By Pau Waelder & Roxanne Vardi

Snow Yunxue Fu is an artist working primarily with 3D software in a post-photographic framework creating experiences of experimental abstraction for her viewers that translate the concept of liminality into the digital space. She is also a curator and assistant professor at NYU Tisch school of the arts.

Fu’s practice combines historical and philosophical painterly explorations of the universal aesthetic and definitive nature of the techno sublime through topographical computer-generated images and installations

Following the release of two new artworks commissioned by Niio recently featured in our curated artcast Snow Yunxue Fu: Liminality we spoke with the artist about her art practice and her exploration of the techno sublime experienced through the digital space.

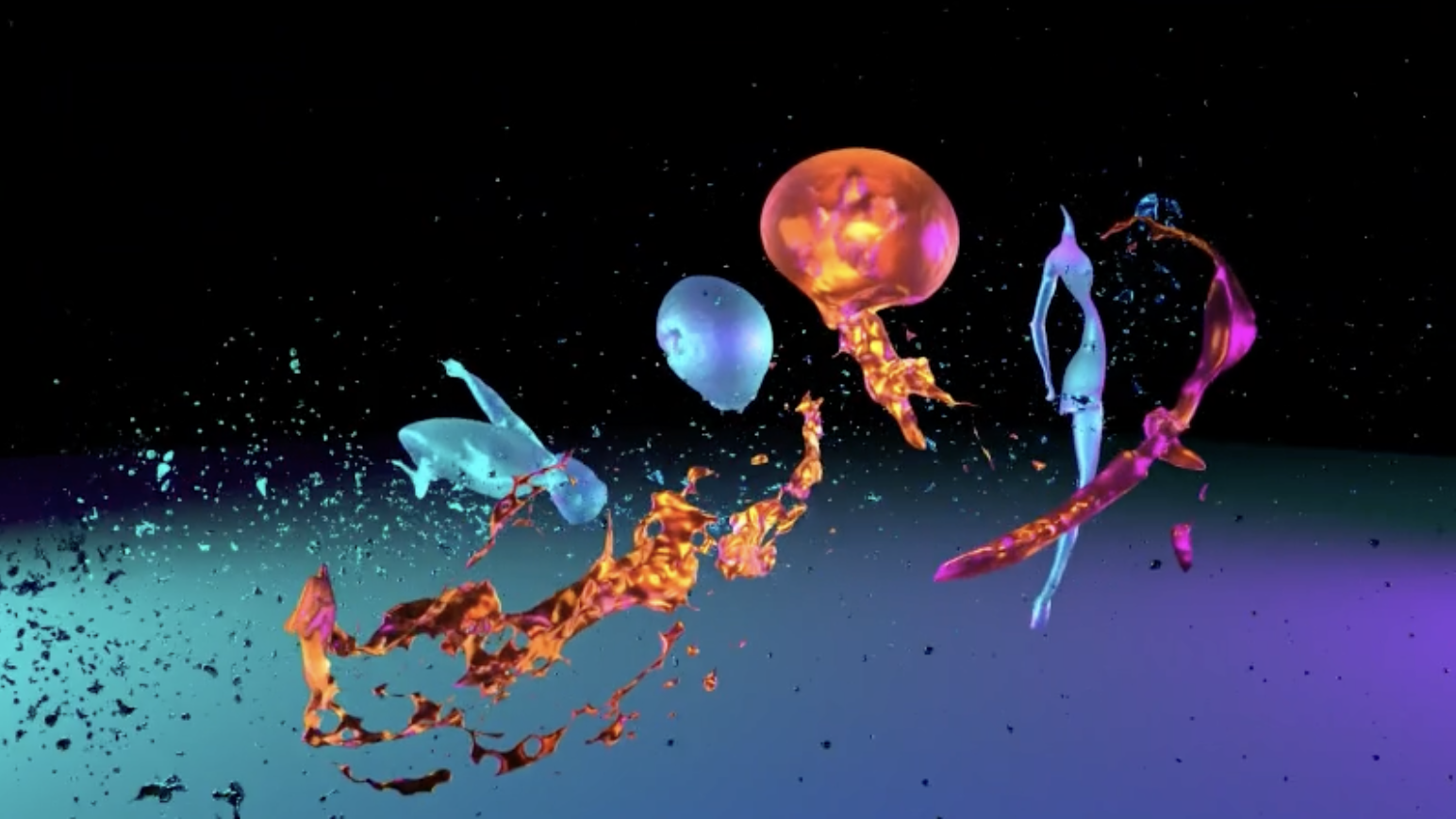

Your work, Resolution, initially displays a human-like form which turns into a liquid matter and is later shattered into small particles accompanied by a pulsed sound wave. Would you consider the reference to human creation as present in this work?

Yes, definitely, I think one of the reasons why I was very interested in working with fluid simulation in 3D was this idea of manipulating water. Water, in the physical world, is such an important element. Relating to this piece, human bodies are made in a high percentage of water, and I think of the way that kind of occupies our veins and our different organs. It is this idea that in everyday life, moving around, we think of the human as one entity. When I was studying oil painting, what was really interesting to me early on was the notion of the figurative as representational instead of abstract. But to me, I think there is so much abstraction, even when we are seeing inside of our body. So the work kind of came out of that, in a way, this idea of forming the human body, which is something that we recognize immediately, but then kind of breaking that into millions of pieces, so to speak, to refer to the number of small components that make up each one of us. That also still changes every day as our cells regenerate. The birth of a human being too is very much that, but conceptually too, even within the physicality of ourselves there is this subliminal quality which is sometimes hard for us to remember.

There is also an element in the work that speaks of the separation between what is nature and what is human-made. Many different cultures maintain this division, but really there is this idea that even our very own atom was once out in the universe. Technologically, in contemporary culture, we feel that we are the center of the world, but in the scale of things we are just a very small part. This matter exchange is definitely also part of the work. The water that we drink was once a part of a river and so forth.

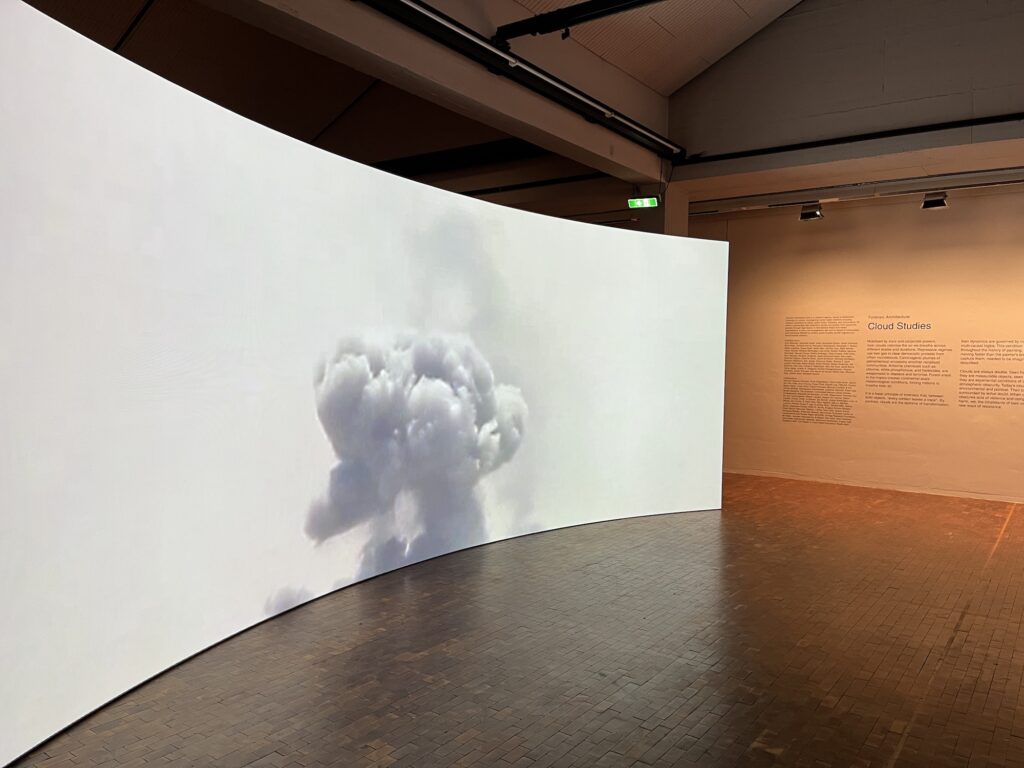

Snow Yunxue Fu, Resolution, 2020.

You have often pointed to the Sublime represented in classical paintings to portray transcendent physical landscapes as a reference in your new media artworks. How do you relate the art historical use of the Sublime to virtual spaces?

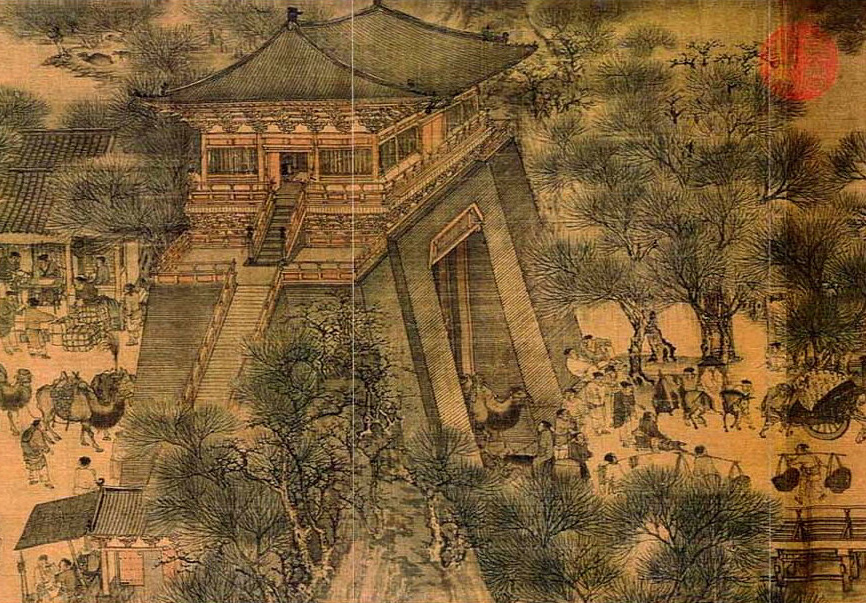

I first encountered the idea of the sublime in classical paintings with Caspar David Friedrich, who is this very iconic figure. But then there was also this very personal experience for me, it’s actually something that always interested me, even as a very young person. I come from the inland of China, so I didn’t see or experience the ocean at a young age, as this is a very unique experience for inlanders. So when I finally did there were these moments when I thought that ‘the ocean is so big’. Also, I created a VR piece that I made in 2018 of a cave, that was actually another experience I had when I was five years old, where I went into one of those Karst caves. This is when I realized that all of the rocks are actually made out of calcium and salt accumulations and water again. I had this sort of physical reaction where I was simultaneously fascinated by how beautiful everything was and the kind of concept that this rock existed long before me and will exist long after me, but then I was simultaneously also scared to death as a five year old little girl. I think this combination that anything could fall on me or that water could rise enough so that I couldn’t get out was terrifying. What I was experiencing was a memorable experience of my own mortality. Relating that back to paintings and to art, I kind of picked that up from Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings. In a sense, he already depicted the broadness of the environment, but honestly, the pictorial frame is still very limited. So when I understood that I could do this with VR, I jumped on the opportunity. With a lot of Eastern Chinese landscape paintings, the way that human figures have been depicted, is such tiny scale compared to the vast mountains, which is many times a lot less about the perspective compared to Western oil painting, and more so about our experience and place in the world.

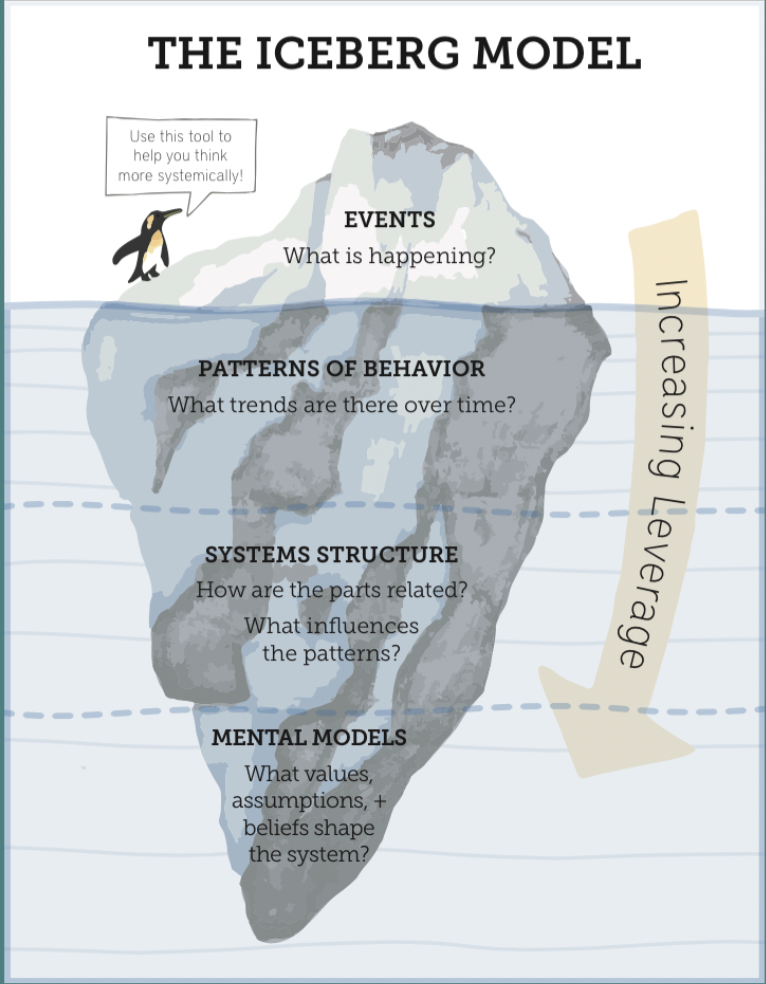

So I drew that connection to these historical gestures of trying to find one’s place in the world or kind of humanity’s place in the world in terms of scale. Earlier I mentioned that technology, especially digital spaces, kind of give me this very strong visual language to be able to kind of depict that vastness. So, I just kind of jumped into that counter effort to push against that idea where online culture makes us feel like we are the central attention of the world. Another group of artists that I relate to is the Land Art Earth Work group of artists from the 1960’s and 70’s. These artists went right out into nature, and created artworks that were kind of ephemeral. Like Andy Goldsworthy, who sometimes brought back natural elements into the gallery museum space as installations. In a sense, I feel like my practice relates to that as well, where the digital space becomes a mirror of the physical world. Even the vast cave that I made is really a very small model, so I think of my digital work being sort of this theater space, of what is happening out in nature. But of course, there is also this imaginary aspect that landscape or water is so hard to control. It takes different technologies and different sorts of machines for us to do this, but at least with simulation, the imagery of it becomes something that we can control such as waterbending. So there is that interactivity which is almost imagined because it only happens in the digital space, but it’s this desire for the fluidity, or a highlight of this underlying connection that we have to the larger world that is already going on. Mentally there is immersion with digital artworks. 3D or digital works can be considered epistemological models of the world. There is so much wealth of knowledge of how things work. Once we gain that knowledge, the question should be ‘how do we coexist in harmony?’ Since we are doing a lot of harm, we should ask ourselves what some of the ways are to live in harmony. That is a main question in my work.

“I drew that connection to these historical gestures of trying to find one’s place in the world or kind of humanity’s place in the world in terms of scale.”

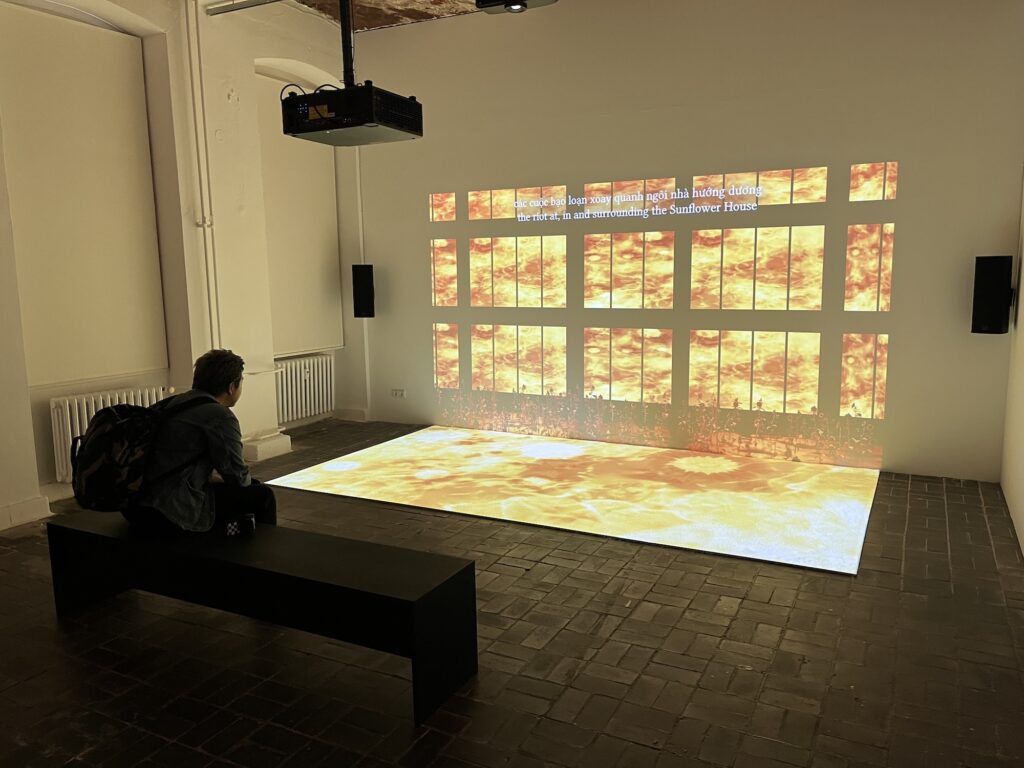

Snow Yunxue Fu, Karst, 2019.

The experience of the Digital Sublime can bring up emotional responses which are either utopian or dystopian. Do you have a preferred response which you wish to relay to the viewers of your artworks?

This question is very efficient in terms of talking about the subject, the setup of utopia and dystopia, and the liminal. For me it’s something in between. I am frequently also asked whether I am in favor of the digital space completely taking over. I am not necessarily for this, the digital space really has vast implications, 3D simulation is a huge part of our life, so what this space can present to us again to me is this kind of mirroring or window-like looking out of what is possible within our immediate understanding. To me that is the reason why I am interested in depicting the Sublime in the digital space, it’s that simultaneity. I have also recently been working on projects where I create web3, Metaverse spaces, but I think that they exist because of the reference or relationship that they have with the physical world. So, technology can be used for very interesting and strong messages, but can possibly also be used to create damages and for these dystopic-like reasons. The way that I want my viewers to experience my work is to understand the simultaneity, it’s kind of a feedback loop of seeing the work, which helps us understand what is physical. So they don’t even necessarily kind of separate these any more, but it’s a fruitful way for us to gain more understanding. Nevertheless, I think there is certainly a huge possibility of dystopic implications.

“The way that I want my viewers to experience my work is to understand the simultaneity, it’s kind of a feedback loop of seeing the work, which helps us understand what is physical.”

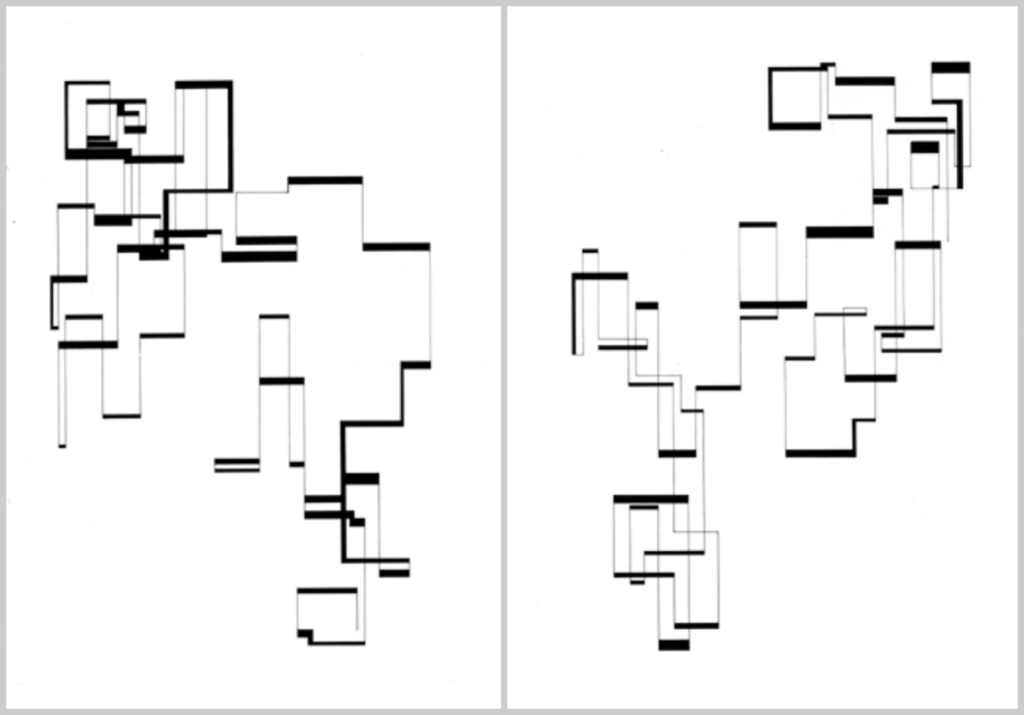

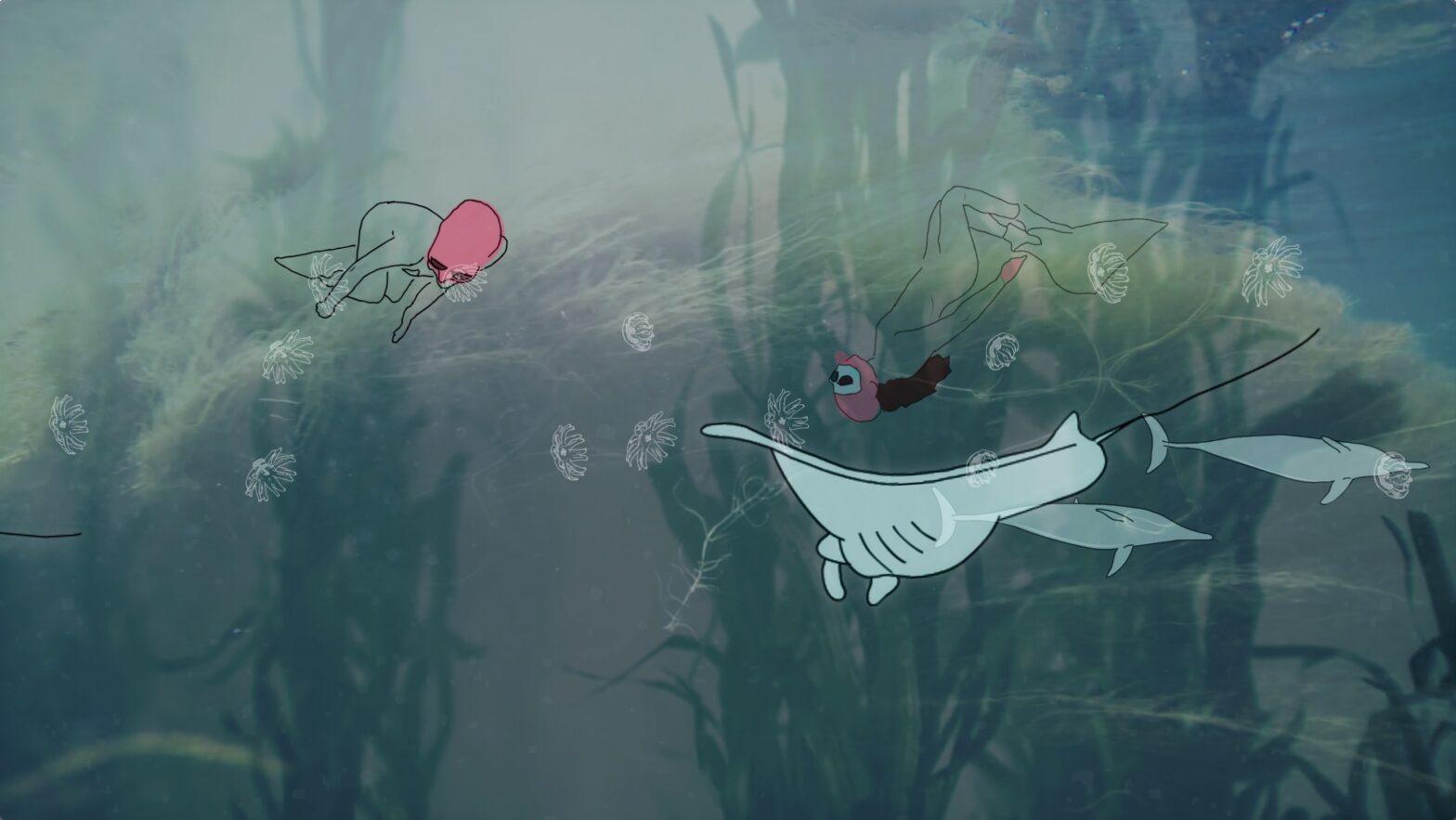

Snow Yunxue Fu, Conjoin (Chapter 3), 2020.

Both your works Resolution as well as Conjoin portray to the viewer experiences of deconstruction and reconstruction turning the at once seemingly figurative shapes in the works into abstract elements. Would you consider this to be analogous to the human experience between the physical and the virtual worlds?

Yes, totally. I think maybe another aspect to be brought into this dialogue which we also discussed earlier is the limitation of human perception. So there is a lot going on, whether we kind of study it via science, philosophy or any other sort of discipline. We try to sort of understand that something that is beyond what just meets the eye. As human beings we are really interesting, because we not only understand a concept in our brain but we are sensory beings. We can travel or go somewhere and once we are there we can experience things such as the air, the smell, and everything else, which is crucial. But then simulation is interesting too, especially the direction in which this technology is going. There are actually also simulations of sensory, which is being promised and introduced now. So that it’s not only what meets the eye and the ear, but in the future we will be able to wear gloves and to touch a surface that is for example supposed to be perceptually cold, or hot, or sharp or smooth. So, I think the translation again here is really fruitful and meaningful. This is one of the reasons why it attracts me so much to create works in this space. What I am sort of dreading in a way is that kind of space of open-endedness which gets formulated by big social media companies such as Meta. Right now what one artist can do is still very exploratory. I think that that is valuable, to protect that open space instead of having the Facebook version of what the Metaverse will be, which is probably what we don’t really want.

Could you elaborate on the concept of liminality in the digital world?

For me, the interest in terms of liminality in the digital world was always there. The way that I was able to corner it in my own practice, was when I looked into the work of Anthropologist Victor Turner. His research of the liminal and the liminoid helped me with the verbal language, to try to paint a faint picture of what I was trying to talk about. Turner defined liminal as change, periods of in-between changes so that you are not where you used to be, but you are not yet where you will be in the future. So, it’s the middle stage of a rite of passage. Liminoid is slightly different, it is a more playful and experimental space, less of a consequence, with the liminal things will change, there is an outcome. But the more you look into it the boundary blurs. For example, one can go about their everyday business, or go to a football game, and cheer, but this will not necessarily change the outcome of the game. The blurring of the lines breaks down very easily also when you are playing a video game, where you step in, play a role, and then you step out. We enable different versions of ourselves online, we choose to reveal as much as we want. The Internet can be an intimate space. But, one could also have a complete other version of themselves online. Most of us are in between both extremes. Liminality to me is that complicated relationship that one has with that. It’s a transformative experience. When we think of a transformative experience, we think of an incident that happens really fast. There is also the way that the internet changes us individually and as a society as a whole. The pandemic catalyzed that even more so. There is that societal change, but what I am interested in, which is not the common narrative that people connect to online spaces, is that this could be an opportunity for us to discuss, dive into, and interact and have a more authentic understanding of the world. A window of opportunity to reveal what cannot be seen by the eye, in this sensory way. This is what liminaility means to me, that back and forth force.

In the physical world there are many cultural and societal rules. The introduction of Zoom was a positive experience for me, as for a while the hierarchies that we were used to seeing in the physical world such as the human body changed. Personally, I am a small person and come off as very young, thus people usually project a certain way of talking to me. But when everyone was meeting online, especially during the pandemic, we all became squares. This disrupted the hierarchy which is very hard to break, which is a positive example of disruption. To reference Resolution, I think that there is so much more communality in humans that we have with each other such as our DNA and our molecules. This fundamental connection helps me to relate to a value system where we should all be treated equally. This possibility of a new configuration arises with the metaverse, that’s why the metaverse is portrayed in a utopian way. The potential of the unknown is what I am interested in, coming back to liminality, it’s not formulated yet, it’s open, we are listening to each other and trying to understand what humanity is all together.