Pau Waelder

Jaime de los Rios (Donostia/San Sebastian, 1982) is a visual artist and programmer, founder of the open laboratory of art and science ARTEK[Lab] (2007). An expert in free software and hardware, he has developed over the last decades a body of work that blends contemporary art, science and technology, creating immersive environments and generative works, often in collaboration with other artists, scientists and engineers.

On the occasion of his solo exhibition “El problema de la forma” at Arteko Gallery, we present in Niio a selection of his recent digital works and conduct this interview in which we delve into the career, work processes and inspiration of the Spanish artist.

Explore a selection of artworks by Jaime de los Rios in On The Problem of Form

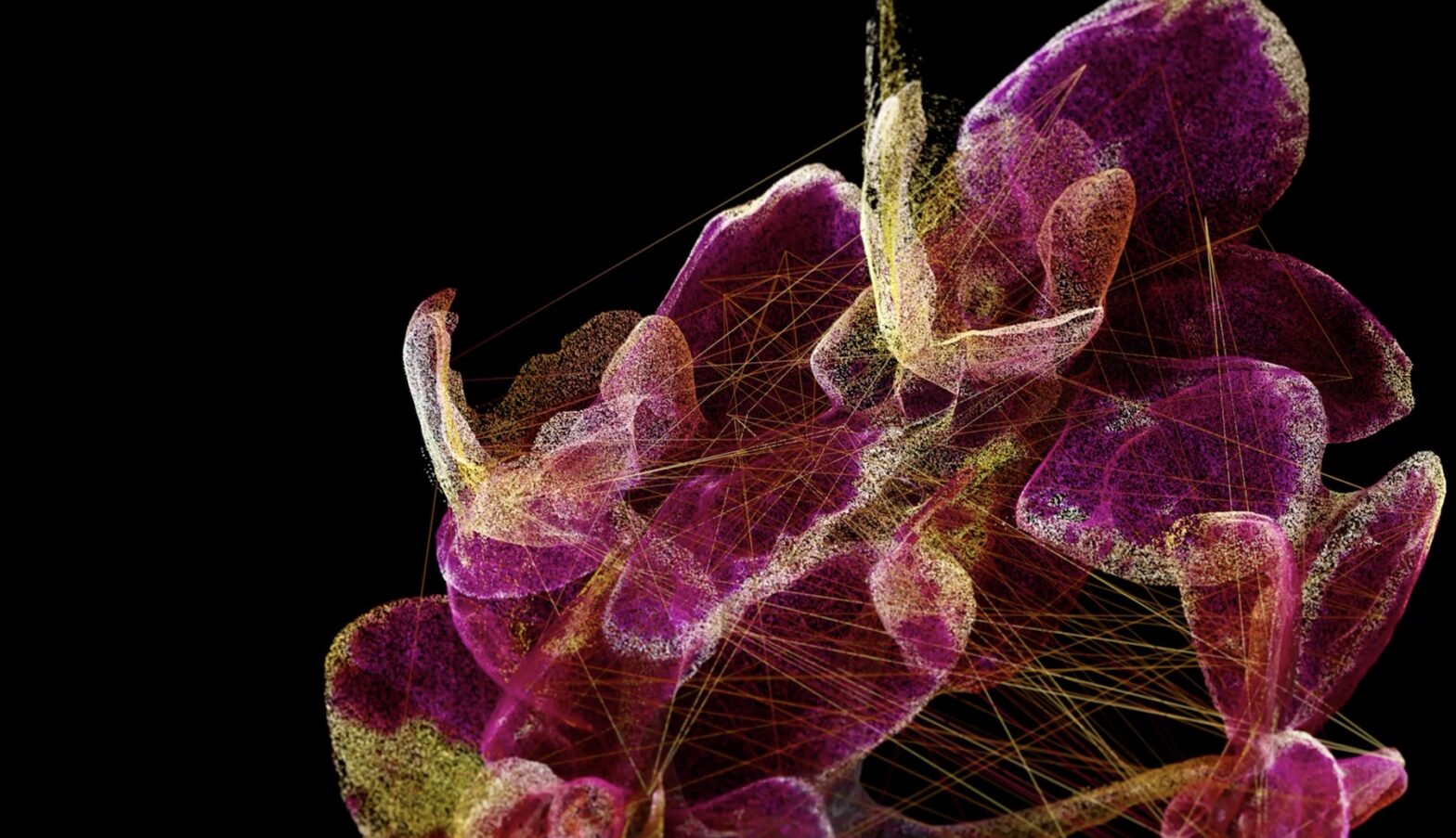

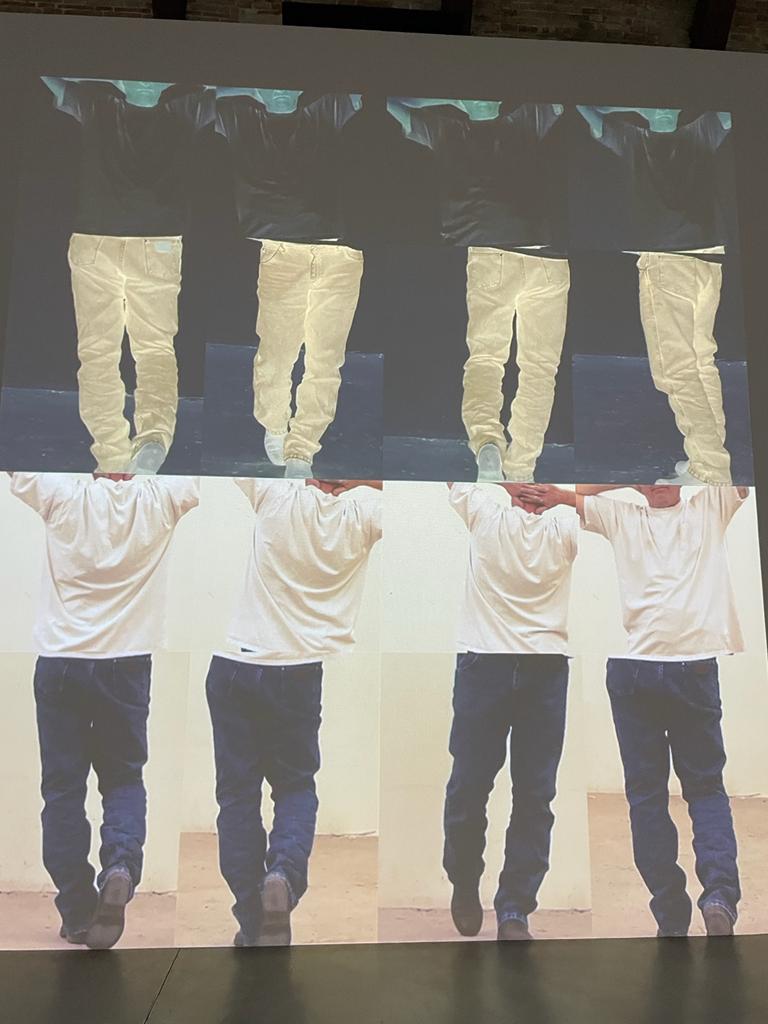

Jaime de los Ríos. LeVentEtSaMesure I, 2024

As a visual artist and programmer, you unite the two essential aspects of digital creation. What led you to develop your career in this field? Which aspect tends to prevail, the one that seeks a particular aesthetic expression, or the one that seeks to experiment with new technologies?

I consider that creation is intimately linked to the paradigm that the artist inhabits. In my case, different contemporary aspects intersect that have led me to use new technologies, as well as the aesthetics of these technological times. I did my studies in electronic engineering and I was educated to successfully manage the technical capabilities of my time. However, in the process of learning, certain desires and results have come in the way. These were not initially desired, but they responded to a philosophy or a concern. I remember well when I had to program an automaton that controlled a traffic light and I forced it to make a certain error that made the three lights blink in a randomized cycle. This reminded me of the famous movie “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (Steven Spielberg, 1977) and how it used the language of sound and color, with the notes Sol re Sol. There I realized that to control the technology of the moment was also to be able to use the best tools in a critical and aesthetic way and that in such a technologized society artists have an important role to reconfigure or offer a political view of the situation.

I work mainly with algorithms. I don’t always do it from a programming language but the logic is the same. I compose simple systems that are governed by different equations: these combinations make the system complex, quantum we could say. In its infinity I cannot know how the system will behave at a given moment but I can frame its behavior. It is like sculpting infinity. When handling these systems, I navigate among the mathematics themselves and it is these that make the possibilities emerge that perhaps would never have been in my head if I had thought about it from the beginning, so aesthetics and technology are absolutely linked to each other.

In your work there are influences of geometric abstraction and the work of pioneers such as Manfred Mohr. What references have marked the visual vocabulary of your works?

Of course, Manfred Mohr, Vera Molnar, Frieder Nake…. And also the whole ecosystem of the Computing Center of Madrid, including artists such as José Luis Alexanco or Elena Asins. At the moment when these artists became acquainted with computation through the computer there is a moment of singularity that is very inspiring for me and can be appreciated in my last exhibition. The precarious resources, such as simple geometries, and yet the great capacity for resolution are undoubtedly a great metaphor for the work of these artists in their time. It is the first painting made using a computer, but it has immense poetics.

I have arrived in my work to these artists that I already knew but I have done it at a later time, after exploring the history of painting itself and activating algorithms in a pictorial way. In recent years I have wanted the work to speak of its own support and its own algorithms in a transparent way and that is why the elements I use are precisely reminiscent of that synthetic painting.

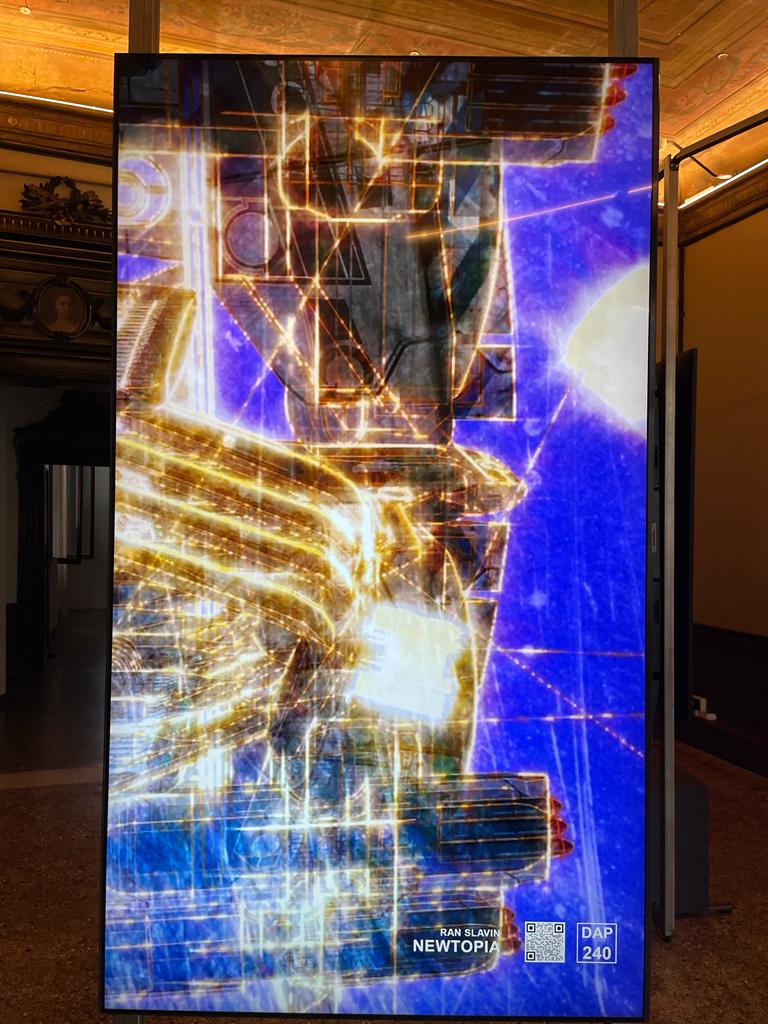

Jaime de los Ríos. FlyTheProblem, 2024

A main aspect of your work lies in the use of generative algorithms to create constantly morphing compositions, with each work being what Frieder Nake once defined as “the description of an infinite set of drawings.” What attracts you to the possibilities of generative art? What is it like to conceive of a work that does not consist of a finished visual composition, but rather a set of instructions and behaviors?

It is undoubtedly one of the great differences with respect to plastic art. Algorithms allow us to think and develop artworks that change endlessly. We work with movement, fundamentally, let’s say that so far we have a new characteristic which is rhythm and we leave behind, as if it were a curse, the texture and smell of painting.

Here there are also two types of digital artists, those who direct their creation to something they have previously thought of and others like me who navigate mathematics and in the dialogue with the algorithm itself we let emergencies flow, but then both types of artists need to conceive the work as a system, a framework of possibilities. The work is never solved but it is enclosed in a space of freedom.

The most exciting thing about this technique, I would say, is to reach the infinite in a poetic way that enables contemplation. To do this, and knowing that it is a post-editing technique, that is, it does not begin or end, we only have to look at nature, the largest infinite system that can be known. From there it is trapped into mathematics and transferred to aesthetic systems. Some artists do it in a very direct and figurative way, others use a system of color and a rhythm that we can perceive as human beings, everyday phenomena such as the reflection of the light in the sea, the shoals of fish or the choreography of birds.

“The work is never solved, but locked in a space of freedom.”

In addition to pictorial references, in your work you have explored the relationships between digital art and film, using Gene Youngblood’s concept of “expanded cinema”, and also with the electroacoustic music of Iannis Xenakis, as well as jazz. What do these connections with film and music bring to digital art, and especially to your work?

My work is an incessant search for pictorial, tactile, and sound systems. However, I rarely generate my own sound, so I use the mathematics of music to apply it to the artworks. Many of us electronic art artists work transcoding data, that is, a work can be silent and at the same time have a lot of musicality as is the case of my work on Iannis Xenakis, where I use his famous equation, the curve, which he applied on the one hand in architecture but also in sound composition, to move a series of kinetic artifacts that are like windmills. By activating a movement directly proportional to this curve and also generating a very powerful rotational sound, the whole immersive work, which is also projected, forms a universe that evokes the work of Xenakis. It is almost a scientific experiment: what would have happened if we human beings did not have the sensors to hear, and had to translate those frequencies in the form of color, for instance.

Jaime de los Ríos. pixelsunshine, 2024

Telepresence is a concept you have worked with in several projects, which have notably incorporated a complex interaction between devices, people, and spaces. What attracts you to the possibility of creating these remote connections? Based on your experience with these projects, how do you see the ubiquity of digital art through platforms like Niio, which make it easy to integrate artworks on any screen?

The telepresence I worked with is situated in time between the utopia of net art, the rhizomatic connection, and the quantum era of entanglement. It is one of those concepts that are human aspirations and that Roy Ascott and Eduardo Kac, of course, talked about and developed a lot. In the days of the Intact collective we did teleshared actions between many places around the world. The most interesting thing is that they were not based on video as in our new tools, but given the precariousness of the Internet connection what we sent was mostly mathematics. So I became an interactive beacon of light to the music coming from the SAT in Montreal thanks to the data flowing through the fiber optic cables.

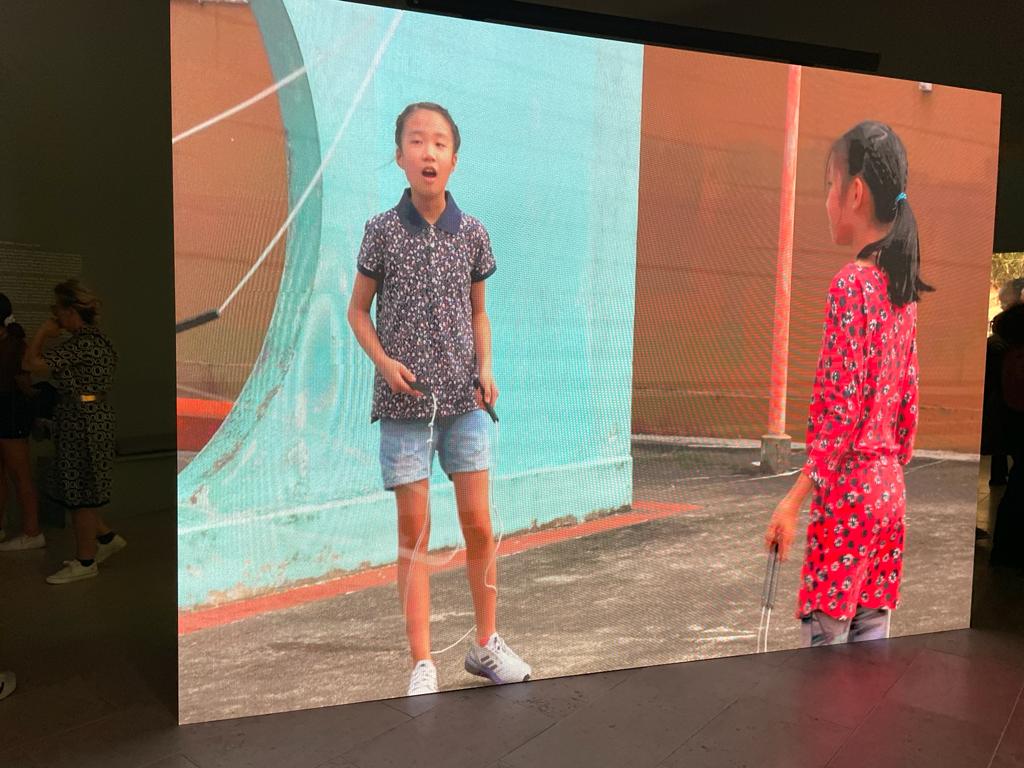

Niio is a revolution for digital art, it takes advantage of the nature of the medium and takes art out of the black box. One of the big problems of art today is that it has not changed at the pace of society, today we must be accessible and in the pockets of the user, the art lover and not exclusively in centers or institutions and galleries, which of course provide a great value to the work but limit access. Likewise, one of the characteristics that most interests me about Niio is to be able to enjoy the works in privacy, at a contemplative pace and in a space of one’s own without the pressure of contemporary daily life. Enjoying the work during different times throughout a day, a week or as long as you wish, that is the way in which art becomes great and we truly understand it.

“One of the features that interests me most about Niio is being able to enjoy the works in privacy, at a contemplative pace and in a space of one’s own without the pressure of contemporary daily life.”

Your works have occupied the facades of large buildings such as the Etopía center in Zaragoza or the Kursaal in Donostia. What are the challenges of creating a work for the public space and in large dimensions? How would you say they contribute to raising awareness and appreciation of digital art?

Besides the technical complications, because each digital facade has its own nature, what I am most interested in is to dialogue with the space, to reduce the gap between art that people feel safe with and is part of their history and digital art. Of course this is not the same everywhere. For example, in the city of Zaragoza, which is closely linked to classical art, I created a work called Goya Disassembled. It was the first work made for the facade of the art and technology center Etopia and the result of an artistic residency in this cultural institution. It was an infinite work in which the artist’s entire color palette was displayed, based on all his paintings and drawings. In most of the cities of the world this work would be a rhythm of colors, however in the Aragonese city it spoke of its history and the people who saw it knew perfectly well that these are the colors that in one way or another inhabit the city: dark, strong colors, just like the paintings that they know and love so much of Francisco de Goya.

Much of your work is characterized by collaborations with other artists or collectives. What have these collaborations contributed to your work? How does the creative process differ when you work on a piece individually from when you work as part of a team?

My artistic work has always been linked to collaboration, and I think that in general all artists working with new technologies are constantly busy! In my case I think that for better or worse I have developed a more personal line and when I have the opportunity to work with other artists in the creation, being a very hard and difficult process, it allows me to get out of my more personal line and activate other issues. If I look back, I’d say that when I work in a collective I am much more political and semantic, while when I work on my own I’m more romantic and liberated.

In any case there are different types of collaborations. When you work with different disciplines, for example in my case I have worked with musicians, we allow ourselves to be ourselves and reach something common. When you work with other digital or plastic artists you have to create a whole new space, that’s why many times you start from discussions and it’s more complicated to speak from the heart.

“When I work with a collective I’m more political and semantic whereas when I work on my own I am somewhat more romantic and liberated.”

You have a long experience in the design and technical coordination of digital art exhibitions and events in Spain, such as the Art Futura festival or the exhibition “Sueños de Silicio,” among many others. From this perspective, how have you seen the presentation and reception of digital art in Spain evolve? What successes and missed opportunities would you point out, globally?

This is a complicated question and at the same time essential to understand the contemporaneity of electronic art. I will begin by talking about the artists themselves and how they have been affected by the way of exhibiting this type of art, which is often related to spectacle and the possibilities of the future of art. Electronic, digital and new media art has been closely linked to the exhibition of new technologies and this has generated a precarious business model for artists who, by collaborating with more people, generate grandiloquent and very expensive works. The spectacularization of the medium has not served to professionalize the artists but rather the other way around, we have festivals in which we seek to be impressed by the use of new technology, and this has caused us to generate a niche, a place apart from contemporary art.

This is not bad per se, but we must enable new paths, encourage professionalization and the labor of art, with works in a smaller scale but also more linked to a personal production. This may sound a bit classical but I had the opportunity to work with the Ars Electronica archive some time ago for the curatorship of a small exhibition in Bilbao. The vast majority of artists who participated in this festival throughout its history do not create art anymore. Perhaps it is still a very young art.

Finally, I would like to add that I work at the New Art Collection and I study the work of artists in the technological field. In recent years there has been a great step forward in the field of collecting, with serious proposals from the creators that will allow new generations to enjoy this art.

Over the last two decades you have been active in the training aspect of digital art, running workshops and being part of teams in medialabs, notably as founder of ARTEK [Lab] at Arteleku. Can you give me an overview of the genesis and development of the maker and open source communities in Spain? How have the collaborative and training spaces in which you have participated influenced the development of a digital art scene in Spain? How has the reception of digital art that you mentioned in the previous question affected these spaces?

I have great memories of the first digital artists I met in Spain. They were linked to centers like medialab Prado. They were collectives like Lumo, which lived in a space of open creation, where they worked in the technological field from a political position of open source but also aesthetics. Not to beat around the bush, I will say that all this changed with the arrival of the maker movement. Being interesting and positive in the first instance, this movement took the political facet (open source, collaboration, etc.) and turned it into its emblem but left behind the aesthetic and even critical field. It linked creation to a certain machinery and it can be said that it made us almost slaves of those machines.

I lost many people along the way who, from being free researchers, turned exclusively to machines and the machinery of the market. I would say that here there is a first stage which is the hackmeeting, hacktivism as epicenter and hybridization of new ways of thinking in terms of technopolitical, cosmovisionary feminism, and then maker culture, a reductionism with neoliberal tendencies, oriented to generate a third industrial revolution linked to new economies.

“We have festivals where we seek to impress ourselves by the use of new technology, and this has caused us to generate a niche, a place apart from contemporary art.”

You are currently working as advisor and technical coordinator of the New Art Foundation, the largest collection of digital art in Spain. What challenges does the preservation of digital art pose, and how do you see the future of this type of artistic creation in terms of its permanence in institutional collections and the knowledge of its history?

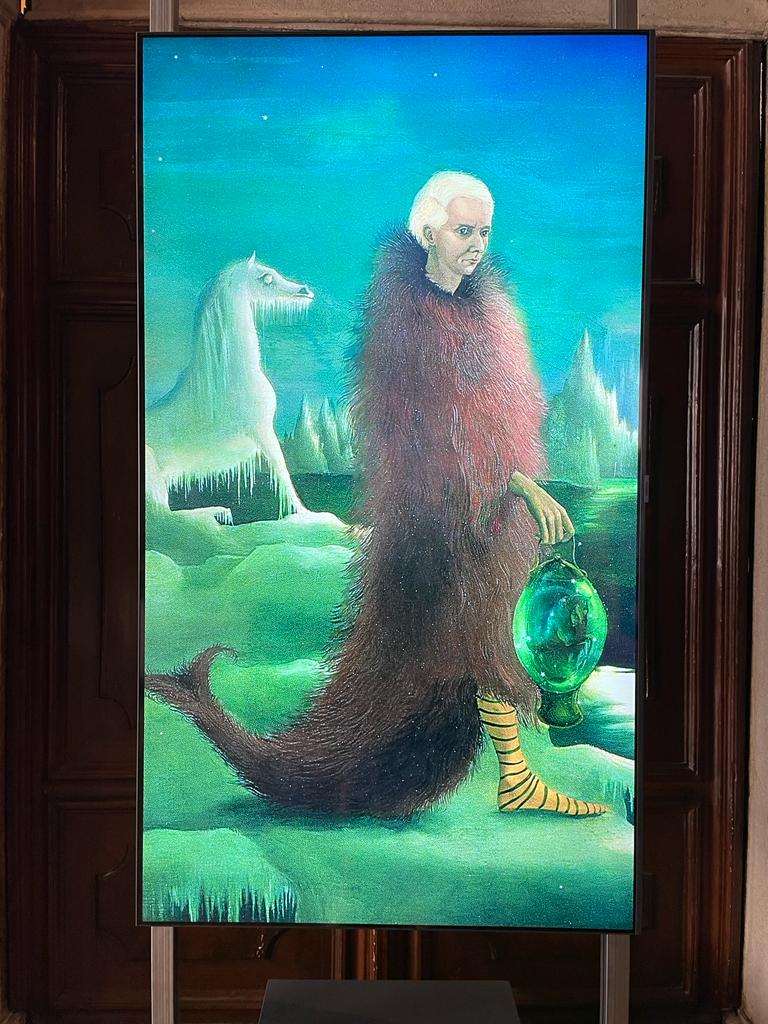

Indeed, I am the technical director of the collection and I am passionate about it. We work with more than one hundred and fifty works, 95% of which belong to living artists. From the first thoughts on cybernetics in the video art of Peter Weibel to the generative art of Alba Corral. All the works are of a different nature and this implies a maximum challenge, a knowledge of thousands of sub technologies, different operating systems and different interfaces. It is still a path that is being generated thanks also to the support of all the artists, but it is certainly a collective challenge that we face and we want our works to survive in the future.

If I have to give some advice, in order for our works to be enjoyed in the future, I would comment that it is important that we work with tools that we know very well, that we make them our own and little by little we feel that we control those supports absolutely. Our lines of code are our paint strokes and the screens, our canvases, appropriating their colors and their movements. This may sound a bit unpopular, but the field of collecting requires a certain security when it comes to a work working or being restored. We are also developing protocols for the collection that make it possible to arrange the craziest works, of course!

Jaime de los Ríos. Vortex, 2024

In “The problem of form”, your current exhibition at Arteko Gallery, from which we present a selection of digital pieces in Niio, you recover the connection between painting and algorithmic creation that underlies much of your work. The exhibition combines digital works with pieces on paper and digital printing on aluminum. At the current moment of maturity in your career, how do you conceive the role of digital art in relation to other forms of contemporary artistic creation? How has the exhibition been received in the context of a contemporary art gallery?

I’m really excited about exhibiting at Niio, the exhibition has expanded in an unimaginable way. Now it travels through the networks and sneaks into screens all over the world. It is a very personal work that above all I have been able to exhibit in my homeland. After several exhibitions in the Arteko gallery, I can say, and this seems to me very important, that people have made my art their own.

In times of globalization and the tentacular capacity of the Internet, it is common to think that the number of “likes” is more important than the number of people around you. This is why the exhibition has been very successful, even in terms of sales! And nowadays I would say that digital art is already part of contemporary art. Both art lovers and people who are more distant from the medium are already more familiar with this movement that speaks of issues they are aware of, and uses the same tools they use in their daily lives.

“For our works to be enjoyed in the future, it is important that our lines of code are our paint strokes and the screens our canvases.”