Pau Waelder

Erwin Driessens and Maria Verstappen have worked together since 1990 in the creation of process-based artworks using software, robotics, film, photography, sculpture, 3D scanning, and many other analog and digital techniques, as well as enabling, manipulating, simulating or documenting physical, chemical and biological processes, including plant growth. Following the presentation of their artcast The Kennemer Dunes, curated by DAM Projects for Niio, we have discussed the main concepts that drive their artistic research and the processes behind some of their most influential artworks.

Kennemerduinen 2010, scene E, 2011

Process is a key concept in your work, that is carried out automatically by programmed machines, spontaneously occurring in a natural environment, or happening through physical and chemical reactions. Why is creating, enabling or documenting processes so fundamental to your work?

Not all generative processes are equally interesting to us. We are mainly focusing on decentralized processes, the so called bottom-up processes. In these processes the patterns are not defined by a central authority but by local interactions between a vast amount of decentralized components. Examples for this are bird flocks, ant colonies, market economies, ecosystems or immune systems.When we study the landscape, what we see are the interactions of the elements in the ecosystem that react, adapt, and evolve over time. And that is also exactly what we try to model when we work with computers: the interactions of many small elements that together create a coherent global structure. We try to express that in the generative systems that we build. For us, this way of working implies another role of the artist. In the tradition of art, artists tend to work top-down, taking a piece of material and then shaping it to match an idea they had on their mind. We’d rather take a step back and see how the material can organize itself, albeit creating certain preconditions. As artists, we create a process that can make something by itself or react on the stages of development, so that it is the system that shapes the product instead of us determining how the material has to be formed. So there are different angles on why we are so interested in process, self organization, and evolution.

“As artists, we create a process that can make something by itself, so that it is the system that shapes the product instead of us determining how the material has to be formed.”

Time is also an important aspect in these processes, of course. A landscape has many timescales: there are things that take ages to form, while others belong to a shorter time scale, like the seasons and the flowering. So there is this relationship between the different timescales that make it hard to understand exactly what has happened and why it is exactly like that. But when we look at the landscape, we feel the natural intertwining of all those small and big events that have led to the big picture that we see in front of us. And I think that’s why landscape, as a genre, has such a long history in art, because these inimitable processes, which take place differently in every place on earth, constantly evoke new aesthetic experiences in us.

Kennemerduinen 2010, scene H, 2011

In relation to the factor of time in your work, in The Kennemer Dunes the process is sped up, but still shown at a slow pace. What do you find most interesting about this slowness?

In the Landscape Films (2001-2010), we create an acceleration by the compression of time. We decided to do this because we experience the landscape at a given moment in time and we cannot predict or remember exactly how it looks in another season. We chose to show the series of still images in the form of a slow, fluent movie of around 9 minutes to enhance our perception of the slow, but powerful seasonal transformations. What we did here, then, is to take a picture from the same place on the same time of the day during different days over the course of a year. This gave us the opportunity to notice small things one would usually not pay attention to, the subtle changes in the landscape that happen at a pace that is the pace of nature and not humans.

What we created is related to time-lapse animation techniques, but we decided not to simply put all images one after another, because that would generate a very hectic activity, with clouds passing by quickly and plants nervously growing towards the sunlight. In our view this would not support the landscape experience, so instead we chose very few images, around 52, and added a 10-second transition between them. The transition between each photo is not a proper representation of what has happened there and then, because it is just interweaving the pixels of one picture to the other. So it is not accurate as a document, but as an experience it is more accurate, because it keeps the quietness of the experience of contemplating the landscape.

A third outstanding aspect of your work is that of categorization and collection, as is made evident in the Morphoteque series or in Herbarium Vivum. What can you tell me about these artworks?

In these works, where we deal with static forms, particularly in the Morphotèque series, we always have a collection of objects that are expressions from a certain process and then we want to show the variety of the different outcomes. For instance, the Vegetables Collections (1994-2011) consist of rejected vegetables that have been collected by us from groceries and markets, and then cast as a sculpture, in order to preserve them, as they will obviously decay. We could have taken a photograph, but since the work is about morphology, we needed to keep the three-dimensional form rather than just an image. This work comments on the fact that, in our industrial world, we want our food to be produced in perfect and identical shapes. This is convenient for the machines that harvest and process them, but it is also the result of an aesthetic decision. But of course the plant growing the vegetable does not follow these principles, so it can produce asymmetrical or “abnormal” vegetables, which taste the same as the “perfect”-looking ones, but nevertheless are put apart and used for cattle fodder or just thrown away.

By collecting and preserving these irregular specimens, we show the wide variety of possible growths within a particular plant species. And that they are visually more rich-than the symmetrical and straight forms that we normally get to see in the supermarket. This type of work also gives us an opportunity to talk about processes that you cannot carry out in any museum space or in an art space. You cannot show the growth of a pepper, but each selected shape refers to an individual growth process, while the collection as a whole also shows the typical similarities.

What drives you to create physical objects out of algorithmic processes (as in Accretor) and real space mappings (as in Solid Spaces)? What does the physicality of sculpture bring to your work?

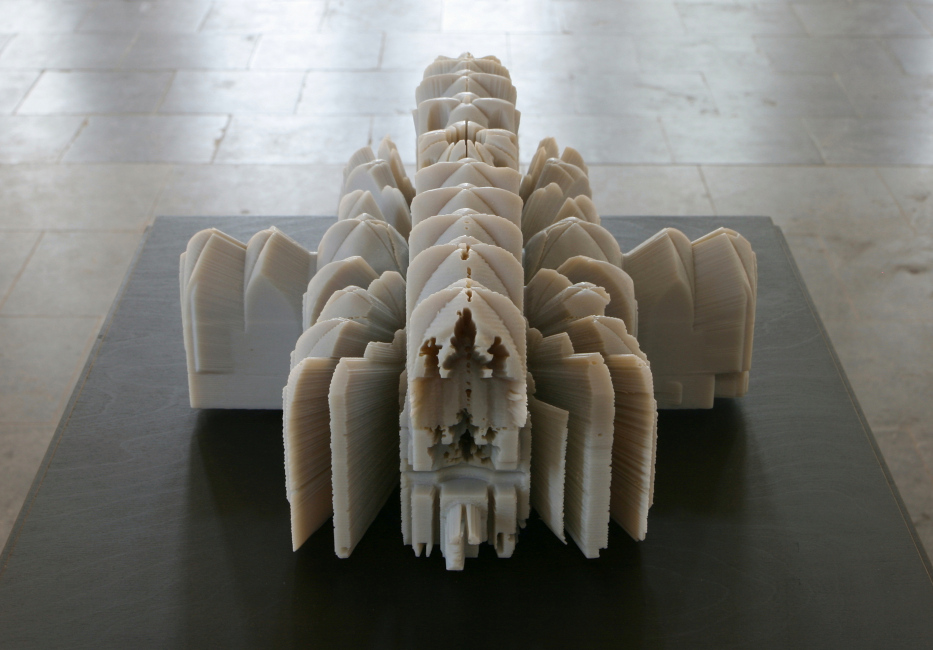

In Solid Spaces (2013), particularly, there was an interesting connection between the process, the space, and the outcome. We had the 3D scanner working inside the church, we displayed two sculptures that were made from previous scans of the interior of the church, and there was of course the architectural space of the church itself. People could see all of this at once and relate the objects with the space and the process of production. One thing we like about 3D printed objects is that we can create them by letting the machine look at something in the real world, an existing church for instance, but it can also be a completely virtual object, existing in a digital space. In the latter, the object that has been generated using generative software can be so complex and detailed that it might be difficult for the 3D printer to produce it.

The Kennemer Dunes can be connected with your diorama artworks of that time, Sandbox and Hot Pool, which also show a slowly evolving landscape, although through different means. Which connections would you make between these different types of landscapes?

All these works relate to our fascination with decentralized processes. What we did in Sandbox (2009) and Hot Pool (2010) is that we reduced all the elements that are in the landscape to three things: the box itself, which hosts the diorama, the wind or heat, and the particles of sand or wax. In Sandbox we create artificial winds using 55 individual fans placed on the roof of the box, with a software program that controls them. However, the result is not a pre-planned choreography, but there is an unpredictable process involved that turns on and off the fans. Of course, the wind shapes the dunes, but in turn the dunes change the direction of the wind.here is a complex interaction between the sand and the wind that is less deterministic than one might imagine. The geometry of the box causes even more complex turbulences, so in making these seemingly simple miniature landscapes, we realized that they are not so easy to understand and predict. If you change one little thing, it has an influence on everything, even in this very small secluded world. This is also something that we discovered working with software: when you change one of the many parameters a little bit, it can have a really dramatic effect on the whole. And that’s exactly something that we would like to communicate with our work: when you change a little thing in a complex system, when you take out one species, for example, one plant, or you change the temperature just one degree, everything changes and often in an unpredictable way.

“We, as human beings, have to be more in balance with the ecosystem that we are in, and we should be humble when we interfere in systems that have evolved over many years”

Most things in the world are part of a complex system. So we, as human beings, have to be more in balance with the ecosystem that we are intertwined in. And we should be humble when we want to interfere in existing systems that are in balance, or have evolved over many, many, many, many years. We think we understand the system and that we can control what will happen when we change it. But actually, we always create a reduced model of the system and we let out some small things that we think are not important. And then it turns out that it’s this very small thing that you did overlook that is very influential in the end.

E-volver, 2006. 4 breeding units with displays, 5 prints on canvas 600 x 300 cm. Permanent installation, interactive software. Research Labs, Medical Center Leiden University. Commissioned by LUMC Leiden and SKOR Amsterdam.

Works like E-volver and Breed deal with artificial evolution programs. How would you compare the processes involved in these computer simulations with your work with natural processes, either observed (Landscape Films, Pareidolia) or manipulated (Tschumi Tulips, Herbarium Vivum)?

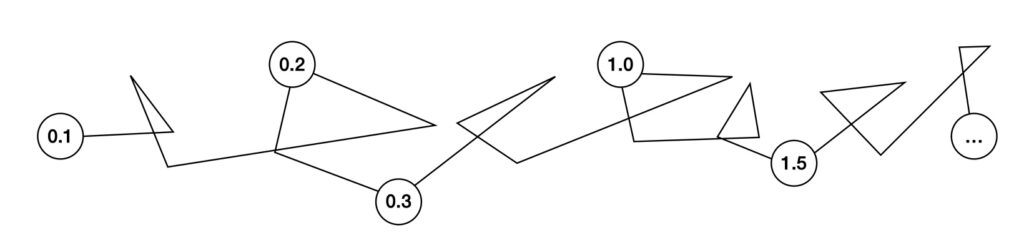

We are interested in evolutionary processes as a kind of bottom up, decentralized process. Evolution is difficult to observe in the real world because adaptation to the environment and the passing of information to the next generation is rather indirect and it occurs in small steps. But if you manage to model this slow and gradual process in the computer, it suddenly becomes observable, largely due to the acceleration of time (like in the landscape films). So in recent years we have set up a number of projects in which we have used evolution as a step-by-step development of an artwork, but also as a way of not completely controlling the results (due to the complex feedback loops involved).In Breed (1995-2007), for instance, the process of mutation and selection is completely automatized, there is no human intervention. The artificial evolution takes place completely in itself, because the fitness score is determined by objective and measurable properties of the shape: the form that is generated inside this virtual environment should be structurally correct and be able to be materialized as a real object. In E-volver (2006), there is human intervention involved, since the mutations and variations of the animations are influenced by the subjective preferences of the people that interact with the work E-volver was made for the Research Labs of the LUMC in Leiden, where scientists and students in human genetics can grow abstract, colorful animations on four breeding units via a touch screen. It’s there now for I think 16 years, and it’s still working. It is always creating something new, and people can see that they have an influence on the outcome of the program, but it is more of a reactive intervention than a creative one. E-volver involves an unusual collaboration between man and machine, providing a breeding machine on the one hand and a human “gardener” on the other. The combination of human and machine properties leads to results that neither could have created alone.

The outcomes of these artificial evolution programs can be connected with the Vegetable Collections in the sense that they also show how the industry speeds up evolution towards the genetic code that produces a set of desired outcomes, such as round potatoes and straight carrots, while what we want is to show the diversity in these morphological processes. We are equally interested in showing both the results of this virtual growth process in terms of diversity and detail, and the industrial production process that is automated from design to execution. Our approach shows that technological manufacturing processes do not necessarily have to lead to standardization, control, simplism and homogeneity, but to the contrary. When we started these projects in the 1990s, people were not used to computers as an artistic medium, and we had to explain that the artworks were generated in the digital realm, with digital processes, but now people understand that this is something that is created artificially.

Pareidolia, 2019. Robotics, microscope, camera, perspex, wood, metal, sea sand, screen 50 inch, black coated metal housing. Commissioned by SEA Science Encounters Art.

In your recent works, Pareidolia and Spotter, the task of observing nature is carried out by a machine through cameras, face detection software and machine learning models. It seems that this leads to a fully automated and autopoietic system, is that what you are looking for? Which possibilities do you see in machine learning for your future artistic projects?

We started working with neural networks some 10 or 15 years ago, but back then the computer processing speed was so slow that you could only do something very simple, and then it would take days before you could see the output. So it was very limited, but later on, when it became more achievable, we dived into it. However, we are reluctant to further elaborate on it, because artificial neural networks tend to take on an aesthetic that comes from the system itself and therefore all the artworks generated by these techniques look more or less similar. And it’s also very hard to understand how it works, beyond the fact that you can influence the training of the machine learning program by selecting input images and also some other training parameters. But what it has brought us so far is not very satisfying. Certainly now, with programs such as DALL-E or Midjourney, there are interesting possibilities to explore. These are very complex systems based on enormous amounts of data, and it can only be run by big companies and universities. Everyone can actually rent the software as an online service. As artists we are interested in building the systems we work with, not just using them to obtain specific results. So for us there is little to gain with these text-to-image generation systems.

“We do not want to work with a big black box and wait for something to come out of it, without understanding anything about it. We want to build the system we are working with.”

The relation between process and result must also take place on the level of creating the system. We do not want to work with a big black box and wait for something to come out of it, without understanding anything about it. Although the systems that we build also are hard to fathom, in the end, we do have a very satisfying understanding. It’s a deeper understanding of what you cannot control. For instance, in Pareidolia (2021) we created a robot that uses machine vision and face detection to identify human faces in the texture of grains of sand. We built the face recognition program ourselves so that it would work on sand particles rather than the usual application of such software. Although it is hard to understand how the artificial brain learns to distinguish a face from something that is not a face, it was very satisfying to build the software based on our own database with tens of thousands of images. And then to see it applied to sand, whose morphology is really rich but too small for us humans to perceive. If you think that every sand particle in the world has a unique shape, then you can imagine a gigantic amount of sculptures that are right there under our feet. Applying machine learning to our own face detection software has so far been more interesting and satisfying than the potential of generative neural networks (GANs), yet another type of machine learning. But you never know, sometimes it can take quite some time before you are able to transform and internalize the possibilities opened by a new technology and use it in a personal and original way.