Domenico Barra and Pau Waelder

DISØRDINARY BƏAUTY is an ongoing art project by Domenico Barra that explores ugliness through glitch art. The project has been developed as a series of NFTs, with a new phase taking place on Niio as a work in progress, in which the artist will periodically upload new artworks and accompanying documentation. Here in the Editorial section, we’ll publish email exchanges bringing light into Domenico’s creative process and the ideas and influences behind this project.

Follow Domenico Barra’s work in progress on your screen in DISØRDINARY BƏAUTY: art canon

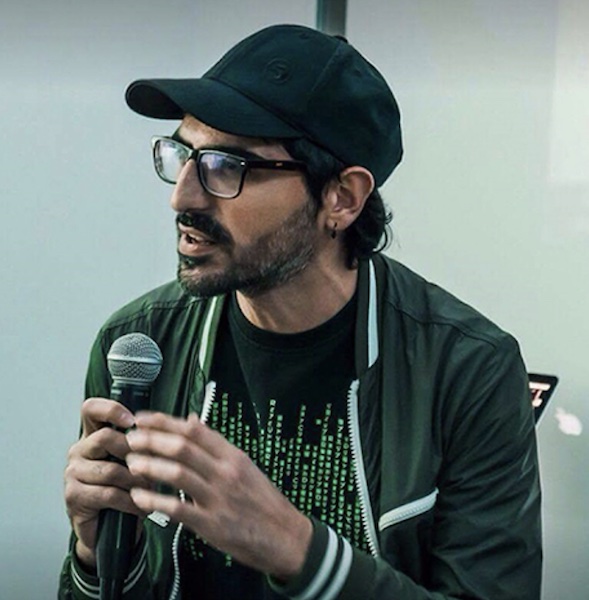

Domenico Barra is an Italian artist, educator, and curator whose work delves into the aesthetics of glitch art, “dirty” digital media and Internet cultures. He creates images, gifs, videos, and installations through a variety of techniques aimed at generating errors in the processes carried out by hardware and software to create the contents we experience on screens. In 2017, he adopted the nickname Altered_Data, inspired by the realization that online data is gradually shaping and manipulating our identity and behavior, and the fact that he was born with an immune system disorder.

He is the creator and art director of the online project White Page Gallery/s. a distributed and decentralized art network and community. In 2021, he started minting his works as NFTs and is now an active member of the NFT art community, selling his work on Ethereum and Tezos. He teaches glitch art and dirty new media at RUFA – Rome University of Fine Art. His work has been exhibited, among others, at DAM Gallery (Berlin), Galerie Charlot (Paris), Digital Art Center (Taipei), online at the Wrong Biennale and with Arebyte, and in many other galleries and cultural art events worldwide, on the internet and the metaverse.

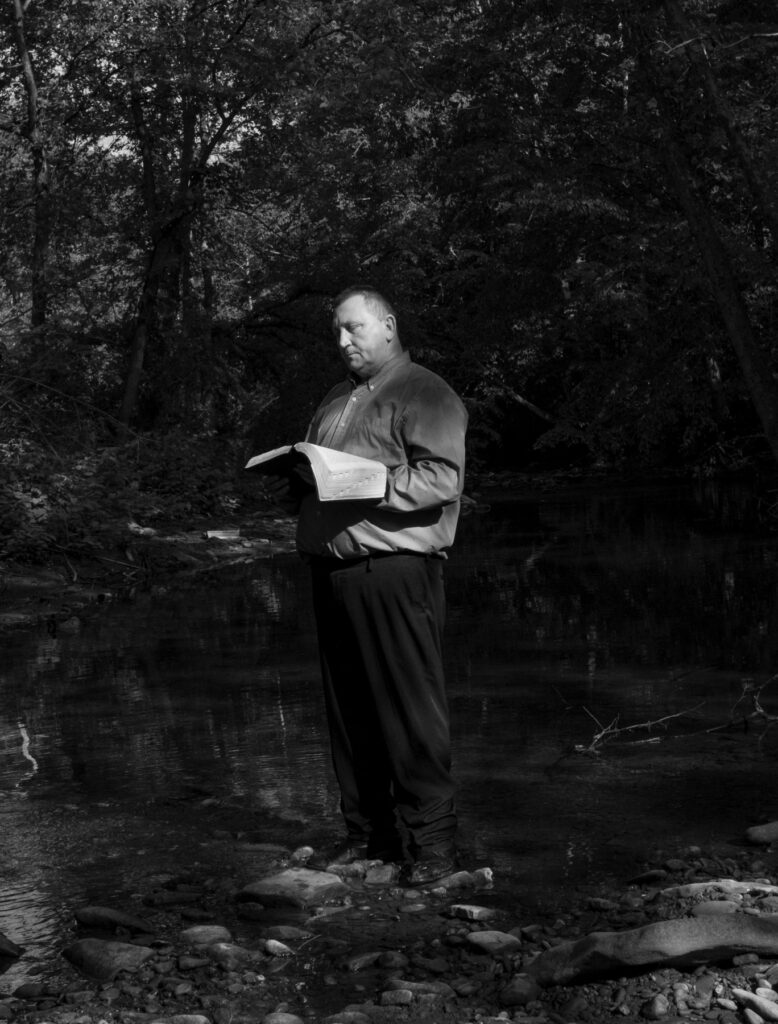

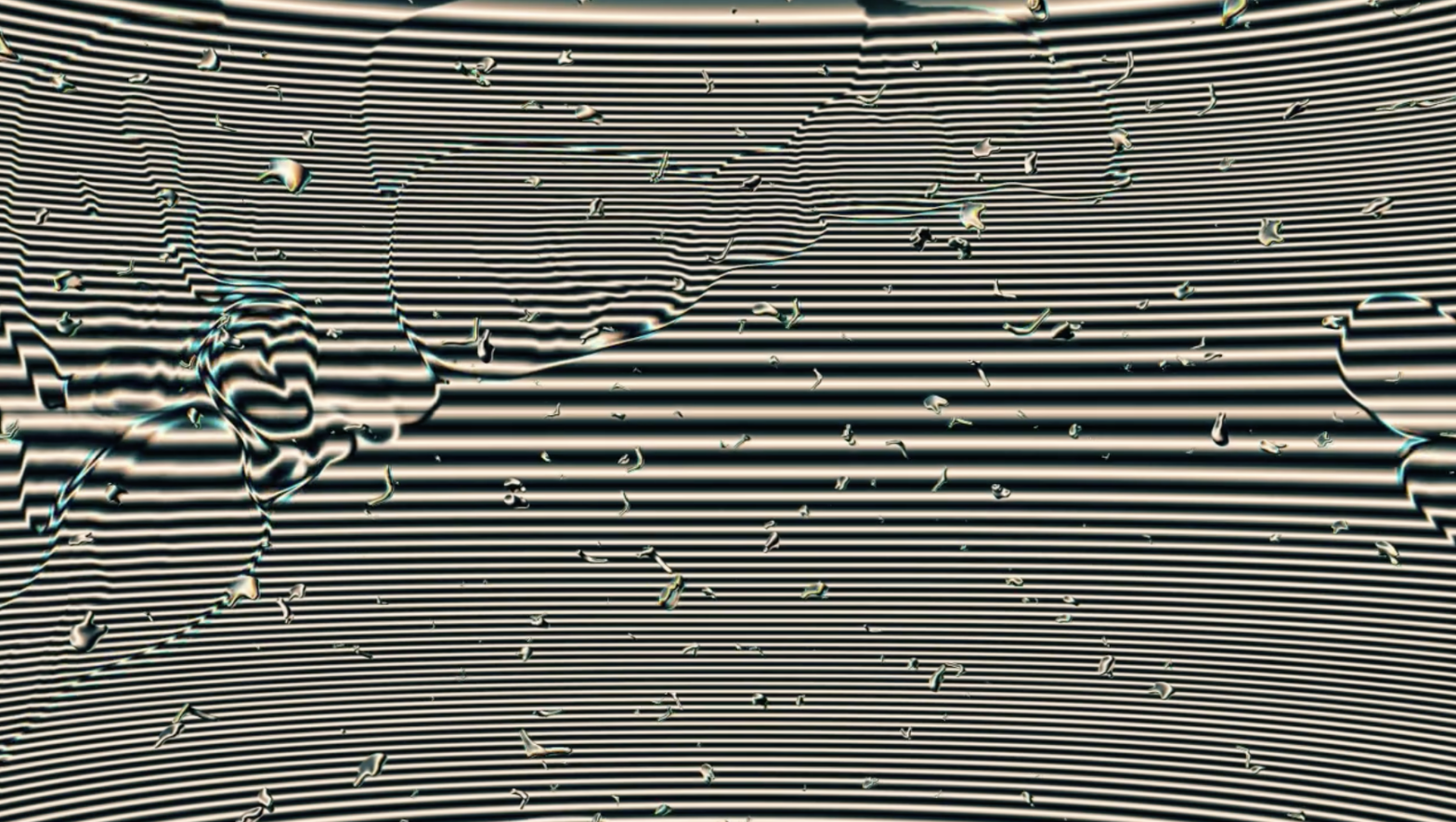

Domenico Barra, DB a̶r̶t̶ ̶c̶a̶n̶o̶n̶ | a̶ ̶b̶e̶a̶u̶t̶y̶ ̶i̶n̶ ̶v̶i̶o̶l̶e̶t̶, 2023

First ɛʍǟɨʟ exchange

from: Pau Waelder

to: Domenico Barra

date: Feb 19, 2023, 12:23 PM

subject: Re: Disordinary Beauty Work In Progress launch

Hi, Domenico!

I’d like to start publishing our series of exchanges in the Editorial section this week. For the first exchange, I’d like to shoot this question:

I have read several interviews in which you describe how you got into Glitch Art and the artists that inspired you. We’ll get into that later, but I’d like to ask you: what does glitch mean to you now, in the midst of growing AI creativity, after the NFT boom, and in relation to this particular project about beauty?

from: Domenico Barra

to: Pau Waelder

date: Feb 20, 2023, 6:47 PM

subject: Re: Disordinary Beauty Work In Progress launch

Hello Pau,

Ten years ago, I began making glitch art, and since then, glitching has evolved and taken on different meanings that are all related to our imperfect nature. I’m enthusiastic about AI and have been exploring with other glitch artists what a glitch within AI means and how to trigger it. However, since AI networks and ƧYƧƬΣMƧ are vast, closed, and not very transparent, most discussions are about finding vulnerabilities to exploit. A glitch within AI may not look like the digital glitches we’re accustomed to for sure, but Nick Briz advanced the suggestion that a glitch within AI could still be considered as something unexpected. For instance, AI’s inability to accurately depict hands can be considered a glitch.

A glitch within AI may not look like the digital glitches we’re accustomed to. For instance, AI’s inability to accurately depict hands can be considered a glitch.

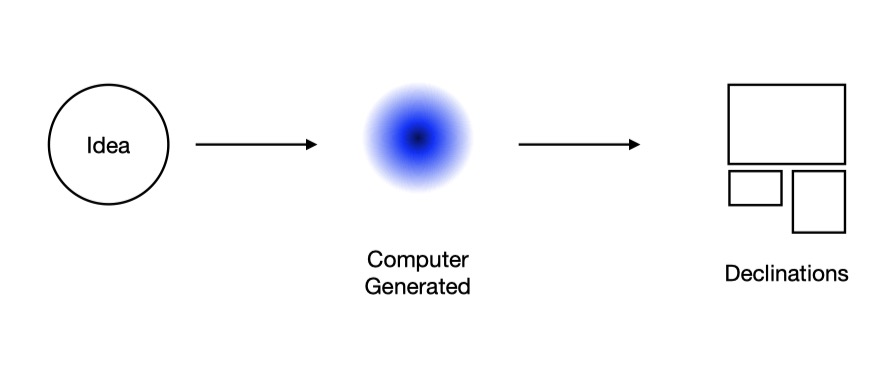

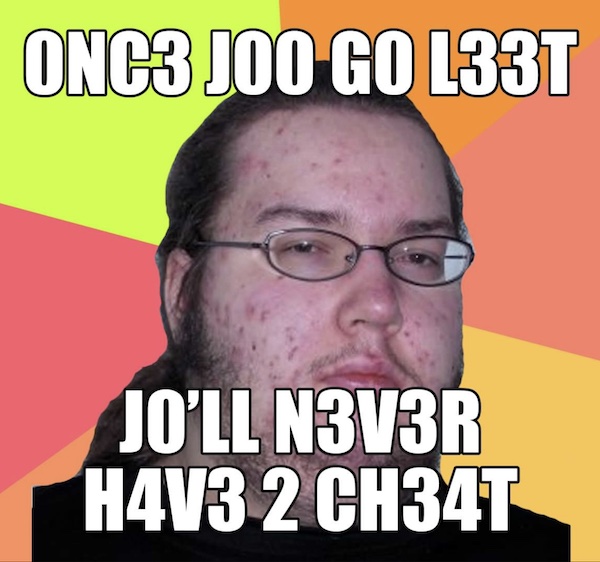

My personal approach takes inspiration from Databending, precisely incorrect editing. I started inducing short circuits in AI’s word-based processing by using prompts inspired by L33T SP34K language. The results are interesting and absurd images that could resemble some sort of twisted memes. In databending, by injecting random values or deleting/substituting some data values in image files using hex editing, the software organizes the data according to the standard file format. I played with altering prompt word input and influencing AI’s interpretation to create random “glitchy” image associations, resulting in unexpected and interesting outcomes.

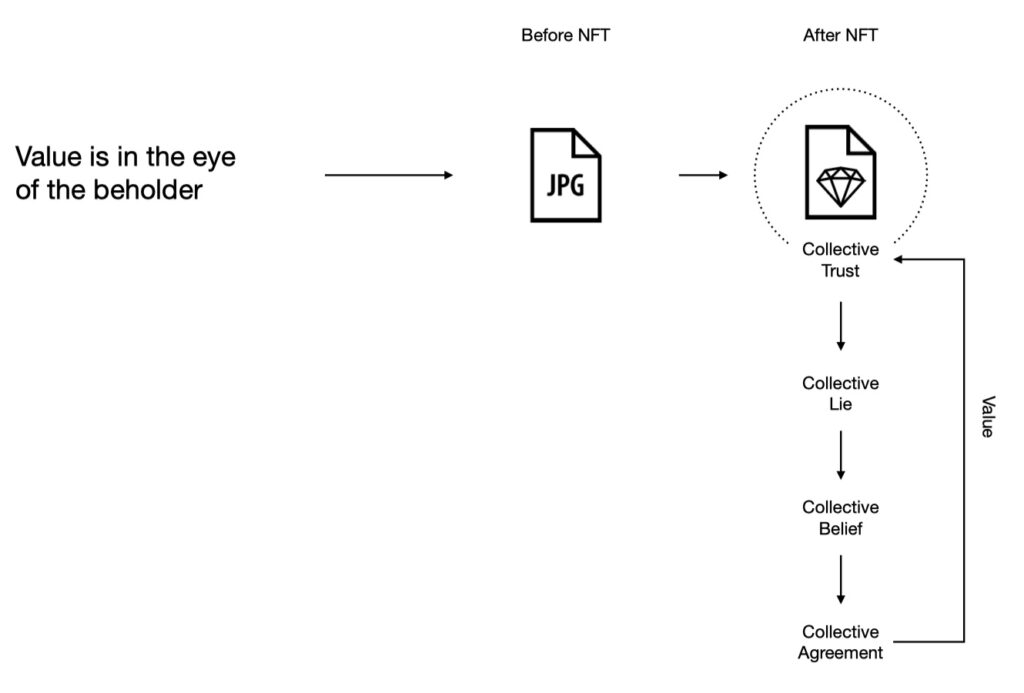

NFTs offer an opportunity for experimentation in the imperfect art market, but the vision of doing things differently is gradually fading as they are becoming more “traditional”. Decentralization requires a cultural shift in personal and community values, and Web3 still heavily relies on Web2 social media, hindering social value and the ways value is created and artists promoted and glorified. Glitch art emerged in crypto art thanks in part to X-Copy‘s market success and leadership. There is also a marketplace called Glitch Forge that is entirely dedicated to glitch works of all sorts. Glitch art and styles are popular online and in NFT/crypto art, with artists reclaiming their space through the #postglitch aesthetic, especially in response to the status quo. The most famous probably is “Trash Art”, a movement of artists using glitch apps and filters excessively and with a strong amateur style in response to the anonymous artist PAK who declared that artists using glitch effects for their art were not real artists, leading to the creation of the trash art movement.

Confused? Try this quick intro to Glitch Art:

NFTs offer an opportunity for experimentation in the imperfect art market, but the vision of doing things differently is gradually fading as they are becoming more “traditional”.

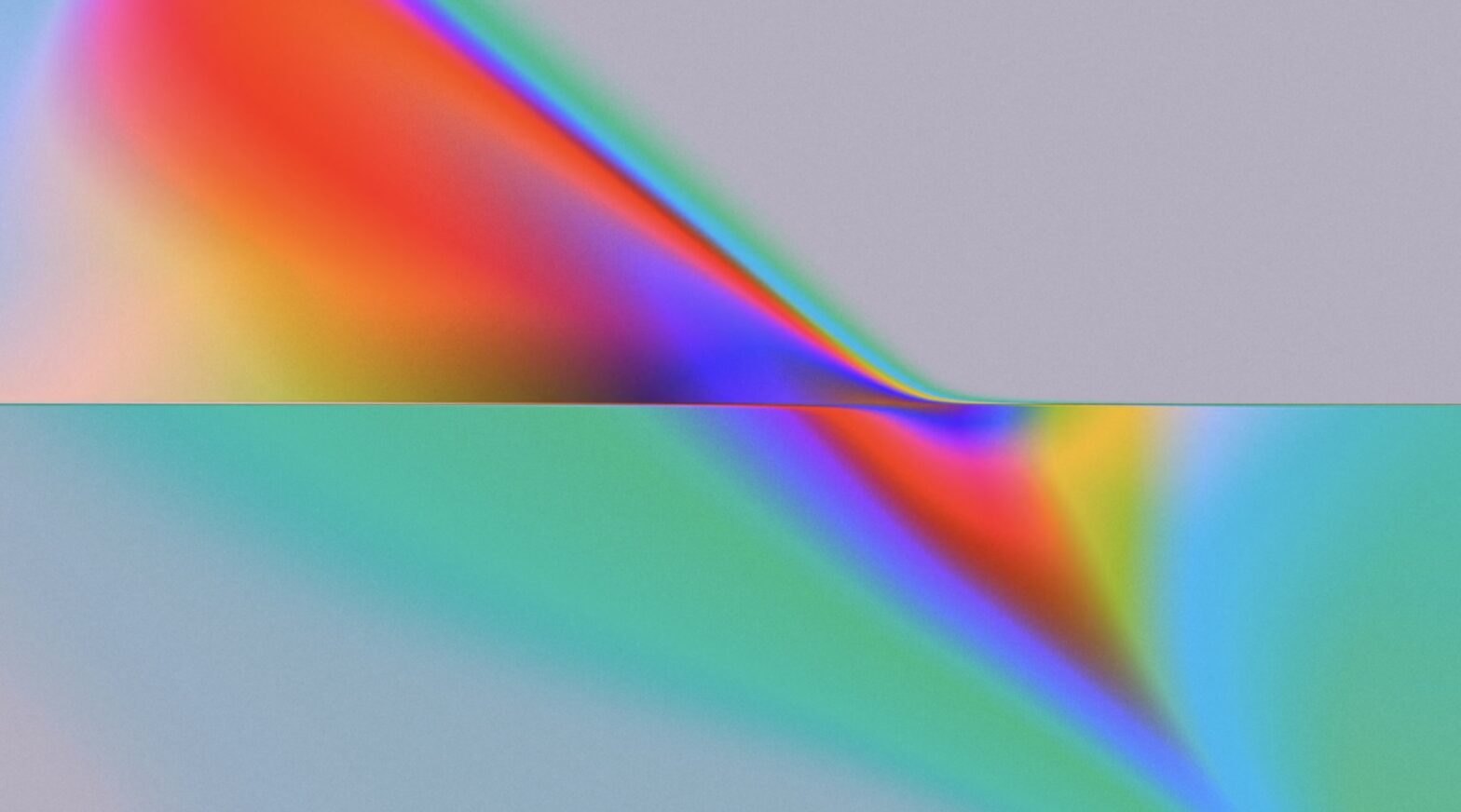

Disordinary Beauty was born in the midst of the NFT boom and the emergence of new creative apps. Specifically, there was a growing interest in generative art among NFT collectors. It started as a personal experiment when I decided to try out some new generative glitch scripts. While browsing Instagram, I came across a selfie by one of the many influencers on the platform. As someone who has always struggled with the cult of image, beauty, and success perpetuated by Instagram, I decided to use the glitch scripts to slice up the selfie, surely inspired by The Blade Artist by Irvine Welsh that I had just finished reading. I continued this practice by creating one glitch portrait per day, every day, using a different influencer’s selfie each time.

As I continued to select selfies to glitch, I noticed that there were many common features among them such as the lighting, saturation, head position, and gaze. It was as though there was a programmed formula for shooting the perfect selfie. Through further reading, I discovered that the pose and formula adopted by influencers were not just for the sake of appearance, but also to make their photos easily recognizable by Instagram algorithms, thereby gaining more priority in the platform’s feed. This led me to see the glitch scripts as a way to reprogram and decode the selfies, ultimately erasing the image itself. This became a sort of redemption of the atypical, the imperfect, and the weird.

The pose and formula adopted by influencers in their selfies were not just for the sake of appearance, but also to make their photos easily recognizable by Instagram algorithms.

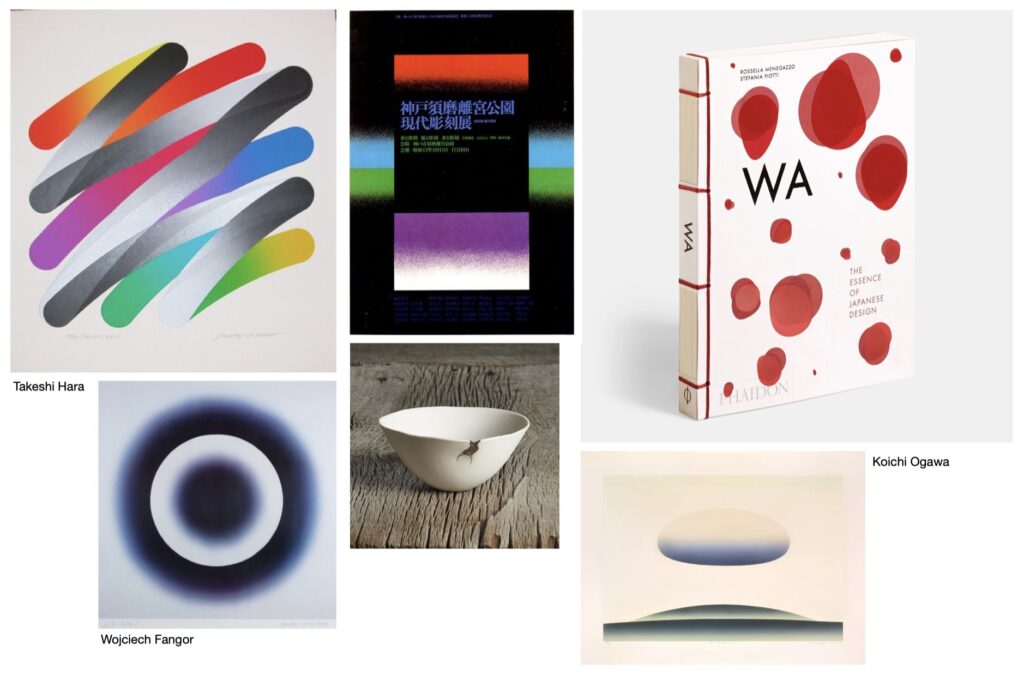

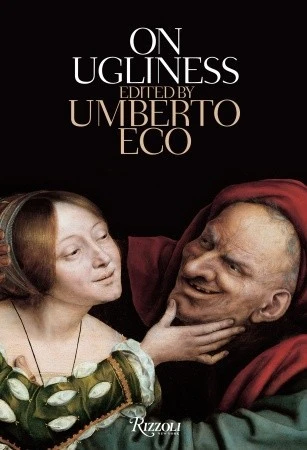

My interest in the concept of beauty on Instagram led me to read ʊʍɮɛʀȶօ Eco‘s On Ugliness and expand my exploration into the meaning of beauty and ugliness in art, and how it has been used to create new biases towards individuals who do not fit societal standards. I wanted to push things a bit further and delve into these concepts in the realm of AI as a sort of social consciousness, prompting image-based conversations with AI using ChatGPT so far and then also disrupting the perception and formatting of beauty in classical art.

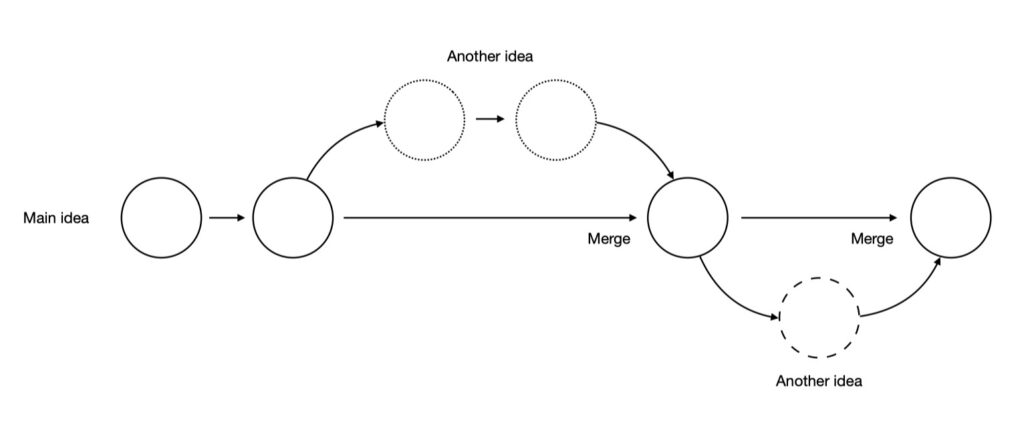

Disordinary Beauty is now divided into three stages. The first stage, “BÆUTY IZ CH∆ØZ,” involves glitch erasure actions on influencers’ selfies. The second stage is “Conversation between AI and I” on topics related to beauty, ugliness, art, and society. The third stage called “art canon” will happen on Niio and involves bringing chaos into the harmony and beauty of classical artworks, and the experience of the viewers.”

Sincerely,

d0/\/\!