Pau Waelder

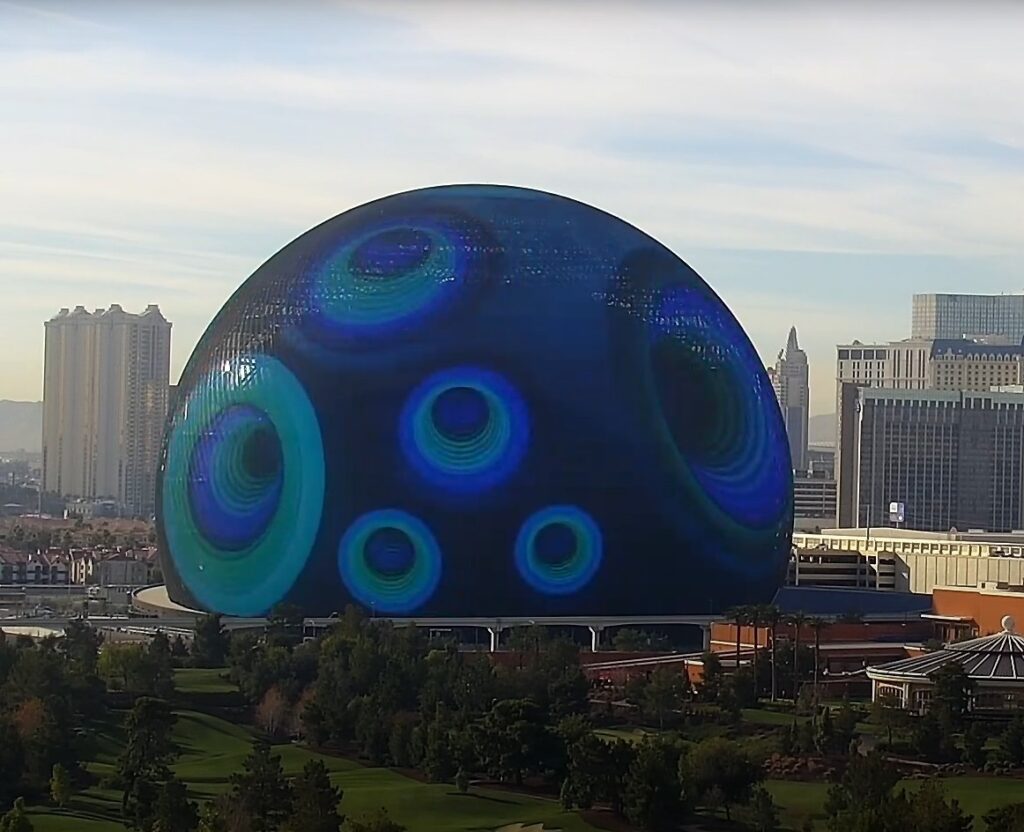

3D motion designer and visual artist Kian Khiaban has had an outstanding trajectory since he graduated from UCLA in 2015. Working early on with fellow artist Refik Anadol, he has closely collaborated with him in some of his studio’s most spectacular projects and is now part of the team at the world famous Sphere, a groundbreaking spherical screen with 580,000 sq feet of LEDs. Khiaban’s artistic work focuses on nature and abstraction, conceiving art as a way of addressing human emotions and engaging in healing processes.

The artist has recently presented a solo artcast featuring five artworks in which he creates fantastical landscapes that depict different emotions. In the following interview, he dives into what these imaginary spaces mean to him, as well as his creative process and his views on the current state of digital art.

Dive into Kian Khiaban’s Emotional Landscapes

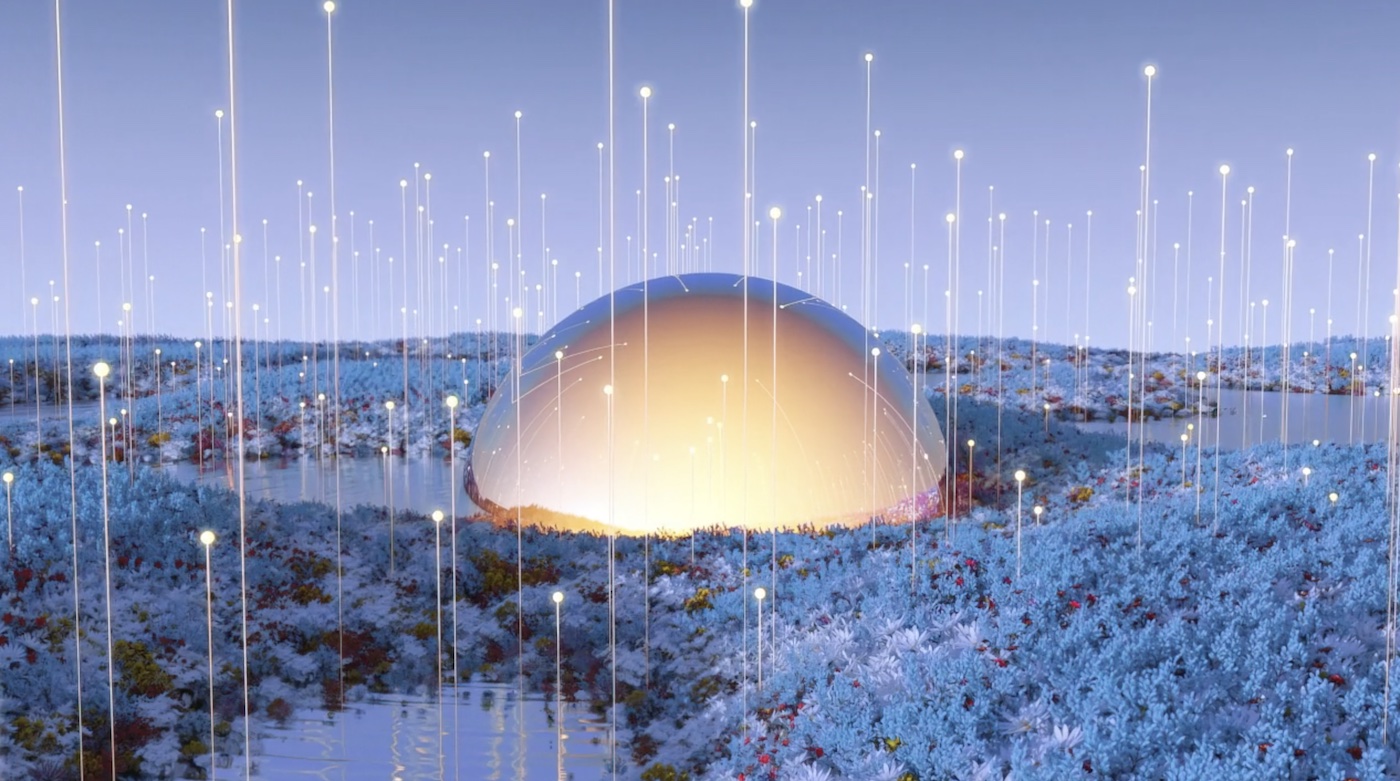

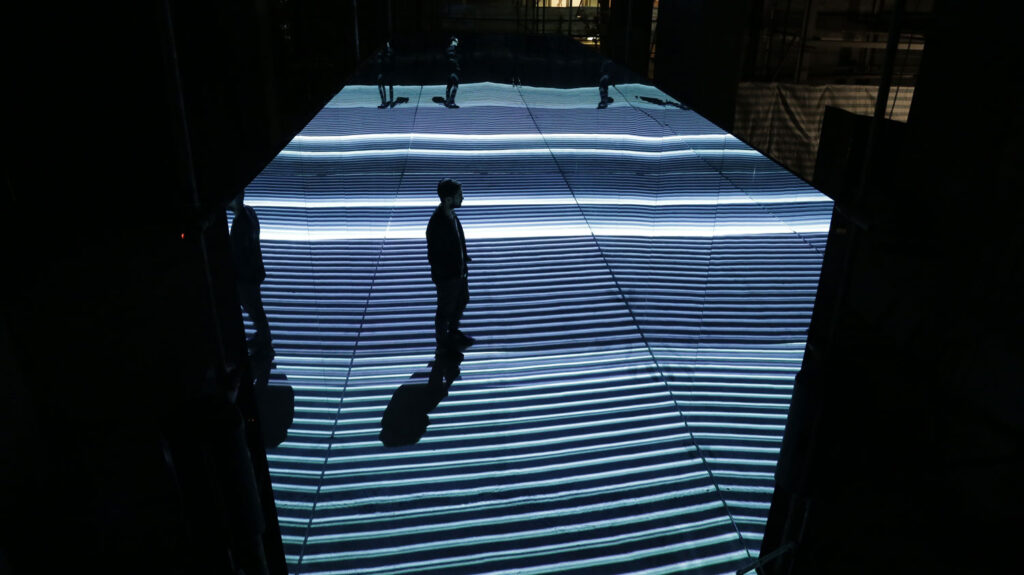

Kian Khiaban. Floater, 2021.

How did you get started in 3D animation? What interested you about this particular aspect of digital creativity?

I started doing 3D when I was thirteen. I got introduced to it through anime forums, actually. In the anime forums, every user would have their own design, which they called a signature, and they would teach people how to make their own signature. So through this I got introduced to Photoshop and 3D, and then when I went to university, I already had a whole portfolio of still images. They weren’t animations, they were just art. There I started to learn how to move the things that I had made. At UCLA I met Refik [Anadol], who was a grad student. He was using Cinema 4D, a professional 3D modeling, animation, simulation and rendering software. It was a good match between us, because we were both heavy C4D users, and then at some point Refik had an exhibition and I offered to help him, so we started collaborating and I worked my way up into his company and was part of its early establishment. This was around 2015, when I graduated.

“The way we worked [with Refik Anadol] is that he gave me a lot of freedom, maybe throwing an initial idea, and then I would go crazy with it.”

You have created numerous animations for the studio of Refik Anadol. Can you tell us about your creative process within this context? What have you contributed and what have you learned from this collaborative practice?

Working with Refik mainly consists in that he would come to me with an idea, especially a visual idea and would say: “this would be really great if you can make something like this.” I was very good at iterating, so I considered myself, especially at that time, a remixer. I created a lot of the visuals of the projects we were doing at his studio. For instance, we had a project called Infinity Room. Refik said he had the idea of a room with mirrors on the top and bottom. So I experimented a lot, I did the sound design for it, made some animations, and gave it a particular character. Then Refik added some visuals onto it. In some projects he would take the lead, while in others I did for particular things. But the main characteristic of the way we worked is that he gave me a lot of freedom, maybe throwing an initial idea of what he was looking for, and then I would go crazy with it. Sometimes the project would develop in a totally different direction, but always with this ongoing conversation between us.

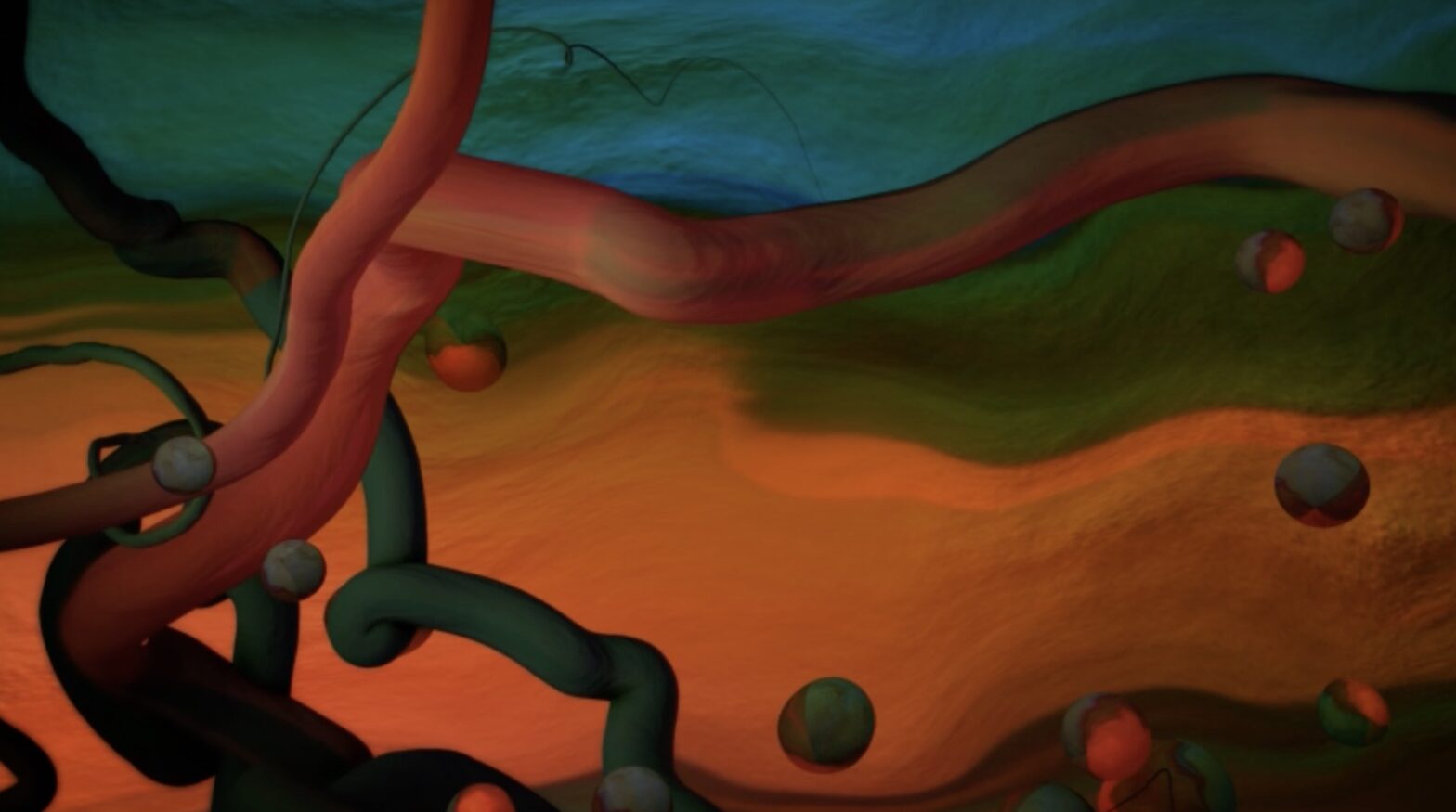

Kian Khiaban. An Open Heart, 2021.

On the other hand, I have also learned a lot from my commercial work, where I am given a style frame and I work on that, building an entire animation, and remixing it. I’ve gained a lot of technical knowledge and benefited from working with a team, which is something I love because it brings me multiple perspectives that widen mine. I would say that I’ve been lucky because in these jobs the clients have trusted me and given me a lot of freedom, and even allowed me to have some of my personal themes in my work. What I learn in my commercial work I later on apply it to my personal work. Working on one of these projects for eight hours every day, you get to experiment so much, and so I often develop things that seem perfect for one of my pieces, and then of course my personal work also inspires what I do for different clients.

“I love working with a team because it brings me multiple perspectives that widen mine.”

Currently I work at the Sphere in Las Vegas, in R&D and building the animations, and this is a very challenging type of shape because it is seamless. And you know, 3d animators don’t design in a seamless way. In addition, the form has to be a spherical camera, so there are a lot of little things you have to adjust for. But to be honest, I’m good at coming up with a lot of ideas, and then making things a bit prettier with each iteration. That’s what I do.

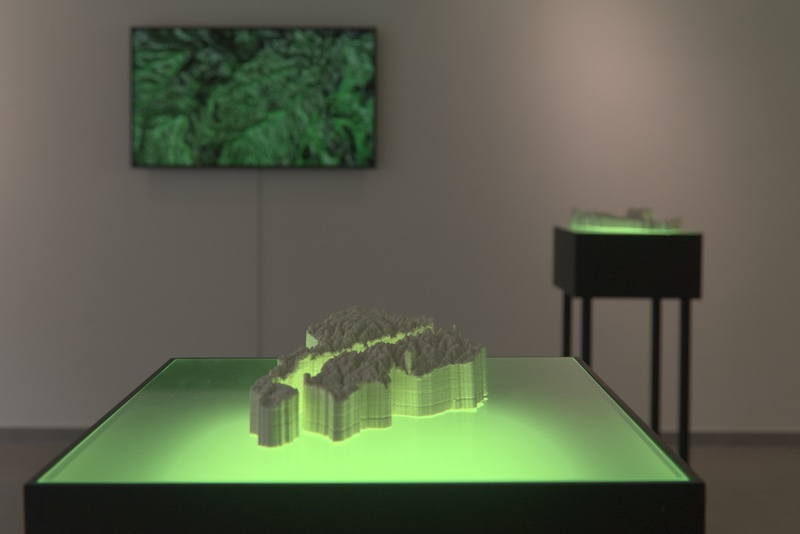

The animations you have created have been displayed in very large installations and on the facades of famous buildings. How do you work on them when considering such a large scale, and an interaction with architecture?

The process starts by making a 3D model or a miniature of the building, because you need to be able to feel what you’re doing. If we don’t have the possibility of building a miniature version of what we’re doing, we do a VR version, building the space in 3D and then applying the projection. That gives you a starting place to experiment. But besides that I like to first consider where the building is located, in what city, what kind of environment is there around the building, what form does the building represent, and so forth. Then I try to build on top of that, but it depends on the project.

For instance, in WDCH Dreams, at the Walt Disney Concert Hall in LA, there was the almost impossible task of mapping the shapes of Frank Gehry’s building, for which they had had developers working for years. We used 42 large scale projectors that were able to display 50K resolution images. We used the entire facade as a screen, applying the visuals I created to a 3D model in order to adapt to the undulating shapes.

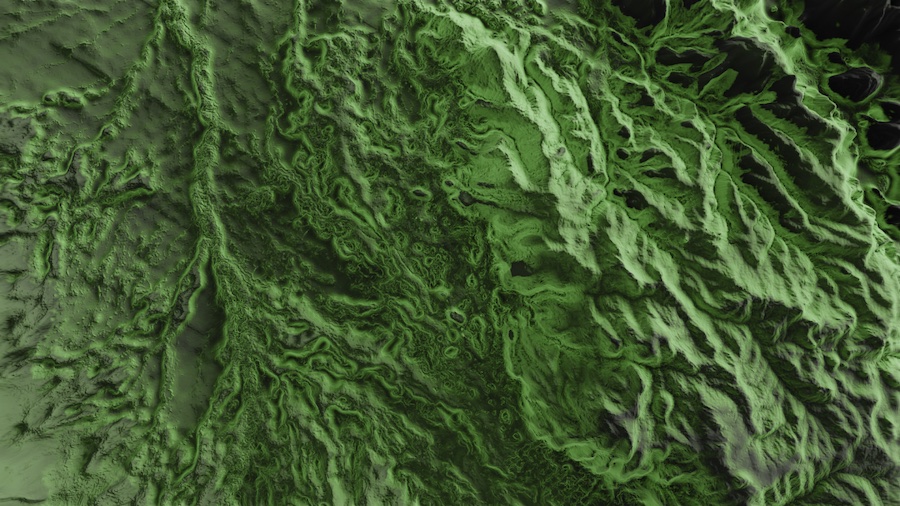

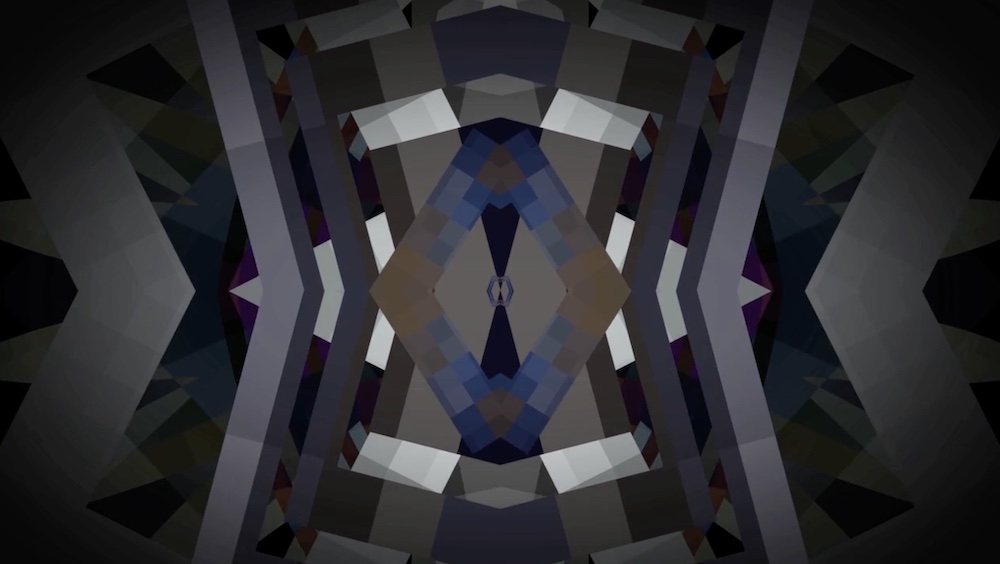

Kian Khiaban. Long Walk, 2023.

Your personal work is often characterized by an interest in nature (real or imagined) and mesmerizing visual effects in which light has a critical role. What attracted you to creating these fantastic worlds and the lively activity that takes place in them?

I’ve always liked hiking a lot. When I was a kid, there was this one place I went to that brought a lot of peace in my mind. When you go into a natural setting by yourself, it becomes a way of finding yourself because you’re getting this new clarity and simplification. You can actually hear your own thoughts, and to me that is very relaxing. So I like nature because it has that healing quality of bringing clarity, lowering the volume and allowing a space for reflection.

As for the dream-like quality of my work, I believe it is related to who I am. I was a big daydreamer as a kid. I would play out scenarios a lot in my head, and I also spent many hours, year after year, in front of the computer. Playing video games and searching the Internet took me to a distant place, away from daily reality, and I think what I do now is a more sophisticated version of that. I’m building this space for myself to bring me peace and clarity, the same way when there was chaos around me, I could go to a video game and be taken into that fictional world.

“I like nature because it has that healing quality of bringing clarity, lowering the volume and allowing a space for reflection.”

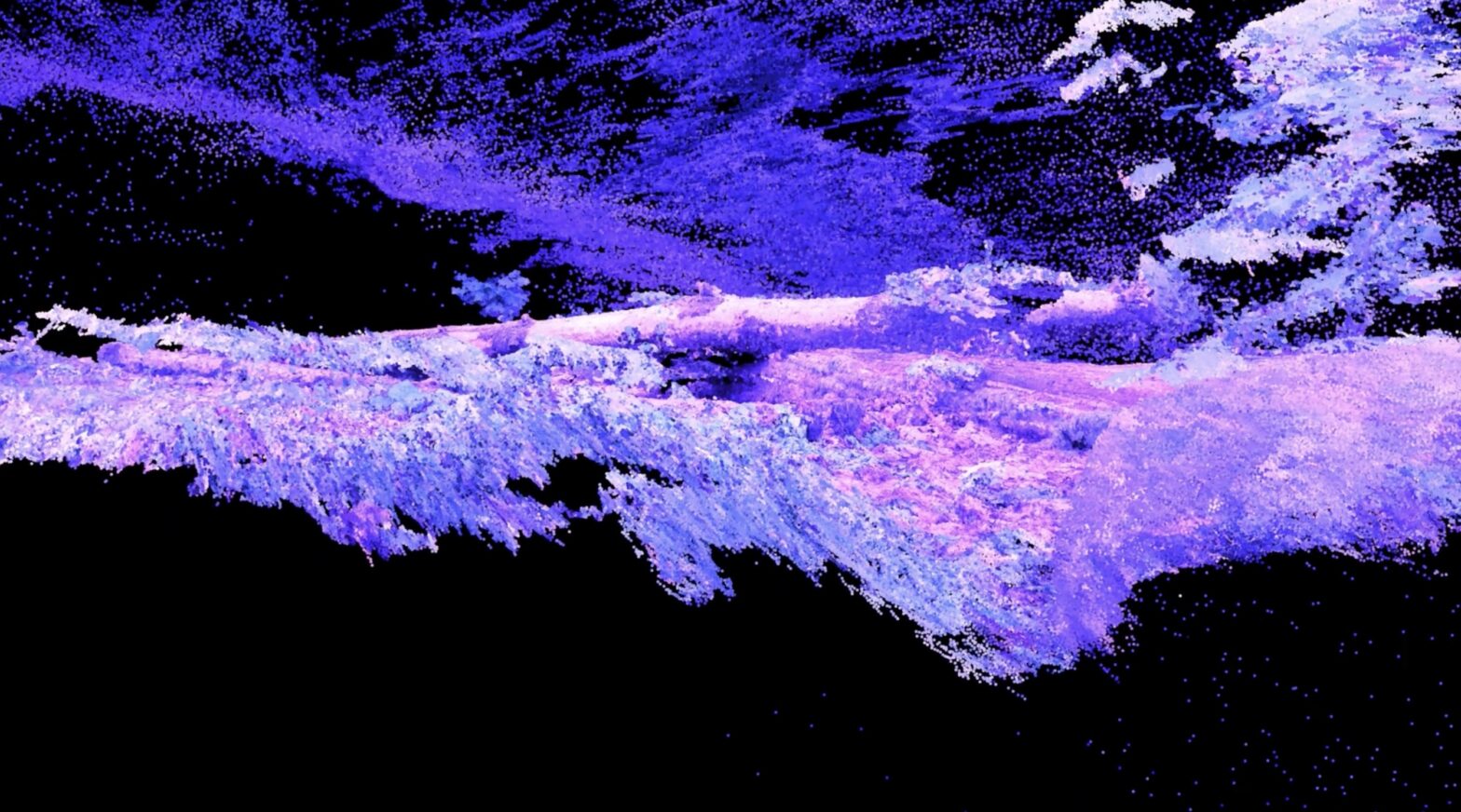

In the artworks we now present on Niio, a common denominator is the depiction of emotions through digital landscapes. What do you find interesting about representing emotions in this way?

Maybe I should talk about why I always have a light in the center of each artwork. I don’t want to impose my intentions on the viewer’s interpretation of the artwork, but I think it is worth explaining this. The light represents the hope of getting out of a hard situation, the objective you try to follow to achieve that, and that makes you very focused. I feel that what has helped me survive in my chaotic environment all these years is being really focused. The light obviously has other meanings, it can be the sun, that so many civilizations have praised as a God, or the light that people having near death experience say they have seen in a pleasant field, and that has brought them the most peaceful feeling they’ve ever felt in their life. So what I mean is that these artworks are for me a way to express something personal, even intimate, in a more abstract form. For instance, one of my latest pieces is called Adrift at Sea, and it refers to the feeling of having to choose among different values and not being sure what to pick, which made me feel a bit lost.

Kian Khiaban. Wisdom, 2020.

Despite this personal connection with a human experience, there is generally a lack of human figures in these landscapes, why is that?

I want it to feel lonely. It’s that feeling I get when I go into nature, there’s no one around me. But it is not about loneliness: I can think of having people there, but it would change the whole dynamic of the piece. It can become about them, and I am not interested in representing people in these landscapes, which would take you into figuring out what they are doing, but rather to express a feeling that you can only experience looking at this landscape where there is no one else but you.

“These artworks are for me a way to express something personal, even intimate, in a more abstract form.”

From your perspective as an artist involved in acclaimed large scale projects, what is your opinion about the current perception of digital art? Do you think it has finally become a widely accepted form of contemporary art?

Generally speaking, it is much more respected than before, partly because of the NFT boom. However, NFTs also brought negative associations, with purely financial speculation and lack of quality. On the other hand, 3D animation is now much more popular because it is widely used in advertising. Another thing I find that is more present in digital art is this blending of fine art and commercial creativity, which is pretty much connected to what Andy Warhol did, or now Takashi Murakami and Jeff Koons, for instance. For someone like me, who works with commercial projects as well as my own artistic practice, this is quite interesting, and to be invited to a fine art exhibition as a digital artist is something that the 13-year computer gamer in me finds really amazing. Digital art is definitely becoming art. It should have happened 20 years ago, but it’s okay.

“I think Niio is great. I feel that you have a deep appreciation and understanding of art.”

How do you see a platform like Niio contributing to this popularization of digital art?

I think Niio is great. I’d say that’s why we connected so well early on, because I felt like you had a deep appreciation and understanding of art. And if you’re guiding this platform, you’re gonna take it in the right direction. The way the artwork descriptions are written, the way everything is laid out, is the way a gallery would lay it out. I also value that the artist’s opinion, or vision is involved in the process. I’ve been approached by other platforms, but I didn’t say yes to a lot of things because I felt like they were mainly a business. Too much of a pure business approach to art. And I think that what you all are doing at Niio is really what the artists are trying to do.