Pau Waelder

Kunsthalle Praha is a new contemporary art space that opened its doors in February at the former Zenger Electrical Substation in the heart of Prague. Founded by the Pudil Family Foundation, it aims to connect the Czech and international art scenes through a varied program of exhibitions and events that take place both in their physical location and on their website, in the form of a “Digital Kunsthalle” that collects video documentation, articles, and digital guides to the exhibitions. The use of the term Kunsthalle identifies this institution with the focus on temporary exhibitions as opposed to hosting a permanent collection, which is nevertheless built through a program of acquisitions and will be presented to the public regularly in thematic exhibitions and in a digital catalogue.

Given Kunsthalle Praha’s foundational aims and the history of its building, it is only fitting that the inaugural exhibition is dedicated to the role that electricity has played in the development of art over the last century and up to the present. Kinetismus: 100 Years of Electricity in Art is an ambitious group show spanning a century of artistic creation through a selection of nearly a hundred artworks that connects the avant-gardes of the 1920s with the pioneers of kinetic and cybernetic art, and today’s digital art. Curated by Peter Weibel, revered theoretician, artist and director of the ZKM in Karlsruhe, alongside Christelle Havranek, chief curator at Kunsthalle Praha, and scientific associate Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás, the exhibition’s curatorial concept is centered around establishing the legacy and relevance of electronic and digital art in contemporary society (an approach for which both Weibel and the ZKM are widely known) as well as cementing its position in the history of modern and contemporary art. In the text he wrote for the exhibition’s catalog, Peter Weibel denounces the lack of attention that digital art has received from the contemporary art world and its institutions:

“Most museums still refuse to include light art, sound art, interactive art, and cinematographic, cybernetic, or computer art as part of their collections or permanent exhibitions. It could be called a betrayal of the masses since such museums are not truly exhibiting the art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries but rather only paintings and sculptures from these centuries.”

Weibel, 2022, p.36

These strong words express the frustration of more than one generation of artists, scholars, curators, gallerists, collectors, and also art lovers who have seen over and over again how artistic practices linked to scientific disciplines and technological innovations have been sidetracked or utterly ignored in the mainstream contemporary art world, in which even photography and video have struggled to gain recognition as art. While this situation is clearly changing in recent years, there is still work to be done, not only to integrate digital art in the contemporary art scene, but also to understand its nature and history.

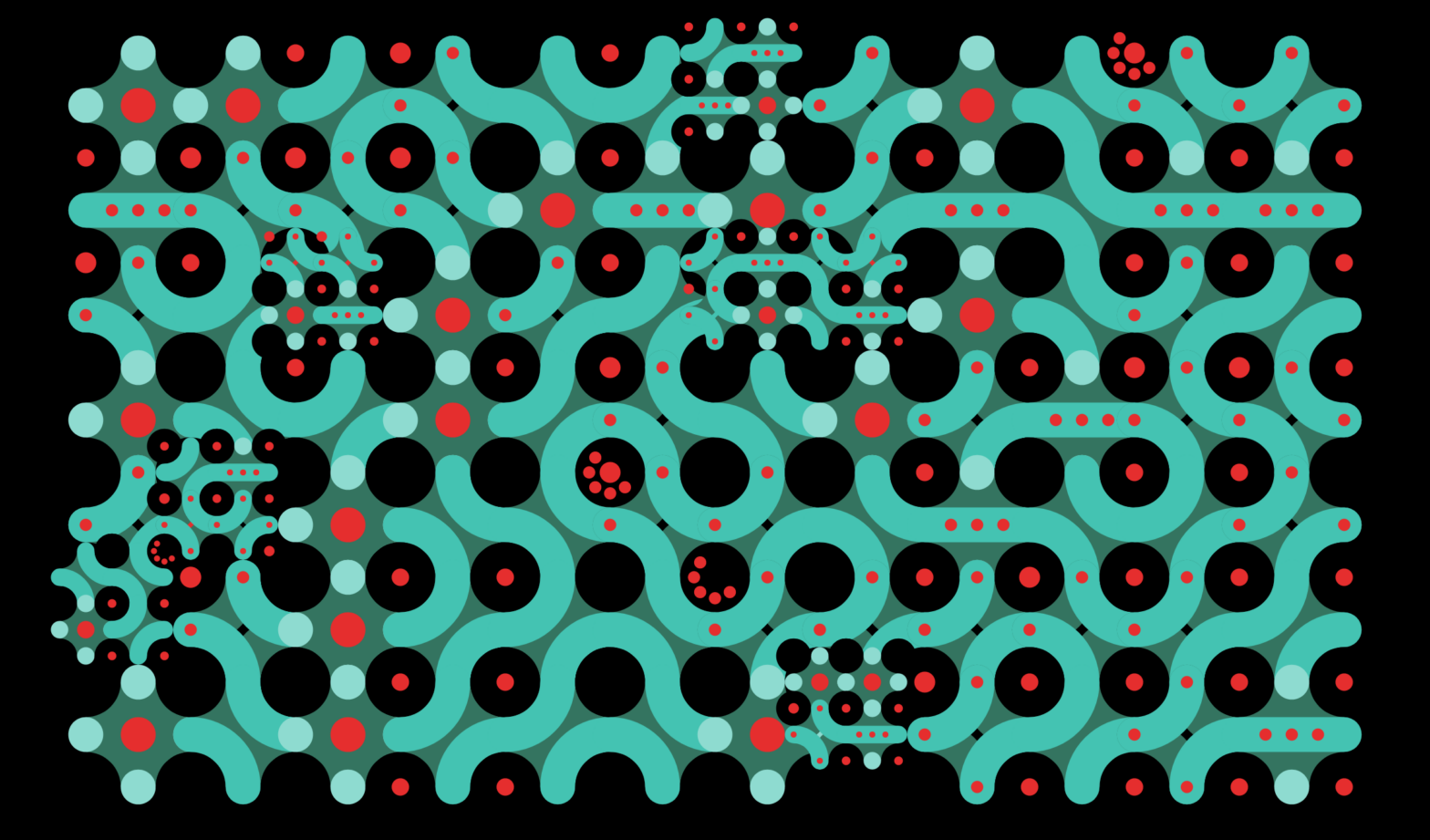

Kinetismus both adheres to the sober presentation of historical artifacts that is required of a museum, and the playful experience of visitors in front of a series of artworks based on ongoing processes.

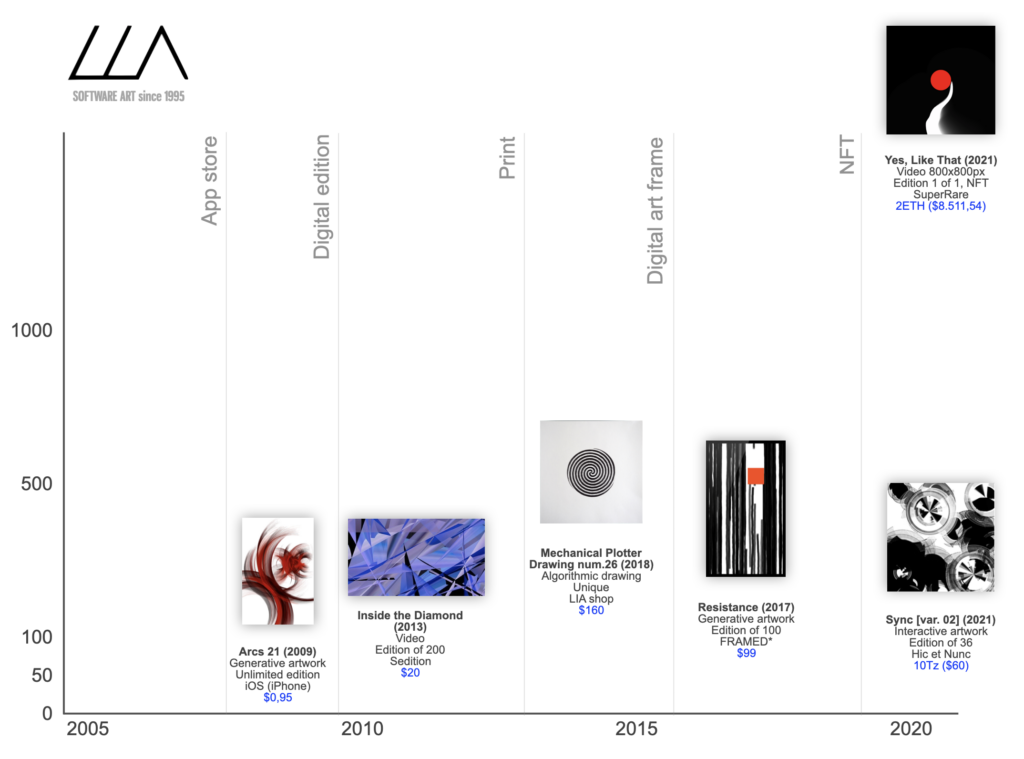

The NFT boom brought a renewed attention to digital art and consequently its history, although the crazed search for “OGs” has finally lead to the artworks of pioneers being used to attract newcomer collectors and boost sales at auction. It is therefore more necessary than ever to present the history of digital art to the public in all its manifestations and its complex ramifications, not only to bring attention to the names of those trailblazing artists who had been partly or almost totally forgotten, but also to better understand how the artistic practices linked to electronic and digital media came to be. Kinetismus aptly carries out this task in a way that both adheres to the sober presentation of historical artifacts and the information around them that is required of a museum, and the playful experience of visitors in front of a series of artworks based on ongoing processes rather than static objects.

The Four C’s: putting digital back into art

Peter Weibel points out that a singular trait of the exhibition is its aim to highlight the existence, for the past one hundred years, of an art based on electricity (“plugged-in art”) that he describes as “the predominant singular achievement of the twentieth century” (Weibel, 2022, p.36). Interestingly, this all-encompassing denomination overrides the myriad terms used to describe artistic practices based on emerging technologies since the work of the pioneering creators of algorithmic plotter drawings was described as computer art. It also connects these practices with the history of modern art, going back to avant-garde experiments with light, movement, and cinema. In this sense, the curatorial approach finds yet another form of integrating digital art into a long tradition of artistic practices that are already part of the established canon of modern and contemporary art history.

Since the earliest experiments integrating emerging technologies into artistic projects, artists, theoreticians, and curators have sought to highlight the distinctive features of these art forms while making it clear that they belong to the fine arts, namely by establishing links and comparisons to painting and sculpture. From the seminal texts of artists such as Lászlo Moholy-Nagy in the 1920s, to the essays by theoreticians and curators such as Jack Burnham, Jasia Reichardt, Frank Popper and Herbert W. Franke in the 1960s and 1970s, to name a few, connections have been constantly drawn between art, science, and technology, seeking to expand the notion of what art is and how it relates to a society that is increasingly dependent on the technology it has created and shaped.

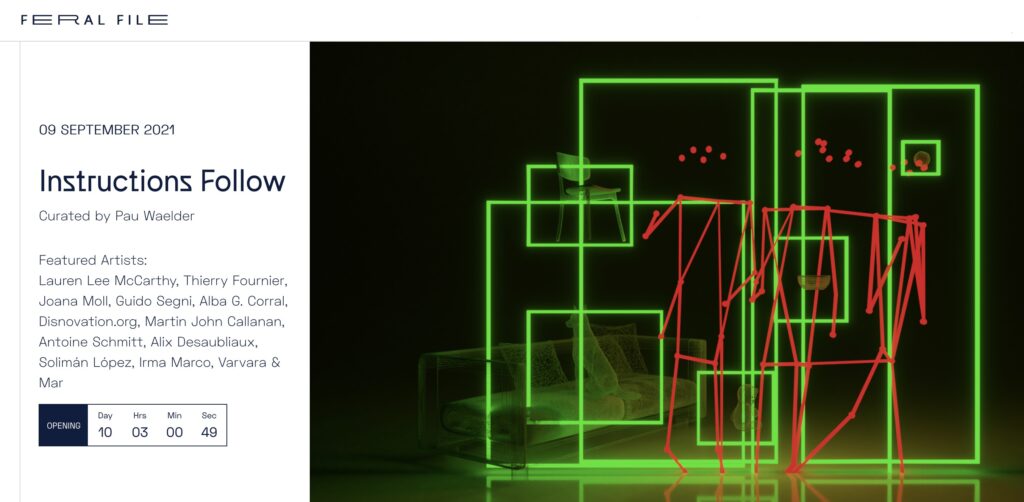

Weibel stresses that the structure of the exhibition according to the “Four Cs” (cinematography, cinétisme, cybernetics, computer art) is what makes this exhibition different than other historical reviews of electronic and digital art

The field of what has been variously termed computer art, cyberart, electronic art, new media art, or digital art has evolved over the last sixty years into an art world of its own, but it has always been conceived by its proponents as part of the wider field of contemporary art. During the last decade, an increasing number of books and art exhibitions in museums and art spaces have underscored the connections between digital art and the history of art in the twentieth century. These approaches have been based on a concept or feature that can be traced in both digital and analogue artworks, such as the use of light, movement, instructions, or the participation of the audience.

For instance, in 2009, art historian Edward Shanken proposed in his book Art and Electronic Media (Shanken, 2009) a history of digital art based on a series of “thematic streams” such as “Motion, Duration, Illumination” or “Charged Environments,” that allowed him to connect the work of avant-garde pioneers such as Moholy-Nagy with that of established artists in the digital and contemporary art worlds such as Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and Olafur Eliasson. Similarly, in 2018, curator Christiane Paul presented alongside Carol Mancusi-Ungaro and Clémence White the group exhibition Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965-2018 at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, which drew on the concepts enumerated in the title to bring together works of video art, generative art, and conceptual art spanning more than fifty years.

Kinetismus similarly establishes thematic connections between kinetic art, cybernetic art, experimental cinema, and digital art (here presented under the term “computer art”), as well as dialogues among the artworks exhibited at the Kunsthalle Praha. Weibel stresses that the structure of the exhibition according to the “Four Cs” (cinematography, cinétisme, cybernetics, computer art) is what makes this exhibition different than other historical reviews of electronic and digital art, as it allows for a rich spectrum of associations, correspondences and interplays between artistic practices that have often been considered as separate approaches to artistic creation.

Certainly, the dependence on electricity to power light sources and motorized elements in kinetic artworks, cameras and projectors in experimental films, and computers in all sorts of digital art is a common factor to all of these art forms. This leads to two main elements that depend on electricity and ultimately connect all of the artworks in the exhibition: artificial light and movement, the latter more widely understood as a permanently ongoing process, as opposed to the static object that is a painting or a (classical) sculpture. To properly map all these connections and describe the artworks in this article would be a futile effort, as the texts written by Weibel, Havranek, and Nolasco-Rózsás for the catalogue already address the “Four Cs” in detail, and additionally a wealth of information about the artworks can be found at the exhibition’s digital guide, freely available online. Instead, I will focus on two differentiating aspects of the exhibition which are particularly relevant to the presentation of “plugged-in art” to the public: the attention to local and national art scenes, and the experience of the visitor.

The legacy of Zdeněk Pešánek

While the digital art community has often criticized the contemporary art world for sidetracking or ignoring them, the history of digital art has been built mainly around artists and exhibitions from Western Europe, the United Kingdom, and particularly the United States of America. The blind spots in this history, which is still being written, are being addressed by artists, scholars, and curators from different nationalities who are enriching the knowledge about pioneering artists from Latin America, Asia, and other regions of the globe. In this sense, it is important that historical reviews such as the one proposed by Kinetismus pays attention to the contributions of their own pioneers.

The Prague show is structured around the work of Czech artist Zdeněk Pešánek (1896-1965), a painter, sculptor, and architect who was among the first to create light-kinetic works in the 1920s and the first to use neon light tubes in an artistic installation. He built the Spectrophone (1924-30), an instrument composed of a piano that projected moving lights onto a relief, combining music and visual kinetics. This machine would be the basis for his light-kinetic sculpture Edisonka (1926-30) at the Edison Transformer Station at Jeruzalémská street in Prague, which became a fundamental artwork of this period, alongside László Moholy-Nagy’s Light-Space Modulator (1922–30). Later on, he created the series of sculptures One Hundred Years of Electricity (1937) for the façade of the Zenger Transformer Station, which were exhibited that same year at the International Exposition of Arts and Technology in Paris. Most of the sculptures were lost on their return trip, the series never being installed at its intended location.

The 3D illustration created by Studio Najbrt reinterpreting one of the artist’s sculptures makes Pešánek’s work vibrantly alive and up-to-date, more post-Internet than 1930s avant-garde.

As stressed by Christelle Havranek, Pešánek’s groundbreaking work did not receive the attention it deserved at a time when the rivalry between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany prefigured a global conflict that had already started its dead toll in Spain, as denounced by Picasso’s masterpiece Guernica (1937). Pešánek nevertheless continued his investigations and coined the term “kineticism” in his book Kinetismus from 1941. The repurposing of the Zenger electrical substation as the Kunsthalle Praha naturally led to conceiving an inaugural exhibition around electricity in art in which Pešánek’s work and ideas take a central role. In this respect, Havranek points out that it was not their aim to review the artist’s work (a task already carried out in a retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Prague in 1996) but to place it in the larger context of the international art scene, spanning from the early decades of the twentieth century to the present.

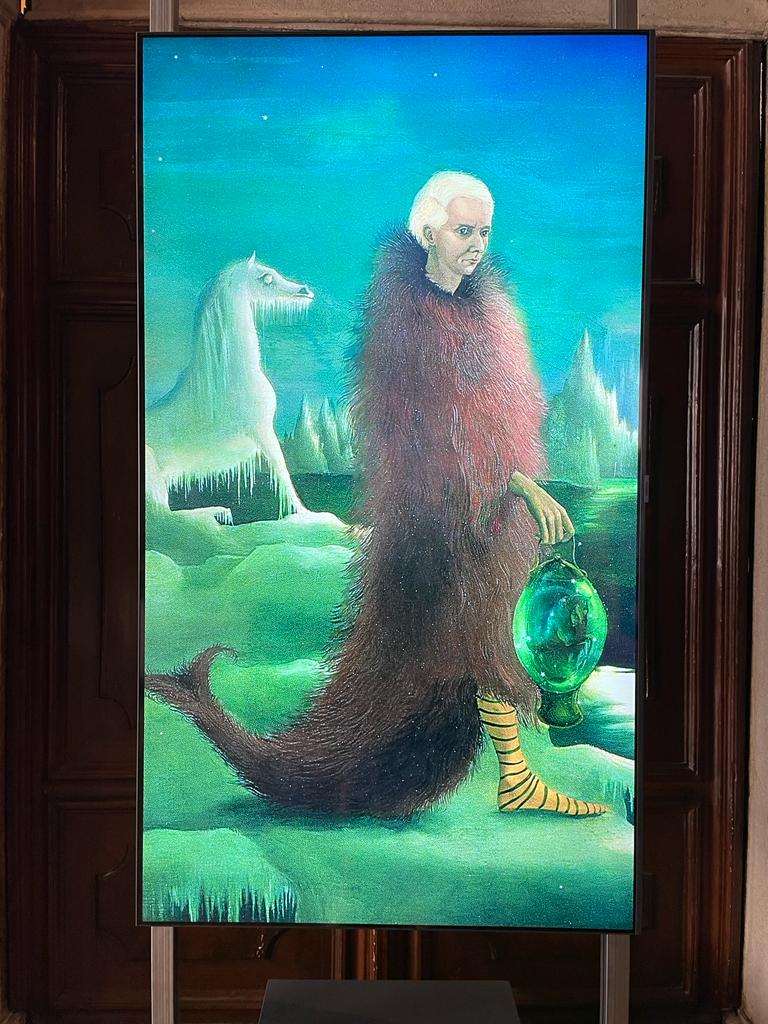

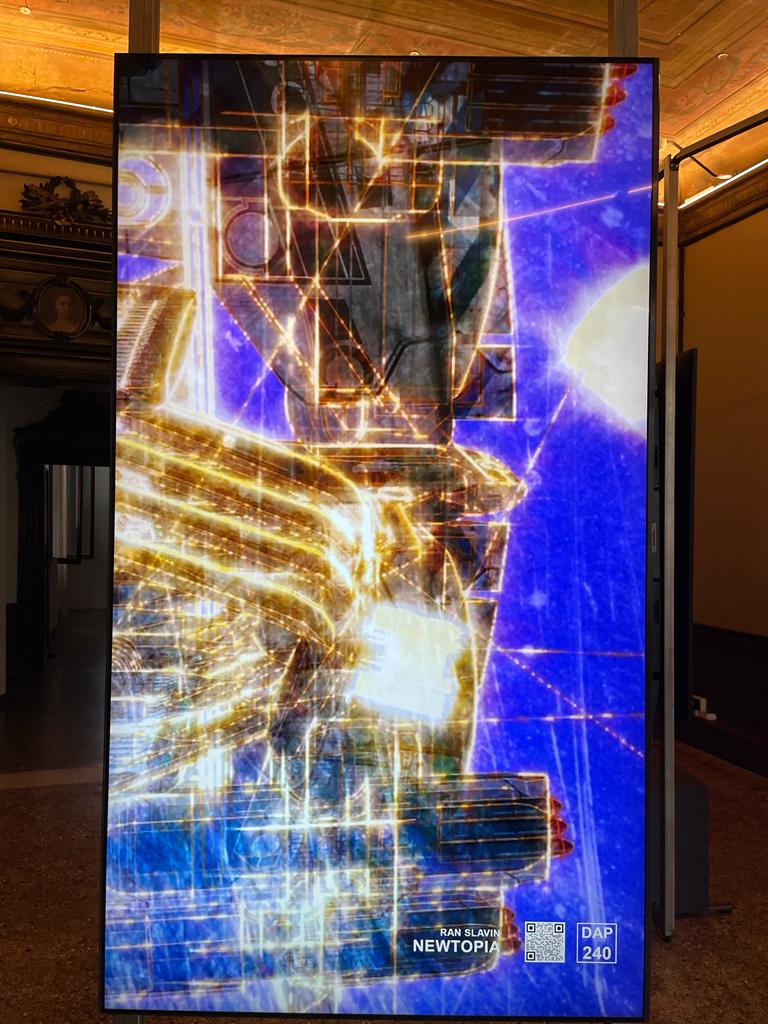

Several pieces from One Hundred Years of Electricity (1932-36) and The Spa Fountain (1936-37) are exhibited in the first gallery of the Kunsthalle alongside artworks by his contemporaries Naum Gabo, László Moholy-Nagy, and Marcel Duchamp, as well as kinetic art luminaries such as Julio Le Parc, pioneers of digital art such as Lillian F. Schwartz and Jeffrey Shaw, established names in the contemporary and digital art scenes such as William Kentridge, Olafur Eliasson, and Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau, and young talents such as Anna Ridler. This juxtaposition of artworks from such a wide temporal range reinforces the relevance of Pešánek’s work, considered in its historical framework, but probably more importantly it is the 3D illustration created by Studio Najbrt for the exhibition poster and the catalogue cover reinterpreting one of the artist’s sculptures what makes Pešánek’s work vibrantly alive and up-to-date, more post-Internet than 1930s avant-garde.

In accordance with the general conception of the exhibition, the combination of a serious, properly documented approach to Pešánek’s artworks and their history, and a playful reinterpretation that takes over street billboards and is able to communicate with a wider and younger audience constitutes a sensible decision that should be common to all presentations of the history and the present of digital art.

Enjoying kinetic and digital art

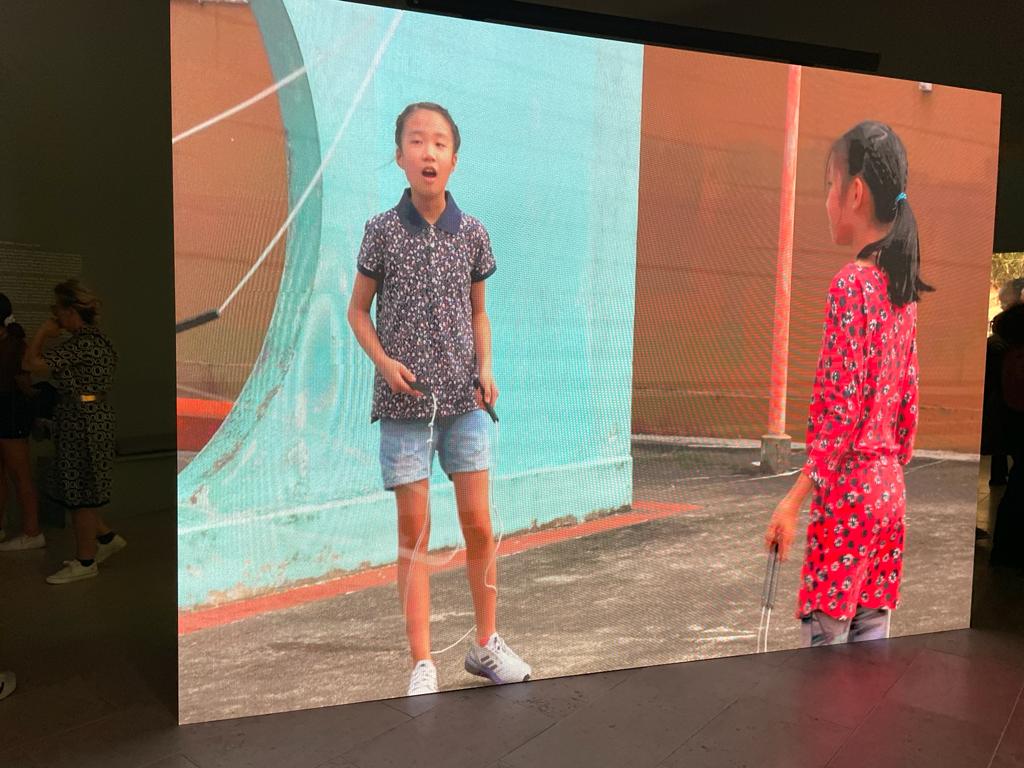

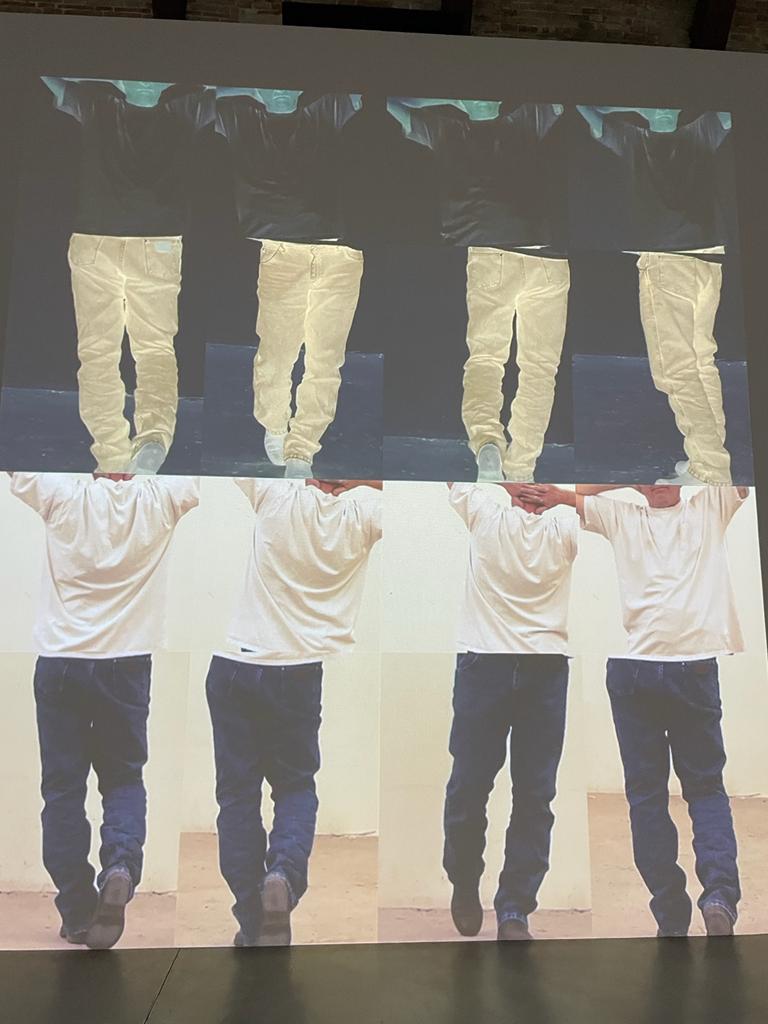

Not everyone wants to read a long theoretical text before approaching the artworks at an exhibition. Some prefer to simply experience the artworks, and while it is true that one cannot expect to fully understand an artwork without some context or explanation, there is a strong value in this direct, unmediated exposure to the art. In Kinetismus, the exhibition space, particularly in the first gallery, involves an interesting contradiction: the room feels crowded, there are artworks everywhere (almost fifty in a space the size of an average art gallery), emitting noises and projecting light and reflections on each other. The initial impression is somewhat chaotic, but at the same time it reminds of early exhibitions of kinetic and electronic art from the 1960s and 1970s (which, I must say, I have only seen through documentation). The studio that designed the exhibition space, Schroeder Rauch, consciously aimed to create a “multi-perspective and dense exhibition,” in which “the artworks but also the visitors find themselves in an open landscape environment of objects, movements and light. Everything is in communication with everything.”

Enjoyment is not a bad word when it comes to an art exhibition. With solid theoretical and historical foundations, Kinetismus offers a space for both learning and having fun.

This points to an aspect that is not so often a central consideration in an exhibition: the experience of the visitor. Through its selection of artworks and their placement in the different rooms of the Kunsthalle Praha, the exhibition becomes a cabinet of curiosities and a space of wonder and enjoyment. For some, this might be seen as a shortcoming (“the exhibition is not serious enough”, “the artworks do not have «space to breathe»”), but it is quite the contrary. By combining artworks from very different chronological moments and letting them “contaminate” each other with light and sound, the space that is created becomes less and cathedral and more a bazaar (in the sense of Eric S. Raymond’s influential essay from 2000), in which the visitor can choose what draws their attention and experience each artwork with a sense of surprise, letting the piece develop its process and reacting to it.

Enjoyment is not a bad word when it comes to an art exhibition. With solid theoretical and historical foundations, Kinetismus offers a space for both learning and having fun with a type of art that does not stare down from a high plinth but involves the viewer in its ever-changing process. Enjoyment brings with it a positive experience with the art, sparks interest, and leads to learning and appreciating the artworks in their context.

Art that moves, that stimulates thought and emotions, is remembered and valued. “Plugged-in art,” from kinetic to generative and AI-generated, has the ability to move, in every meaning of the word. It should always be presented in a way that allows it to do so.

References

Havranek, Christelle (2022). Introduction. In: Weibel, P. and Havranek, C. (eds.) Kinetismus. 100 Years of Electricity in Art. Prague and Berlin: Kunsthalle Praha, Hatje Cantz, 2022.

Shanken, Edward (2009). Art and Electronic Media. London: Phaidon Press.

Weibel, Peter (2022). 100 Years of Electricity in Art. In: Weibel, P. and Havranek, C. (eds.) Kinetismus. 100 Years of Electricity in Art. Prague and Berlin: Kunsthalle Praha, Hatje Cantz, 2022.