Pau Waelder

Chinese-Australian artist Thomas C. Chung has embarked on a lifelong artistic research that he is developing in well-structured phases, each one characterized by an exploration of different techniques and approaches to human experience. He earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of New South Wales’ College of Fine Arts in 2004 and has had a noteworthy international artistic presence in recent years. Chung has been a representative for Australia in several prominent international exhibitions, such as the 2nd Land Art Biennial in Mongolia, the 4th Ghetto Biennale in Haiti, and the 9th Shiryaevo Biennale in Russia. Currently, he is exploring the realms of psychotherapy as a means to deepen his artistic inquiry.

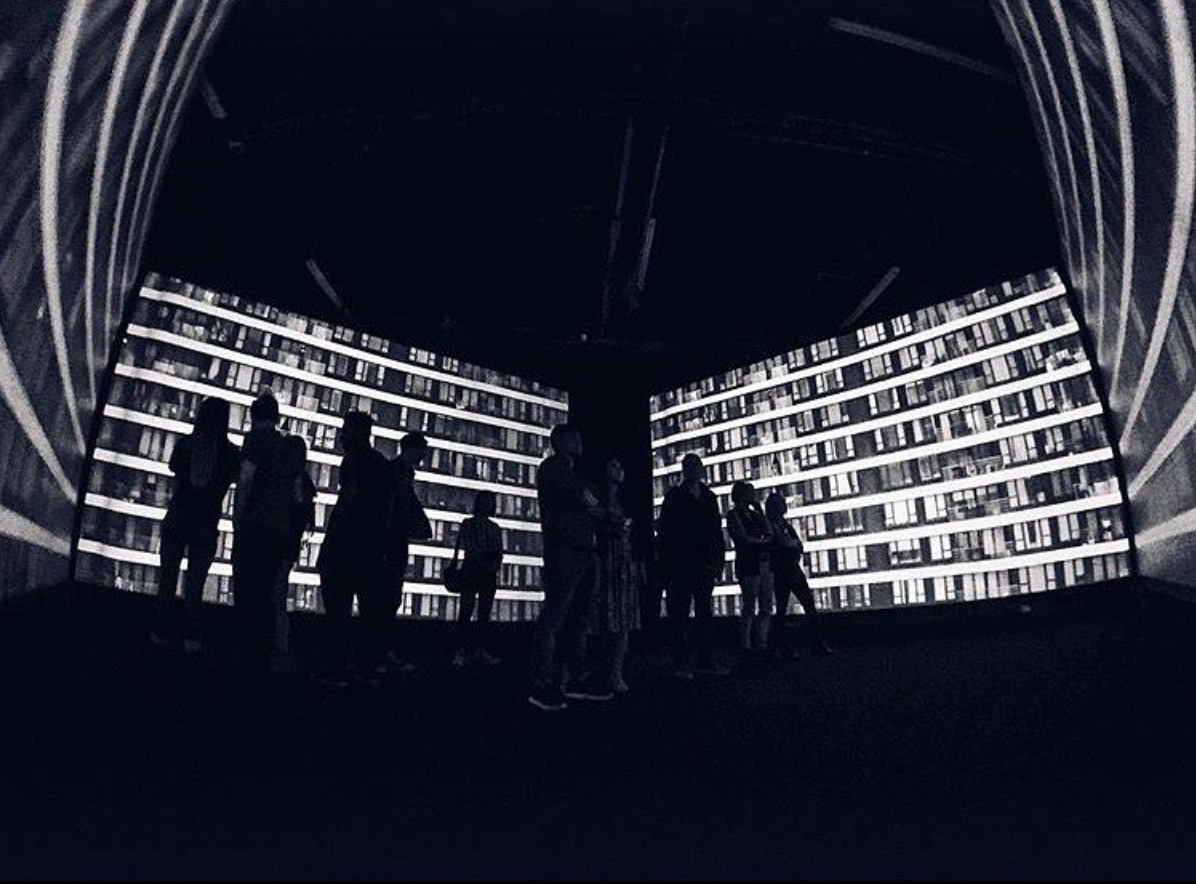

The artist presents on Niio three pivotal works from his ongoing second phase, in which he leaves behind a narrative focused on childhood innocence and enters the adult world with a series of more sober, meditative artworks. The landscapes that form the collection “As Far As I Could See…” introduce a deeper reflection on the human condition, not without a hint to the magic and surreal aspects of children’s imagination.

Experience Thomas C. Chung’s dreamlike landscapes

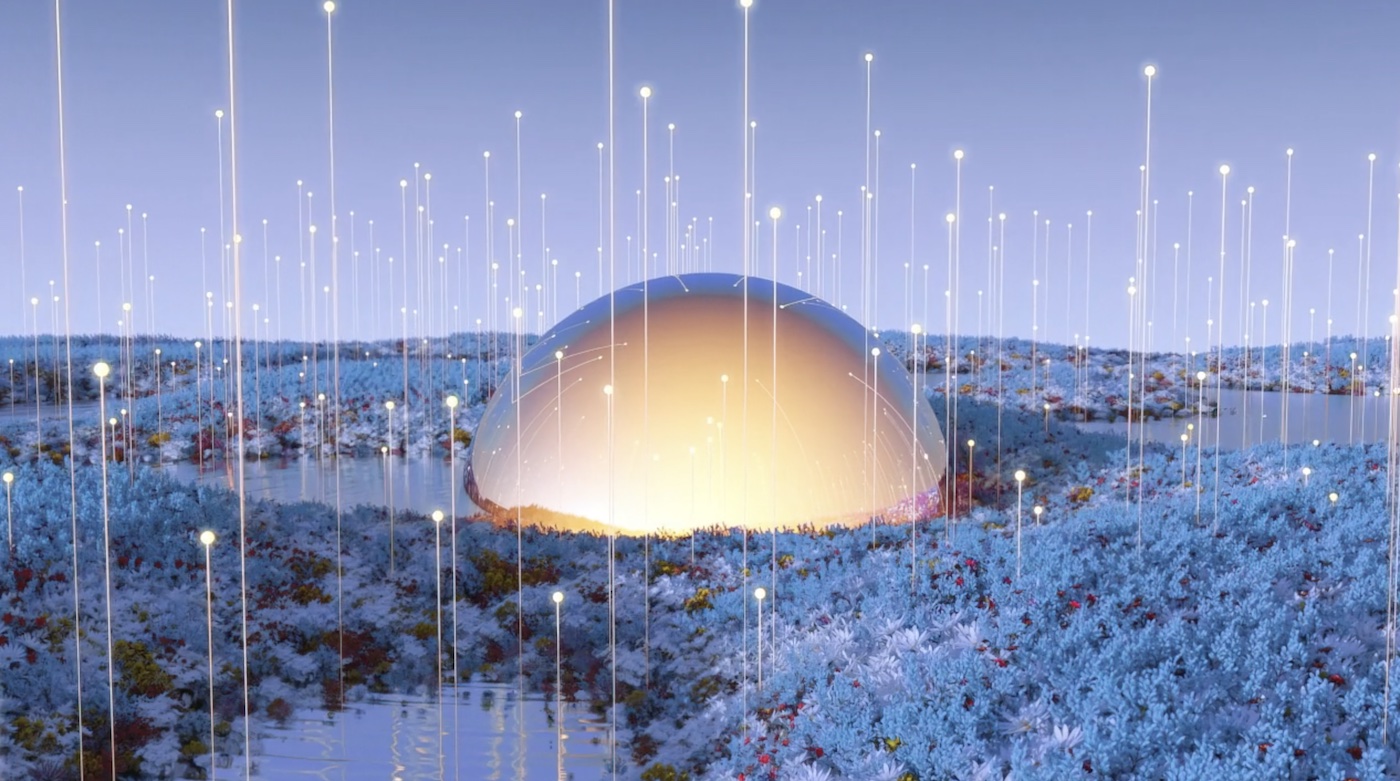

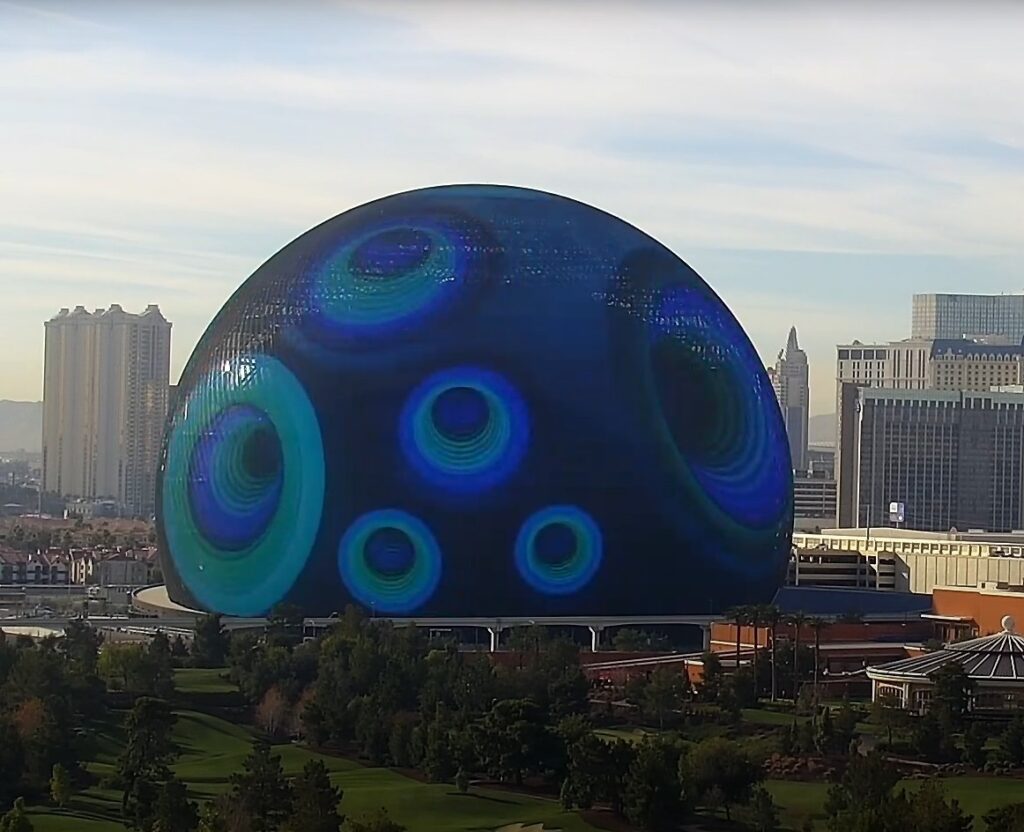

Thomas C. Chung. “As Far As I Could See…” (I), 2023

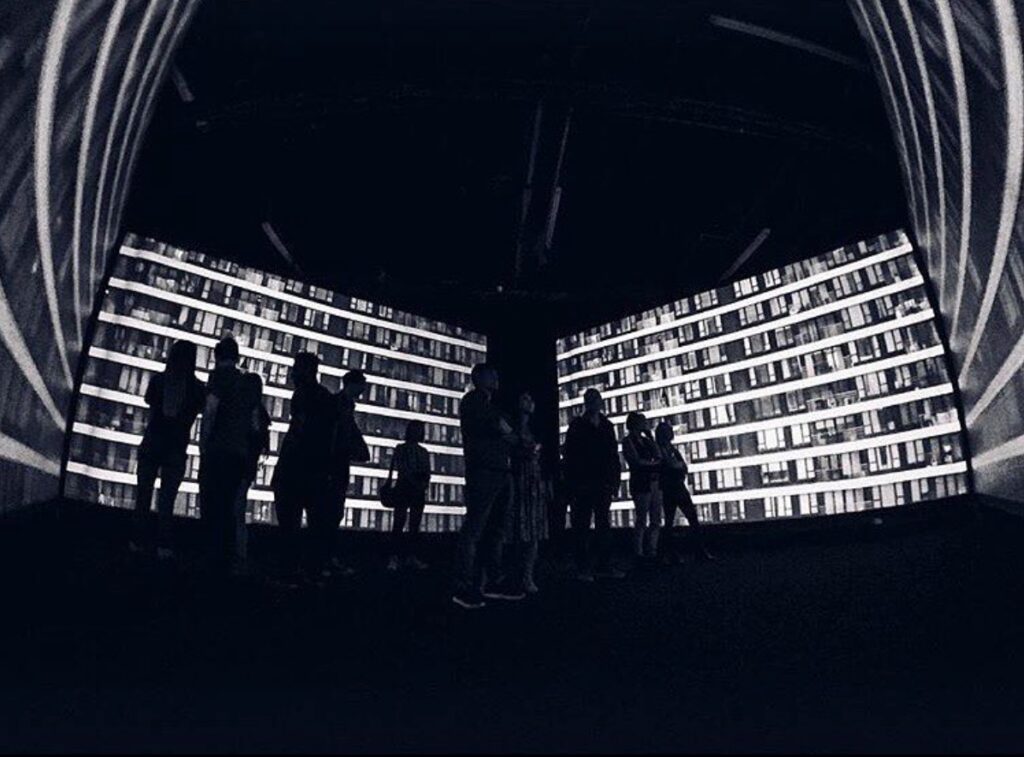

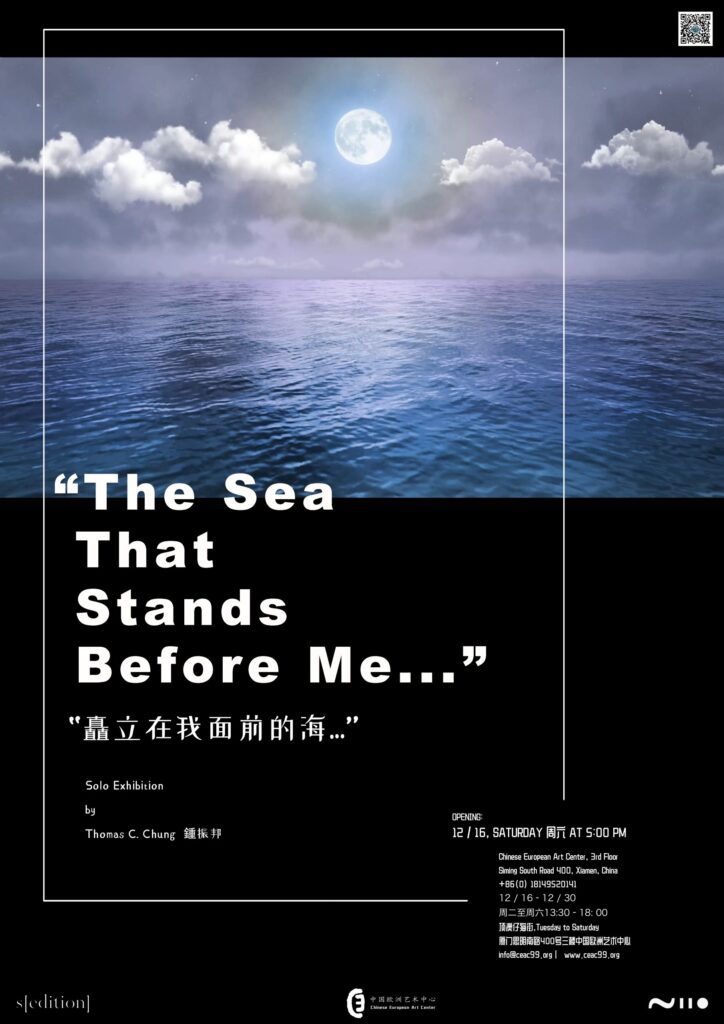

In the following interview for Niio, Chung discusses the motivations behind his work and dives into his second-phase artworks, which have recently been exhibited at the Chinese European Art Center (Xiamen, China) in a solo show titled “The Sea That Stands Before Me…”

Your work has evolved over the last decades following a “lifelong narrative” determined by different phases. The first phase was characterized by crochet sculptures, installations, and an overall playful aesthetic, while the second-phase works present a very different approach. It may even be hard to recognize the work of the same artist in these two phases. How have you dealt with this transition, and what has been the response to it?

I’ll be the first to say I was nervous about the different phases I had conceived – I figured it might be too hard for others to accept, especially with the small but loyal following I had built. Over time, I understood that as long as the work was fascinating to myself & others, it didn’t matter what shape or form it took as long as the creativity was there. I clarified this by using new techniques each decade, approaching the chapters within my Art by splitting them into various methods that correlated with the story I wanted to tell. The 1st phase was all handmade, tactile, labor-intensive & filled with food motifs as avenues for expressing a child’s obsessions & dreams. This 2nd phase speaks of the departure from childhood & the realization that life has to progress beyond our comfort zones so that we can understand the totality of our world.

I had a lot of interests as a child & wanted to grow up to be so many things, one of which was as a children’s illustrator & author. But Art chose me instead, so here I am, creating a different type of story, saving that option for later.

You have expressed that, in your work, you aim to see the world through the eyes of a child. How do you convey this idea without being perceived as childlike or superficial? Which is the underlying concept that grounds these artworks?

It aligns with how I interact with people these days in a direct yet open & gentle manner without overthinking the consequences. If others don’t appreciate it, I try not to let it matter. Everyone has their view or way of life. My artwork may have previously been seen as naive, which at times bothered me. I knew as a conceptual artist, my practice would be a lifetime’s work that would encompass the narratives of my inner child. The artwork titles are a hint to what it is they see & are presented to the audience as an observation of their journeys while exploring the world. To produce this lifelong story, it was always my vision to create a giant storybook-like body of work split into chapters, set within a contemporary art context, emphasizing the importance of patience, empathy & curiosity, where human beings have the ability to control what it is they feel or see.

Your video artworks are characterized by a slow tempo that suggests a relaxed observation. In our times of limited attention span and an overflow of media content, would you say that we need to take more time to observe our surroundings? In your opinion, does art create this space for observation or is it also caught in the spirit of fast-paced consumption?

That’s quite a complex one to answer. And that is a great question. I value the time I take to see the world unfiltered from electronic devices & media. Much of that is due to my not being attached to technology as early as others may have been. For example, the very first mobile phone I got was when I was 34 years old; I remember even thinking what a selfie of myself looks like.

Until then, I spent a significant portion of my life turning up early to meet friends or acquaintances (if they were over an hour late, I would leave), keeping promises that I had kept & looking at the sky to tell the time.

Art has always been a good reflection of our times, like a visual newspaper that begins & starts intriguing conversations before leaving it to others to visit, fulfill, react, or enjoy. The fast-paced consumption of our current world is an accurate indication of that, with the growth of digital art increasing among the masses.

Thomas C. Chung. “As Far As I Could See…” (II), 2023

You are studying to become a psychotherapist and draw inspiration from this knowledge to create your artworks. Do you intend your artworks to visualize or reflect upon states of mind, or do you wish them to become therapeutic objects, sparking certain emotions or thoughts that might have a healing quality?

This one made me think – thank you for that. My intention as an artist is to engage with everyone, but whether or not it connects with others is something I can’t control. Delving into the mental health field as a future psychotherapist, the purpose of whatever I create – however the audience receives it – there’s no right or wrong answer, just an open story. Food & landscapes have always intrigued me in this particular way. Some people love certain aspects or locations, while others dread it. Some people love a specific type of food but not others. No one person has the same reaction to different things & that’s what is so fascinating to me, to see life through the eyes of another human being.

When I create, I have a particular concept & narrative for it, but ultimately, if the audience would like to enjoy it without any background or story, that is also up to them. Viewing Art, like watching any movie, reading a book, or tasting a special menu, is very subjective.

“I’ve purposefully given artworks a title that invites an audience in…much like an open door to a gathering or party.”

You have mentioned your role as storyteller. How do you guide the narrative, from the title of the artwork to its description and the story that unfolds in it?

I’ve purposefully given artworks – particularly new bodies of work – a title that invites an audience in…much like an open door to a gathering or party. I grew up in an environment where Art was rarely seen as a necessity, so I knew the task for an artist was to be as engaging as possible – if not with their personality, then at the least with their artworks. Often, the title reveals a lot to the viewer & this should always be considered.

Once the artwork has been created & the title carefully selected (I have a list of names for potential artworks), it unfolds as an individual experience. Once invited, I leave the guests to wander around to enjoy the ambiance of it.

Thomas C. Chung. “As Far As I Could See…” (III), 2023

You are exploring “emotional landscapes.” Coincidentally, this is a term used by the singer Björk in her song Jóga, in which she refers to being puzzled by emotions and undergoing a healing process. Is this how you understand your exploration? Or is it more of a distanced observation?

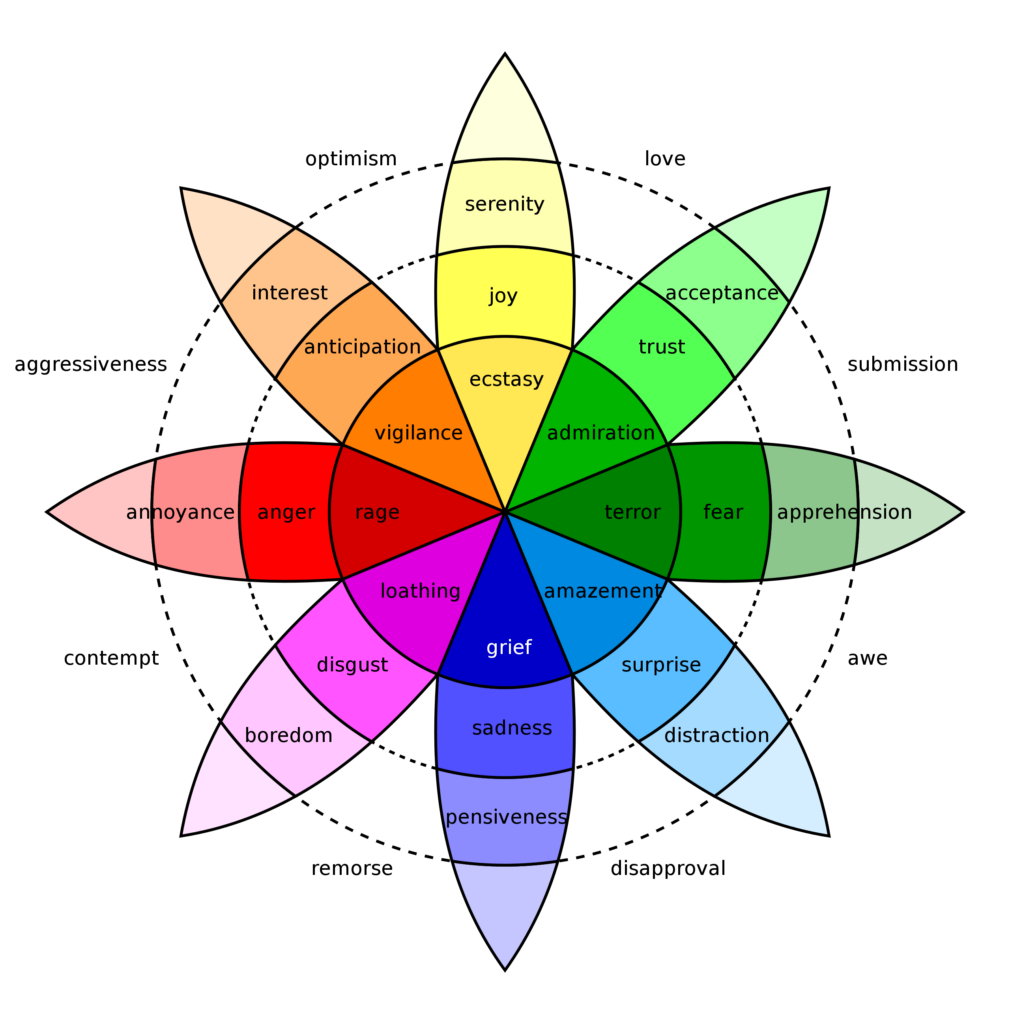

Oh – how wonderful. Thank you for this observation. I’ve been a big fan of Björk for many years, especially when I was younger…yet I never put the terms together like you did. I love this connection. I know the words ’emotional landscapes’ popped into my artistic practice at a time when I noticed how viewing one place or space brought out differing reactions & sensations in others. A lot of this stems from my studying in psychotherapy, where no one situation is identical, although similar when answered by participants or clients. For some, this exploration could be seen as somewhat distanced yet intimate. The space in front of us isn’t necessarily a gauge for how close one feels towards something.

“These artworks point to a departure from childhood innocence, but also to longing for the past in a way that color cannot achieve.”

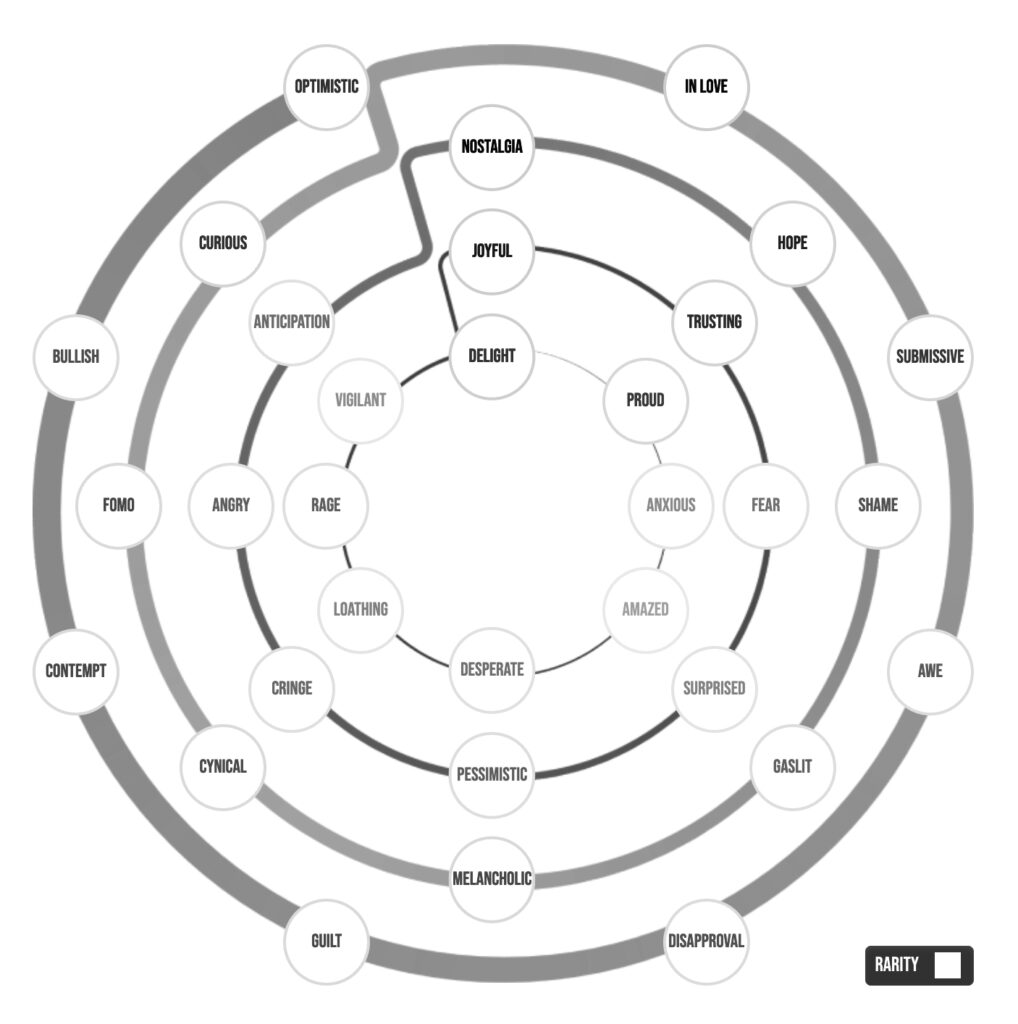

The series of artworks you present on Niio address the ability to find hope during times of hardship, which is something that everyone can relate to. The aesthetics and elements in them point to a more sombre, even melancholic atmosphere. Would you say that these artworks represent a coming of age, leaving aside the innocence of childhood and confronting the hard truths of adult life?

This series with Niio is particular in its aesthetics & I chose a black-and-white palette to illustrate this story. I’ve always found the limiting of colors to be very intriguing. I love to watch vintage movies because they have a very special quality. Sometimes, it can feel melancholic, while at other times, it can feel deeply romantic. These artworks pointed to a departure from childhood innocence, that’s for sure, but it also alludes to the longing for the past in a way that color cannot achieve. I wanted to insert an intangible without stating something obvious so people could have their journey & time to think for themselves.