Roxanne Vardi

Daniel Belton is an artist, filmmaker, choreographer, and dancer from New Zealand. In 1997, Daniel Belton and creative producer Donnine Harrison founded Good Company Arts, an entity devoted to creating live events, exhibitions, and installations through the fusion of multiple art forms, and is internationally recognized as arts innovators that combines dance, choreography, fine arts, music, and digital cinema. Belton acts as the artistic director of Good Company Arts, and together their project based art programs are internationally recognized as innovating the arts and design sectors.

On the occasion of his solo show artcast Unification of Dance, we had a conversation with Daniel Belton about his work and artistic practice of combining different mediums and art forms into a unifying whole. Belton has choreographed a number of acclaimed dance works, created a number of experimental film dance works, and has created a number of short films. The artist holds a number of renowned rewards and honours.

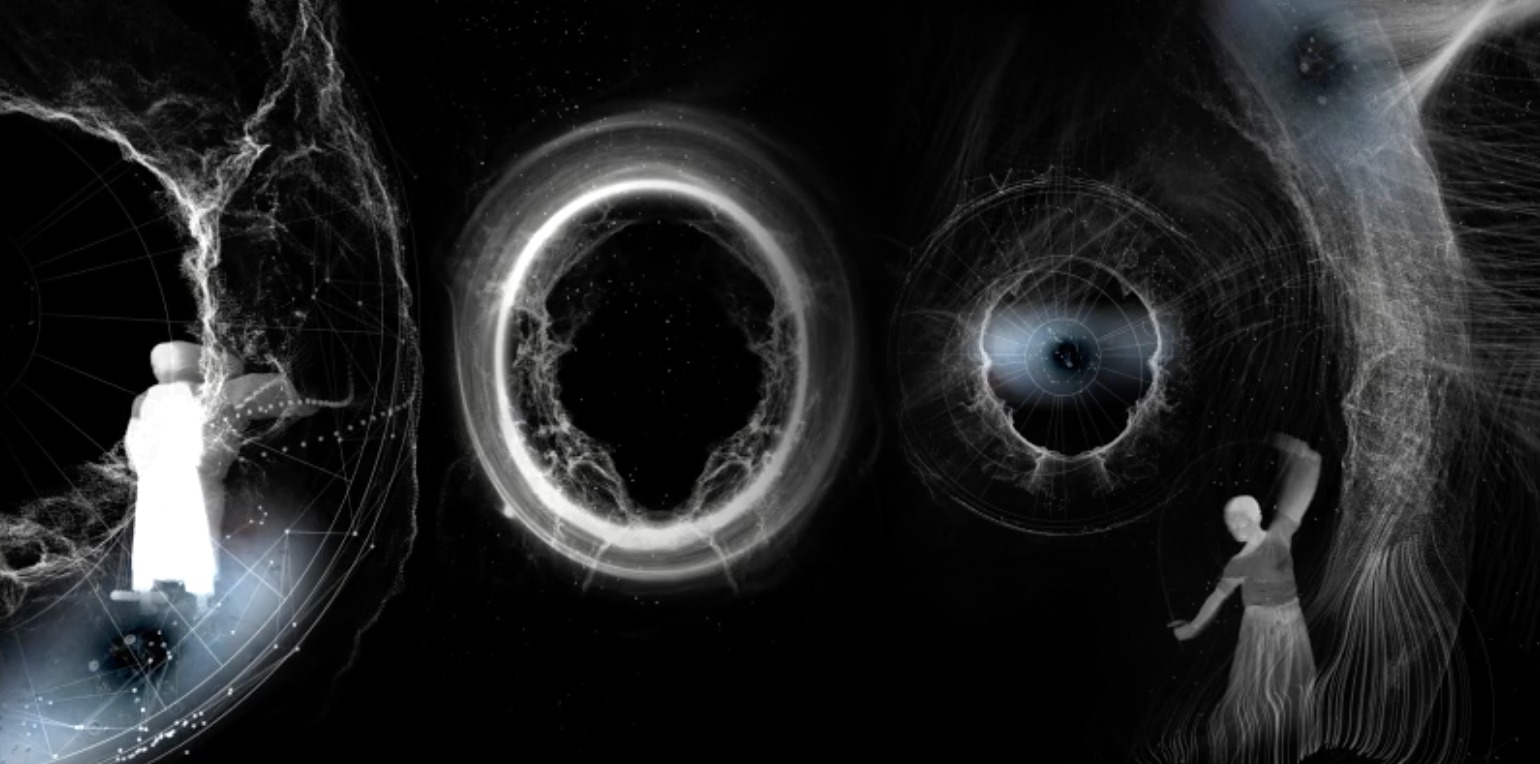

Daniel Belton, Astrolabe – whakaterenga (Portals), 2020.

In your digital artworks you combine contemporary dance, music, animation, and AV technologies. Can you walk us through the different complexities combining these disparate media into a coherent whole?

In my work the role of digitally augmented dance is really determining how the narratives or story threads are shared to the viewer. As well as this, the relationship between the choreographed work and music, is a central driving force. When you watch the works in motion, for me it is the relationship between the dance and sound, that is the heart beat, the emotional arc if you like. From this centre all the other elements are derived – the couture, the motion graphics and generative atmospherics, the virtual worlding of spaces in which the human figures project themselves, traverse, journey, or inhabit.

I’m a self taught filmmaker – I studied photography and painting before heading into an international career in dance. After a decade working in Europe for various theatre and dance luminaries, I returned home to Aotearoa NZ to begin raising a family, and this was is also a significant turning point, when we founded Good Company Arts (1998). I began working closely with film artists to initially document our live performances.

My curiosity for film and dance as shared mediums, really grew through the next decade, and continues to this day. More recently I have focused on outputs from the digital to print, and installations.

When I edit film, it is not in a conventional way. I use FCP, After Effects, predominantly for my workflows which often have 10 or more layers of visual material in a scene. I usually start by testing out the compositional space, with various visual components. This means playing with masks, scale, proportion, colour, and tone to establish a design language for the specific work. If you see all my works in a space together, you will recognise the “eye” and aesthetic, which is my signature. I’m grateful to the small team of collaborators who I bring in to support the overall vision – these artists work with software such as Cinema4D, After Effects, Premiere, Lightwave and more. I commission and guide their contributions, and we have a long rapport of collaboration. Their work becomes part of the total vision for the design feel of my work with GCA.

Collaboration with the performing artists is key. I work closely with Donnine Harrison (my life partner and Creative Producer for GCA), to choose dance artists who are also makers in their own right. These young artists bring their choreographic voices to the work, which is carefully guided. Usually we work shop and film in a choreolab style process. The filmed material is then reflected on in post, and this is where the relationship to music, and the visual design and narrative structure is developed – the total work is usually anchored this way. Sometimes later on, and it can be years later, a work is recommissioned to be performed as a hybrid piece. Then we bring the team together again to realise a performance activation of the digital work, for example with large outdoor projection, live music and live dance bridging to the digital world and expanding on it.

It is a fluid relationship. Works arrive and carry in a specific quality or message. They have their own energy and wairua (spirit). So the relationship becomes overtime, even more attentive because it is like communicating with a child of ours, and this is reciprocal. We listen, watch and respond.

“Works arrive and carry in a specific quality or message. They have their own energy and wairua (spirit).”

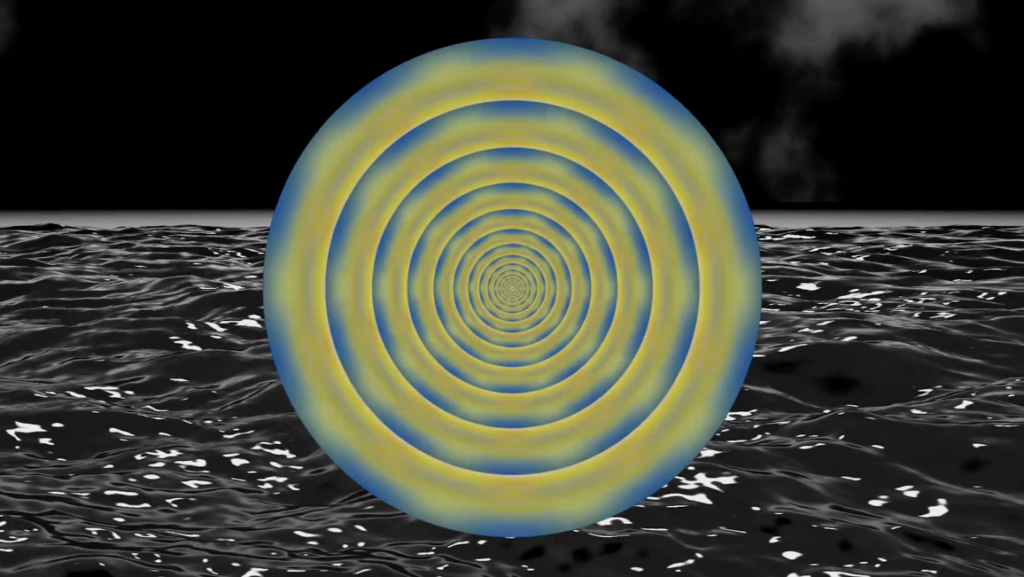

Daniel Belton and Good Company Arts, AD PARNASSUM – Purapurawhetū Solstice, 2022.

There is something very theatrical and cinematic about your compositions. Do you find inspiration in these two areas of artistic expression?

Yes, I come from a background as a professional dancer, choreographer and visual artist, with many years of working in theatres. It has become a deep fascination to explore how we can expand our storytelling practices out and away from traditional blackbox and proscenium theatres. This gradual shift in my own work, has developed skills with digital mediums to grow my practice for dance art-film, and 2D screens, projection mapping etc. More recently I’ve started the deep dive into XR which has migrated my projects with GCA from 2D to 3D formats with full dome and CVR.

To me, the theatre and the cinema are inherently connected. They are powerful amplifiers and channels for broadcasting our stories. Human beings are story telling beings. From the cave painters of the paleolithic, through to cutting edge VR, we have always pursued the liminal, pushed ourselves and our communities towards a greater understanding of our place in the cosmos. This search is a beautiful, ongoing quest for identity and belonging.

“Human beings are story telling beings. From the cave painters of the paleolithic, through to cutting edge VR, we have always pursued the liminal, pushed ourselves and our communities towards a greater understanding of our place in the cosmos.”

Daniel Belton and Good Company Arts, soma_songs_(aarhus_festival_promo) (Original), 2022.

Your artworks have been exhibited at art galleries, museums, public spaces, and architectural facades. Can you elaborate on the differences, at least from your personal perspective, working in the public sphere as opposed to the private gallery sphere?

This is about space, the human relationship to environment, our sense of belonging, and well-being. It is about discovery and returning to something to engage with it in a new way. What do we see? Our perception of an artwork is altered greatly when we augment through scale, light, surface. The ephemeral digital nature of film, especially projected, means that it is a membrane of datum, a digital cloak of light rippling with stories.

When we can identify ourselves in these stories because they are populated by the human in motion, then our awareness also moves to new places. So my works are not didactic, they do not attempt to tell a story in the traditional sense, rather to create an invitation for the audience to connect. This is a personal experience, and each individual will have their own response to an artwork.

I find that when filmed dance appears in unusual sites such as mapped onto building facades – people really engage with it. Perhaps part of this immediate connect is that dance is a universal language.

In this way we can bring a new kind of illumination to a site, and invigorate, catalyse. For my work Line Dances at the Bauhaus University in Weimar, this was a direct link up to Paul Klee’s lithographs inspired by the theatre such as his delicate and humorous “Realm of the Curtain” and “Equilibrist”. It was 2013 with the Genius Loci Weimar Festival, and my first go at projection mapping. Since then we have learnt much, and I have been fortunate with GCA to be invited to many cities to show our work in more unconventional ways, with mapping.

I do love the clarity and purity of a fine gallery or museum space. Artwork can breathe, and when curated well, bodies of work offer incredible insight to public, around an artists practice and oeuvre.

Many of your artworks, including Astrolabe – whakaterenga (Portails), are rendered in black and white and display celestial, astrological compositions. Could you elaborate on the intended reception of these representations?

The monochromatic space is powerful. I find it a natural optical realm in which to create compositions, and to cultivate spatial relationships that are coherent. Integrating the human figure here is also a natural progression for me. Don’t get me wrong, I adore colour! But it must be introduced carefully and deliberately. Human beings are travellers, and our ancestors were largely nomadic. Since we can remember our species have navigated using the stars, and the natural elements which we embrace as part of the vast family of sentient life on Mother Earth. In our shared histories, Indigenous peoples from all around the globe have created maps and charts, and systems to move safely and efficiently from place to place, over land and water. Everywhere we look, there is evidence of knowledge founded in the wisdom of the stars, and the wisdom of living in rhythm with Gaia (Papatūānuku). Certain GCA projects I have directed, such as Astrolabe – Whakaterenga, are about celebrating this. Whakaterenga in te reo translates as “to launch”. In this work, there is a merger of Asian and Pacific Island wisdom, that binds such systems as astronomical charts and stick charts (used in canoes to navigate with the stars). This work as with OneOne is about honouring diversity, and acknowledging the many links that bind us. These pieces are affirmations of the human spirit, of diversity and unity. They speak of the interconnectedness of being.

Daniel Belton, NGURU, 2022.

In many of your works, including NGURU, you reference Māori arts which are an important part of Māori culture. Could you dive deeper into this compelling subject matter and how it facilitates in representing more contemporary media?

In some of my works, those that carry and promote nga taonga pūoro, I have with GCA engaged Māori artists who are practicing musicians, composers, dancers and weavers. Specifically the works are OneOne, Taiao, Astrolabe, Nguru and Ad Parnassum. Although I am not Māori, I have Maori and Samoan cousins. I greatly respect and admire Māori language, arts and culture. When GCA brings in Māori artists to collaborate, they lead in their specific field of expertise, and their mahi (work) is carefully combined into the total artwork and process. We are attentive to protocols (tikanga) and this is reciprocal. For Ad Parnassum -Purapurawhetū there is a focus visually on weaving and the horizontal. The music score created by Dame Gillian Karawe Whitehead (of Ngai Terangi and Tuhoe descent), is a fusion of classical (string quartet) and taonga pūoro (traditional Maori instruments). Of the nine female dance cast, 2 are tangata whenua (which means they are Inidgenous Māori, or have a Māori bloodline). The other 7 dancers make up this multi-cultural team which combines ancestry from Japan, India, the Phillipines, Eastern and Central Europe, Scandinavia, and Fiji. Their dance is contemporary, not traditional, but I do see influences in their work that offer glimpses of each artists cultural ties.