Pau Waelder

Kaya Hacaloğlu (Ankara, Republic of Türkiye, 1975) is an artist who works in video and photography, experimenting with live cinema, documentary, and video painting in individual projects and collaborations with other artists and creators, combining video with literature, poetry, music, painting, and performance. With a group of artists he developed the projects Mugwump and Cotton AV, consisting of live cinema performances combining found footage with electro/acoustic and atmospheric music. His work has been exhibited in international art festivals and biennials in Istanbul, Zurich, Rio de Janeiro, Berlin and many other cities.

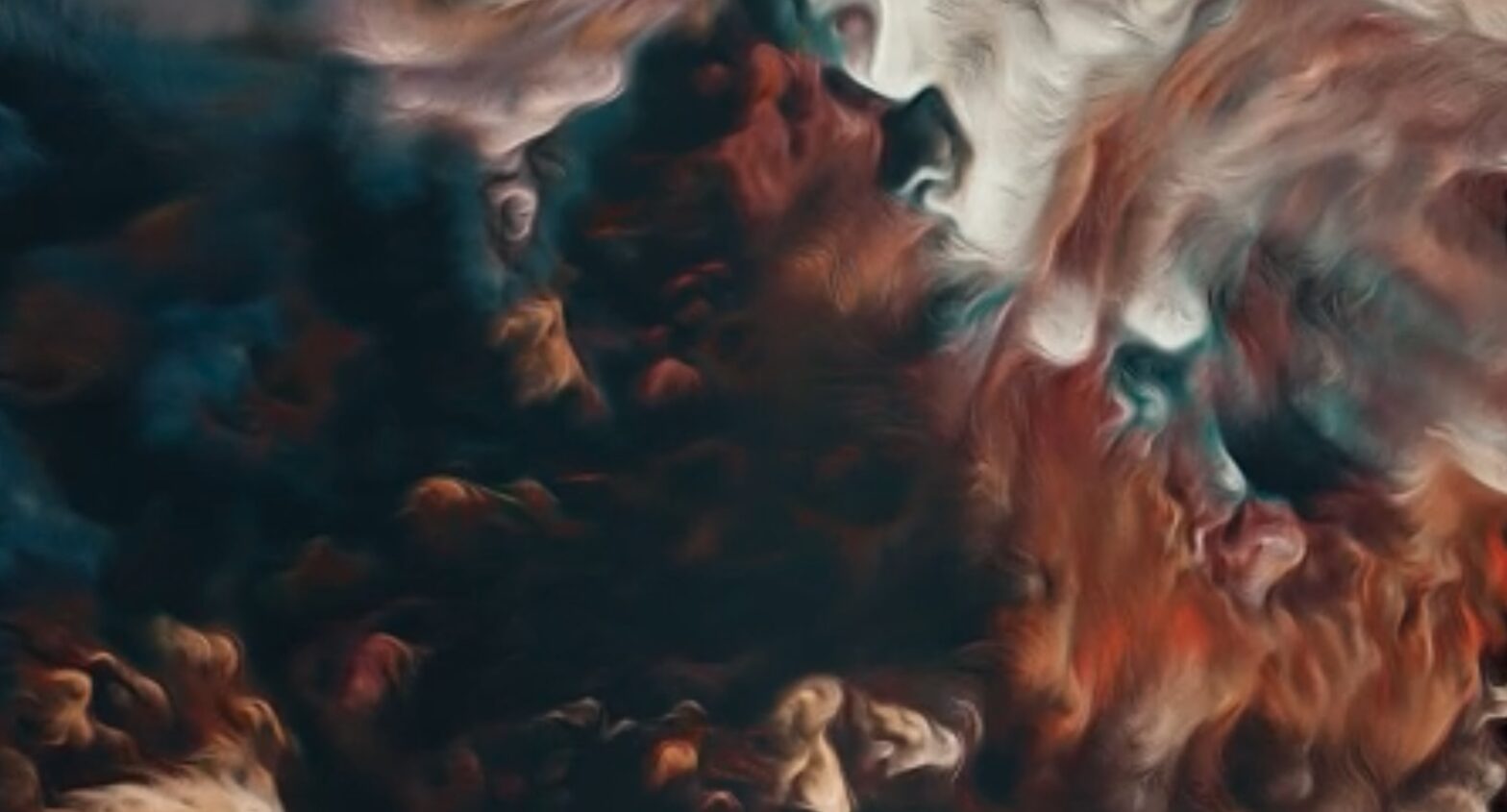

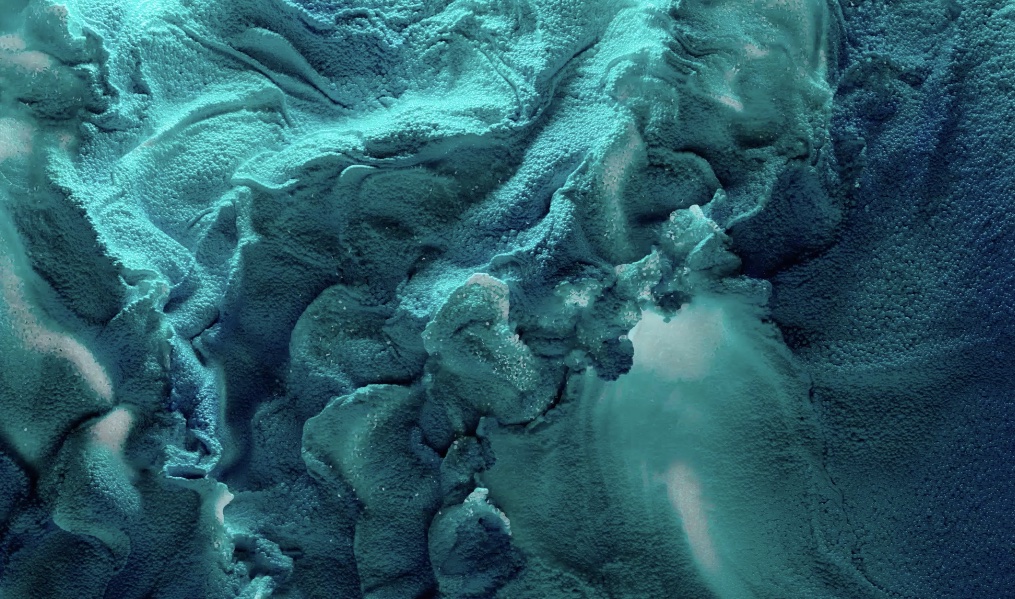

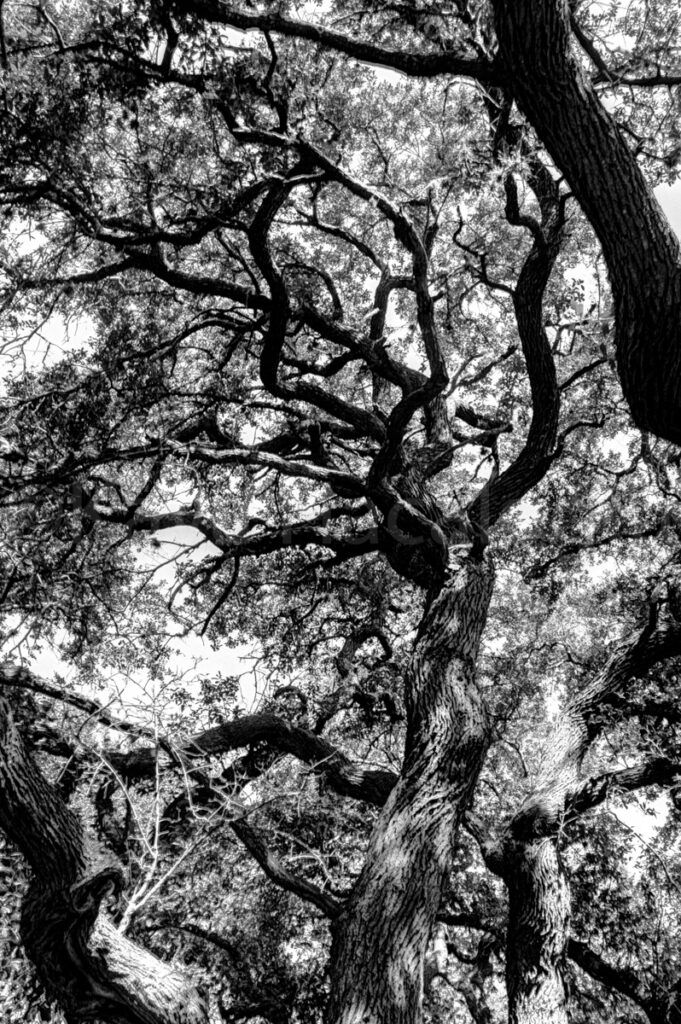

Hacaloğlu recently presented on Niio the series Pensive Tree, a photographic project that merges images from a plane tree standing at the entrance of the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul and a madrone tree in Austin, Texas into an ever-changing, flowing abstract composition that evokes multiple states of matter. Hacaloğlu chose the term Agâh to describe this morphing shape, a word that in Turkish and other languages means “aware,” or “knowledgeable.” In the following interview, he discusses his video and live performance work, the making of Pensive Tree and the inspiration he has drawn from legendary filmmakers.

Explore the Pensive Tree series by Kaya Hacaloğlu

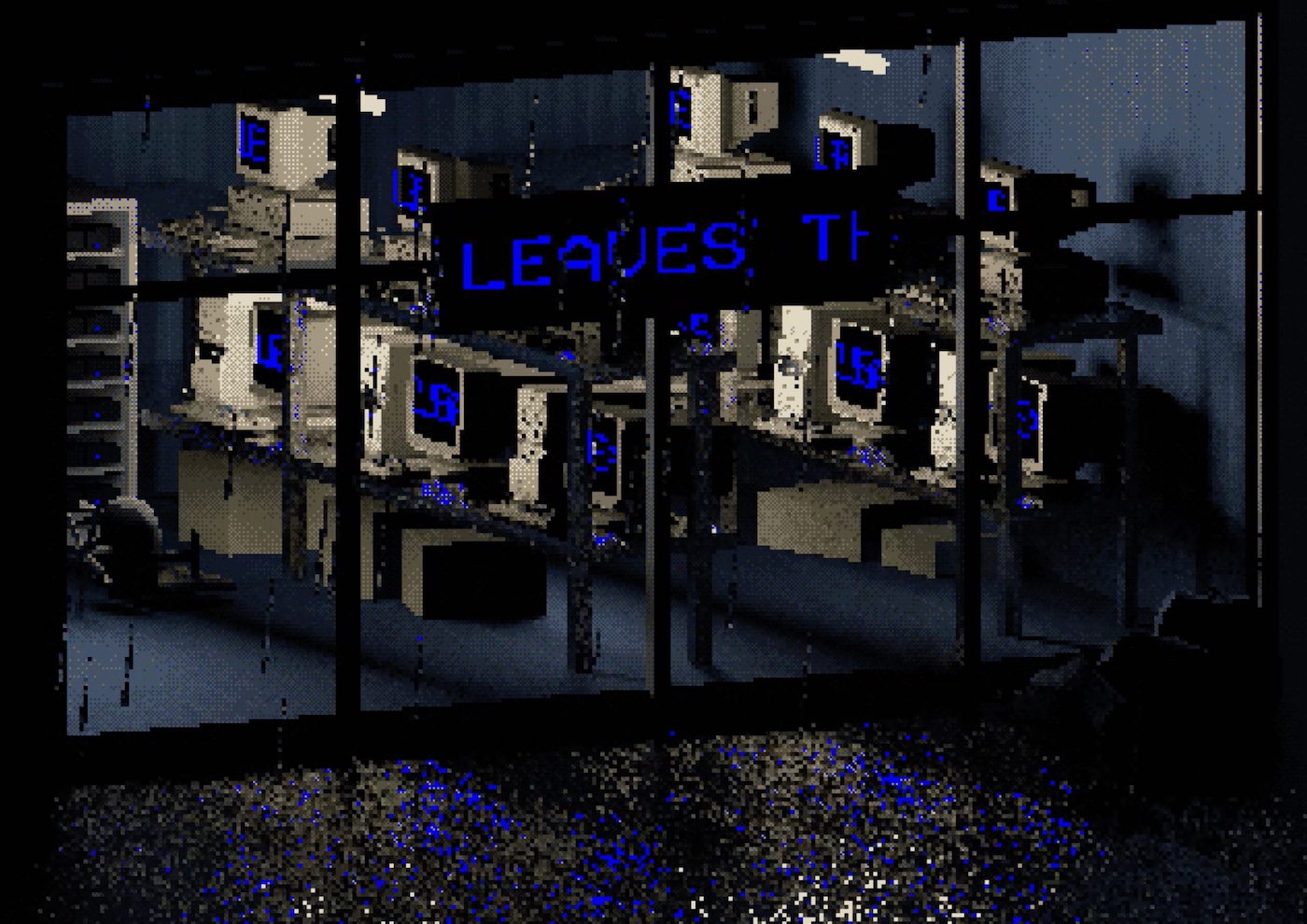

Kaya Hacaloğlu. Pensive Tree Fluffy Tissue / Agah, 2022

Your background is in cinema studies. How has the cinematic narrative influenced your work? What has driven your transition towards abstract or semi-abstract works and to video paintings?

The cinematic narrative gave me a taste, an ability, and an interest to comprehend a ‘language’ which comes with a long history of collective creation. It opened a door which influenced me to get together with other cinephiles and people of interest in creating work.

I regard cinema as a containing medium.

The quintessential auteur who has made the leap from cinema to the lands of deconstructing his own visual narrative films and projecting them in rooms and cisterns would be Peter Greenaway, whose techniques and abilities are particularly influenced by art history and classical paintings. Other filmmakers that have profoundly influenced me are Chris Marker, Derek Jarman, and Jean-Luc Godard. Marker’s approach into making a film, for instance La Jeteé, is made of a series of still photographs as opposed to filming them with a film camera by taking 25 photographs a second. He therefore plays with the sense of motion in film (although motion appears one time and only briefly at a certain point in the film.) Marker started in the movement of Cinema Verité, which takes video journalism approaches to everyday street life in Paris. Godard’s and Anne-Marie Miéville’s ways of editing and implementing found footage, archival images, sounds, music and narration, add a sense of belonging and nostalgia to the cinematic narrative, connected to a certain moment of the history of the 20th century. Jarman’s methods of multi-layer editing using video-synthesizer and his experimental approach into dance, queer cinema and his brave character have made him a landmark in Cinema culture. And of course Guy Debord and his slogan “le monde a été déjà filmé, il s’agit maintenant de le transformer:” The world is already filmed, it is time to change it. All of which I believe belongs to the tradition of filming and projecting that is part of the influences of cinema in my work.

“As Guy Debord once said: The world is already filmed, it is time to change it.”

Working a little bit at the University’s local television station channel 2 and watching displays of student works of the video art department’s ASTV is what drove me to study cinema and later take video classes at the Art School. The works I have come up with during my first years of learning were not exactly abstract works, at least the ones which got completed, but planned-constructed scripted works which were made in the university’s facilities. These works were very structural with usage of intellectual property. My transition from the realm of cinema into studies of non-narrative video making came after a work I have made mixing super8 and miniDV footage through the use of my digital NLE station at home in 2001.

In your video work one sees an attention to everyday life but also experiments with overlaying of images that lead to quasi abstract compositions, particularly Cotton AV which seems to be a precursor of the series we now show on Niio. Can you explain the process behind Cotton AV? How would you say this work relates to Pensive Tree?

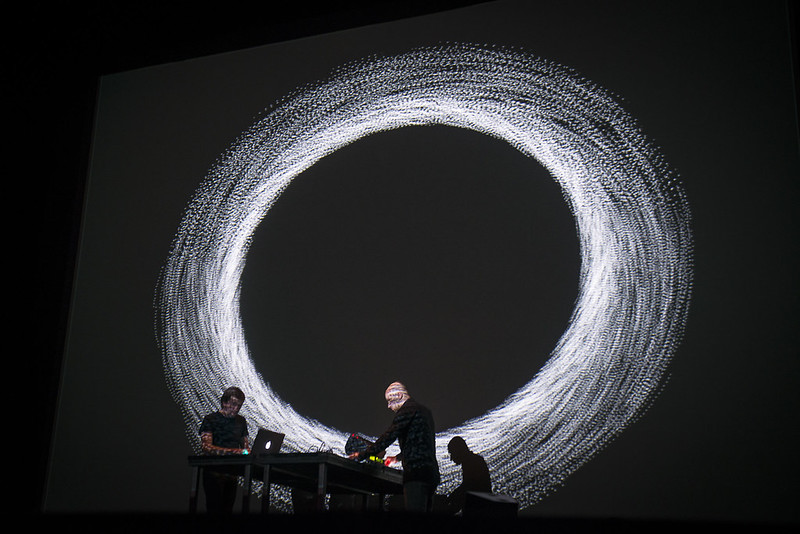

Cotton AV and its precursor Mugwump were made, as you say, by combining materials taped by Ozan Akıncı and myself and materials from public archives and footage from movies. Clips were created, looped in the most perfect possible way which were later fed to a software running on a laptop connected to a projector. By the time we started Mugwump none of us owned a laptop, and as the music was also live: there was a band of two musicians on stage, Şevket Akıncı and Korhan Erel, and a vocalist. We recorded the finished material on a DVD and connected a DVD player to the projector. As the band was playing live, starting and pausing at a certain time was crucial to keep the music synchronized with the images, which we had to do manually. We played mainly on a theater stage in Galata called Perform. Ozan got himself a laptop and as I was already used to being on stage and feeding loops, downloading loads of materials through eMule for my VJ mentor Exiled Surfer, we started using a software called Grid quite quickly. As we moved on I had a laptop and a V4 Edirol video mixer and were able to cut and fade between each other’s machines and mixes. Cotton AV had its last show at VJFest in 2012 organized by Burcu Gündüz, and ended after having performed with Gevende.

Cotton AV and Pensive Tree may seem to be connected but are in fact quite different in their production and concept. Cotton AV is a group performing live on stage, whose visuals are created on-the-fly and whether or not they are being recorded they are just like live-music, which means they will never repeat themselves the exact same way but have been improvised. Pensive Tree is a series of works. Each work is a continuing display which starts and ends. And is not necessarily a loop. It is not a collaboration but made during a different time, in the presence of Leyla Atavi who was there as both a muse and an inspiration, she is a graphic designer.

I first saw Framed digital art at a coffee shop in Moscow in the year 2010 at the commemoration of the famous poet Nazım Hikmet as we were performing with the team that created Mugwump. The screens were as big as iPads and were framed. Various softwares were also coming along and methods of projections in clubs especially had moved along which were tiresome, at times. I had an idea of using a screen as a mirror and implementing algorithms to create effects similar to those on Instagram, but that didn’t progress. By the time I started working on Pensive Tree I found people who created their own software, used RasberryPi microcontrollers and provided complete instructions on woodcutting and fitting a monitor into a frame for displaying still or digital video. There have been previous encounters such as the famous fireplace video which I first saw in Switzerland.

“Photography is a containing medium, an archive of a certain moment a fragment of a place in time. It has a natal relation with reality.”

Your photography work is strongly inspired by nature and also plays with textures and blurs to deconstruct the image and suggest a painterly composition. Which is your approach to photography? How does it relate to your video work?

Photography is a containing medium, an archive of a certain moment a fragment of a place in time. It has a natal relation with reality. It is made to replicate what the camera is seeing, thus what one eye is seeing is shaped to be seen and interpreted by many. I think of it as a womb which contains the infant prior to giving birth and where its child comes into encounter with light, as the most extreme example one can give as its relation to reality. As being begotten with the source of light. Just as, in some eastern cultures it is treated so sacredly. My brother during his trips to the Far East told me of some people who wouldn’t let him take their pictures as they thought their souls would be stolen. My relation with the camera and especially the question with the subject has somehow become an ethical matter, and questions about quasi experiencing the present, the happening has led me to nature and visual compositions.

I do not have a certain approach in photography. Looking and capturing is a certain skill which has to do with the correlation in respect to the human senses and the refinement of the experience and the person who experiences. The subject behind the works in the Pensive Tree is a photograph of a tree. The essence is a photograph started progressing through circular motion, and advanced its way with changes of the image’s pixel points and alterations in the duration and colors of the pixels that gave its textural and blurry forms and painterly character through the utilization of computer software.

Kaya Hacaloğlu. Pensive Tree Dervishes Adrift / Agah, 2022

You have collaborated with different artists, including writers, poets, musicians, and performers. Can you describe these collaborations? How have they contributed to shaping your artistic practice and the subjects you address?

The collaborations helped me to enhance my skills in editing and shaped my personal approach to the creation of later works. They have given inspiration and also reasons and responsibilities. It would have been impossible for most of the underground or non-mainstream works in Türkiye to be made if it was not for the sense of solidarity and companionship here in Türkiye.

An example of a collaboration I would like to give is from a performance that I have organized for the ending and closure of the first screenings of the works of Pensive tree. The exhibition took place in 2019 at the Taksim Art Gallery, an ancient water cistern, as part of the Istanbul International Art Biennial. The renowned Istanbul Biennial, which is sponsored by the municipality, features the work of numerous artists, mainly in the form of painting, sculpture, photography, fabric art, and installations. The new Taksim Mosque was being newly built right across the Ataturk Opera House. The closing performance consisted of guitar player Şevket Akıncı, musician Özün Usta who improvised music and artist Eymen Aktel who painted on a canvas while I was projecting or mixing works of the Pensive Tree series. A line I wrote, “I hug where you stand out, in the shadow of what is called admiration, I rest.” was read by Eymen who improvised spoken word along the show.

“I would say that the video and digital art scene in Türkiye has evolved into a very rich and confident art scene.”

Can you tell us about the video and digital art scene in Türkiye? What is it like, how has it evolved in recent years given the growing presence of art fairs and international events?

The video art scene started with a few people many years ago who voluntarily curated artists who had limited ways of displaying their works. This was before Youtube. I would recall VideoIst, and other collections such as Turkish Delight by Genco Gülan and other camps back in the 2000’s where shooting and editing video was taught and required collective work such as Barış için Sinema (Cinema for Peace.)

Displaying digital video requires expensive display equipment like a Digital Panel or a Digital Projection. Along the years many organizations with panels with artists and curators, and solo shows the scene has made its peak I would say with the help of sponsorship. Many Turkish artists are in the international arena. Mappings, public projections to historical monuments and the usage of ancient spaces are being organized for exhibiting digital artwork.

Your work is present in several online digital art platforms. What is your experience with the digital art market? Which opportunities and challenges do you see in the way art is distributed and commercialized nowadays?

My experience with the digital art market is due to the medium’s properties, the ownership, “re-production,” and maintenance of the artist’s rights of the “original” artwork. It is a challenge for the art market to introduce digital artworks as there is a strong competition from “static” artworks such paintings and sculptures. But I believe the growing acceptance of digital art is coming through large installations in public spaces, and not only in ticketed entry shows. The main issues for the future of digital art, in my view, are the accessibility to the artworks, the fairness in remuneration for artists, and of course that the art is properly presented.

Digital art can be treated as wall art or framed art now and it is making its way into homes. I remember one platform which displays the works of painters throughout the history of art on a vertically mounted ‘television’ and this example only can show us how much it has evolved throughout the history of print making.

“The issue for the artist is to have their work exhibited and recognized. The way digital art can be distributed is already here, it is a technical matter for it to be installed and displayed almost anywhere.”

The opportunity is for the art is to be visible. The invention of NFT granted the digital artwork an ‘original’ status because of its copying properties being hundred percent undetectable, a digital artwork becoming a digital token marks it as valuable.

The issue for the artist is to have their work exhibited and recognized. The way digital art can be distributed is already here, it is a technical matter for it to be installed and displayed almost anywhere. The challenge is how will it be creating a revenue for the artist and how will the preservation of the work be possible. Is it ok for some works to be available publicly or do they belong to private institutions, as video art has been treated and distributed as videotapes or film?