is not the case for all AI-generated art, and many AI-generated artworks are beautiful and interesting.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Why does GAN generated art look like bad painting?

Not all GAN-generated art looks like bad painting. GANs, or Generative Adversarial Networks, are a type of AI algorithm that can be used to generate art, and the specific appearance of the art generated by a GAN will depend on the training data and other factors.

It is true that some GAN-generated art may appear to be low-quality or “bad” painting. This can happen for a few reasons. One reason is that the training data used to teach the GAN may not be of high quality, which can result in the GAN generating art that is less detailed or less realistic than it could be. Another reason is that the GAN may not be trained for a long enough time, or it may not be trained on a large enough dataset, which can also result in lower-quality art.

It is also worth noting that what one person considers to be “bad” painting may not be the same for another person. Beauty and quality are subjective, and different people may have different opinions about the same artwork.

Overall, while some GAN-generated art may appear to be low-quality or “bad” painting, this is not the case for all GAN-generated art, and the specific appearance of GAN-generated art will depend on a variety of factors.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Should we reconsider our notions of art when exploring art made with AI?

The use of AI technology and algorithms to create art can certainly challenge our traditional notions of art and the creative process. Because AI algorithms and technology can be used to create art without the need for human intervention, AI art calls into question the idea that art must be created by human artists in order to be considered “real” art.

Additionally, AI art can also challenge our ideas about what makes art valuable and interesting. Because AI algorithms are able to generate artworks that are highly detailed and complex, they can create art that is aesthetically pleasing and engaging. This can challenge the idea that art must be created by human artists in order to have value or meaning.

Overall, exploring AI art can certainly lead us to reconsider our notions of art and the creative process. By challenging our traditional ideas about what constitutes art and what makes art valuable, AI art can help us to see art in new and interesting ways.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Is AI art a good investment?

The potential for AI art to be a good investment will depend on a variety of factors, including the specific artworks being considered, the reputation and track record of the artist, and the overall state of the art market.

In general, however, AI art is still a relatively new and untested area of the art market, and there is a lot of uncertainty around the value and potential appreciation of AI artworks. Many buyers and collectors may be hesitant to invest in AI art due to its novelty and the lack of a track record for these types of artworks.

Additionally, the market for AI art is still relatively small, and there may not be a large number of buyers and collectors who are interested in these artworks. This could limit the potential for AI art to appreciate in value over time, and it could make it difficult for investors to find buyers for their AI artworks.

Overall, while there may be some potential for AI art to be a good investment, there are also many factors that could limit its value and potential appreciation. It is important for investors to carefully consider these factors before deciding to invest in AI art.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

When selling art created with AI, should the artist split their benefits with the AI program?

Whether or not an artist should split their benefits with an AI program when selling art created with AI will depend on the specific circumstances and the agreement between the artist and the AI program. In some cases, the artist and the AI program may have agreed to share the benefits from the sale of the art, in which case the artist would need to split their benefits with the AI program.

However, in other cases, the artist and the AI program may not have agreed to share the benefits from the sale of the art. In these cases, the artist would not be obligated to split their benefits with the AI program, and they would be entitled to keep all of the proceeds from the sale of the art.

Ultimately, whether or not an artist should split their benefits with an AI program when selling art created with AI will depend on the specific circumstances and the agreement between the artist and the AI program. It is always a good idea for the artist and the AI program to carefully consider and agree on these issues before starting to create art together.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Will AI-generated art be preserved in the same way as paintings and sculptures? Will it last for centuries?

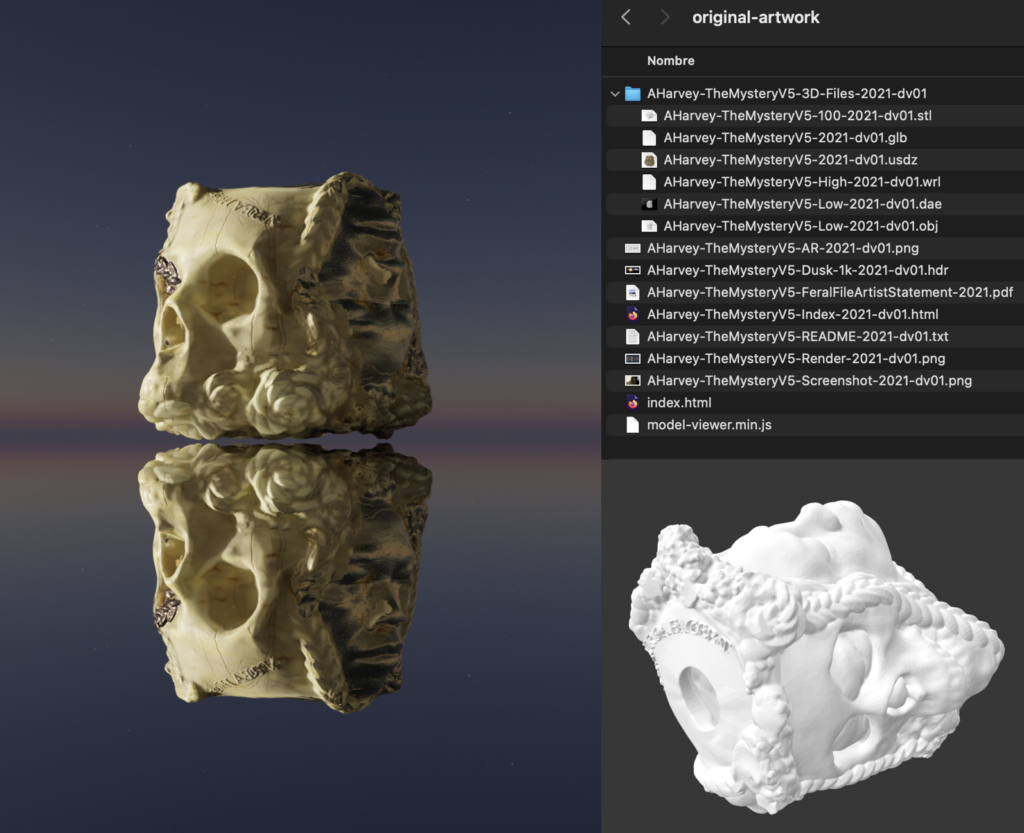

It is not clear whether AI-generated art will be preserved in the same way as paintings and sculptures. The preservation of art is a complex process that involves a variety of factors, including the materials used to create the art, the conditions in which the art is stored, and the care and attention given to the art over time.

In the case of AI-generated art, the specific approach to preservation will depend on the materials and technology used to create the art. For example, some AI-generated art may be created using digital media, such as video or audio, which may be more susceptible to degradation or loss over time. In these cases, the art may require special preservation techniques in order to ensure that it is preserved for future generations.

On the other hand, some AI-generated art may be created using physical materials, such as paint or clay, which may be more durable and easier to preserve over time. In these cases, the art may be more likely to last for centuries, just like traditional paintings and sculptures.

Overall, the preservation of AI-generated art will depend on the materials and technology used to create the art, as well as the care and attention given to the art over time. It is not clear whether AI-generated art will be preserved in the same way as traditional paintings and sculptures, and it will ultimately depend on the specific artworks and the circumstances in which they are created.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Will it replace other forms of art making?

It is unlikely that AI-generated art will replace other forms of art making. While AI technology and algorithms can be used to create interesting and novel artworks, they are not a replacement for the creativity and vision of human artists.

Additionally, there are many different forms of art making, and the use of AI technology and algorithms is just one of many different approaches that artists can take. As a result, it is unlikely that AI-generated art will replace other forms of art making, and it will likely continue to exist alongside other forms of art making.

Overall, while AI technology and algorithms can be used to create interesting and novel artworks, it is unlikely that AI-generated art will replace other forms of art making. Instead, it is likely that AI-generated art will continue to exist alongside other forms of art making, as one of many different approaches that artists can take.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Do you think that AI art will get better with time?

It is likely that AI art will get better with time, as AI technology and algorithms continue to advance and improve. As AI algorithms become more sophisticated and are able to learn from larger and more diverse datasets, they will be able to generate more detailed and realistic artwork.

Additionally, as more and more artists begin to experiment with AI technology and algorithms in their creative process, they will develop new techniques and approaches that can help to improve the quality of AI-generated art. This could lead to the emergence of new styles and genres of AI art, and it could help to push the boundaries of what is possible with AI technology.

Overall, it is likely that AI art will continue to improve and evolve over time, as AI technology and algorithms advance and as more artists begin to experiment with AI in their creative process.

[ ↑ Back to top ]

Over its history, AI technology has frequently promised more than it could deliver. Is this the case with AI art right now?

AI technology has indeed often promised more than it could deliver in the past. However, this is not necessarily the case with AI art. While there are limitations to what AI technology and algorithms can currently do in terms of creating art, there are also many interesting and impressive examples of AI art that demonstrate the potential of this technology.

One of the key limitations of AI art is that it is currently unable to create art that is truly original and creative in the same way that human artists can. AI algorithms and technology are still limited in their ability to understand and generate novel ideas, and most AI-generated art is based on existing data and patterns.

However, despite this limitation, there are many examples of AI art that are impressive and thought-provoking. Some AI algorithms and technologies are able to create art that is highly detailed and complex, and there are many interesting and novel ways in which AI technology can be used to create art.

Overall, while there are limitations to what AI technology and algorithms can currently do in terms of creating art, there are also many interesting and impressive examples of AI art that demonstrate the potential of this technology.

[ ↑ Back to top ]