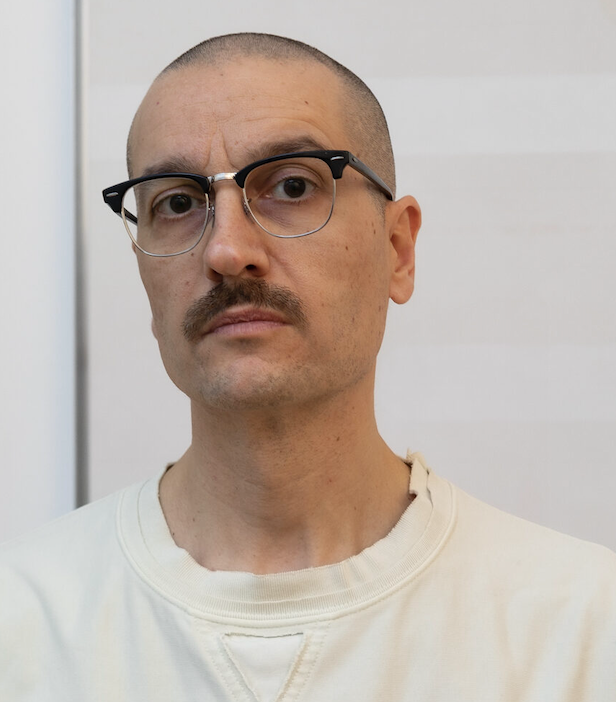

Pau Waelder

An early practitioner of net art, Carlo Zanni is among the first artists to explore the nascent opportunities for the online art market and reflect on how the web would impact on our sense of identity and privacy. With a painter’s vision, he has seen in the development of online platforms and graphical user interfaces a space of visual compositions in which the computer desktop becomes a landscape, and everything in it is a fiction.

He has also developed new forms of storytelling through web-based projects such as the “data cinema” trilogy: The Possible Ties Between Illness and Success (2006), My Temporary Visiting Position from the Sunset Terrace Bar (2007), and The Fifth Day (2009). In these online films, he combined a pre-defined narrative with data collected in real time from the same users who were watching the film, or from a distant webcam, or from different sources describing the social and political conditions of Egypt.

Carlo Zanni, The Fifth Day (2009)

Explore Zanni’s data cinema artworks

Embedded in his work as an artist, his research on alternative models to sell digital art has led to pioneering yet unrealized projects such as P€OPLE ¥ROM MAR$ (2012), an online platform dedicated to selling video art and fostering a community of creatives based on shared revenue, or ViBo (2014-2015), a “video book” aimed at facilitating the sale of video art at affordable prices in unlimited series. He collected his experiences with these models in the book Art in the Age of the Cloud (Diorama Editions, 2017).

Niio is proud to present two selections of artworks by Carlo Zanni: Data Cinema Anthology, which brings together the Data Cinema trilogy and an additional artwork, and Save Me for Later, a code-based artwork recently presented at Zanni’s solo exhibition Accept & Decline at OPR Gallery in Milan. In the following interview, the artist discusses the artworks presented in this exhibition, which can be visited until April 28th.

In this latest series you have come back to painting as a medium, after a long career focused on web-based art, but you keep exploring the same subjects. Can you take me through the main ideas in the Check-Out Paintings?

This cycle of paintings is part of a long-term investigation of the social and psychological role of eCommerce in our society. It stems from the memories of the eCommerce check-out pages: a final destination we all are funneled to, in every online buying process. The check-out pages of eCommerce sites represent a highly symbolic limbo that precedes the dopamine rush where we all hope to find shelter. A form of addiction, but as shown during the pandemic, also a lifeline.

“Our identity bounces between the happiness for buying, and the sense of guilt for having bought.”

Buying online is both a sort of pursuit of happiness as we have been taught by our society, both a way to escape reality, procrastinating any possible confrontation with ourselves. Our identity bounces between the happiness for buying, and the sense of guilt for having bought. Between the satisfaction of an increasingly frictionless, user-friendly, fast, and on-time experience; and the anxiety, and also the shame, for what this transient fake happiness often entails on a social, work, and human level for thousands of people: directly (shifts and working conditions, small local businesses), and indirectly (tax evasion of mega-corporations and environmental impact).

Unlike early works such as DTP Icons Paintings (2000), here you do not look for a realistic representation of the interface, but rather create almost abstract compositions, why is that?

True, because here is more about inner feelings than simple representation. It’s not witnessing from the outside but feeling from the inside, then trying to show a glimpse of it, if possible, in the real world. So the rationalist layout, typical of these pages, fades into memory, it turns into a dreamlike experience, into a psychological post-image, while some details of the transaction, such as measures, prices, and quantities, emerge from the background when one gets closer to the surface of the painting: they bring us back to reality.

The subtle color fields of these paintings make them very difficult to be mediated or “seen” online (e.g. on Instagram, or on a PDF), instead they open up and expand in front of the viewer when experienced for real. While our society continues to demand fast, easily communicable images, these paintings are slow, almost invisible, non-existent images, and they ask for something very precious: our time.

How did you achieve this faded effect in the canvases?

The color used in these works is acrylic mixed with water and in some cases acrylic medium. This way tones are soft and they mesh one into the other when seen from a certain distance, vaporizing the memory of the whole picture. I take advantage of the cutting plotter to write numbers and other “technical” details. I cut the letters in vinyl (negative) with a size that allows me to draw inside them with a sharp pencil without touching the vinyl edges. This way the sentences and the lettering look “straight” and “guided” from a distance, and handmade from a closer inspection.

“When you stick your nose onto the canvas, the work transforms from an abstract field into a condensed epic of our times.”

Formally speaking, the style of these paintings was born in response to a period of social isolation due to the pandemic, during which, as a balance, we have tried to mediate all the possible human activities: meetings, purchases, employment, leisure, study, culture… I felt the need to go the other way, working on something that could be only appreciated when seen in person.

If you want to find some roots, these works echo the mature practice of artist Agnes Martin, in the use of pencil and subtle water-based colors, but here all the “modernist” and “minimalist” values of the time are almost gone. So all the pencil details and most of the color fields are only visible when you stick your nose onto the canvas, and the work transforms from an abstract, almost white, field, into a condensed epic of our times touching themes such as anxiety, desire, happiness, fear, gender identity, pandemics, politics, tragedies, wars.

While the paintings look almost abstract, they also contain references to the present, as is frequently found in your web-based artworks, what role do these references play?

The paintings dig into our daily culture and politics, for instance by discreetly showing disclaimers referring to the current Ukraine war. (Since February 2022, many eCommerce added such disclaimers for multiple reasons: from giving updated shipping info to giving their support to the Ukrainians). I see these paintings as a vehicle for meditation, an attempt to temporarily alienate ourselves from this endless moment of upheaval and unrest; while being violently dragged back to reality when we get closer to the surface: they are a way to extract some time from our hectic lives to sense the delicacy and fragility of our body and the transience of happiness while diving into our time.

While they are very different artworks, I would point out to Average Shoveler (2004) as having a similar approach in terms of its meditative aspect and the connection to real life events. In that work, which was commissioned by Rhizome, I created an online video game in which the player controls a man who has to shovel the snow falling on the streets of New York. Each time he does, several images taken from CNN and other news outlets in real time pop up and disappear. Additionally, some non-player characters stop and speak out news headlines. The main character invariably ends up dying of exhaustion, unable to shovel the incessant amount of snow. But the game also includes some secret spaces meant for the player to relax and just observe the scene, distanced from the gameplay. In a way, these paintings also provide that distanced space of observation while having these subtle hooks to reality.

Carlo Zanni, Average Shoveler (2004)

Talking about hooks, you describe some elements in the paintings as “clickbait,” can you elaborate on that?

Yes, the dark dots and solid-colored shapes (lines, rectangles, circles) that appear in some of the paintings are what I call “clickbaits” for one’s eyes. Seen from afar these canvases look pretty white and empty, but these dots stand out and catch your attention. They work similarly to how advertising plays with colors, double meanings, and impressive images to stand out in a visually saturated landscape.

They also remind of the so-called “dark patterns”, which are interface design strategies quite common in e-commerce pages, that are meant to fool the user into doing what the vendor wants them to do, such as sign up for a newsletter, add an extra service, or choose the most expensive option among several choices. In my paintings, the shapes intend to lure you into looking closely at the painting and finding what it is actually about. However, I would say that while clickbait is content that over-promises and under-delivers, in my paintings I under-promise and over-deliver 🙂

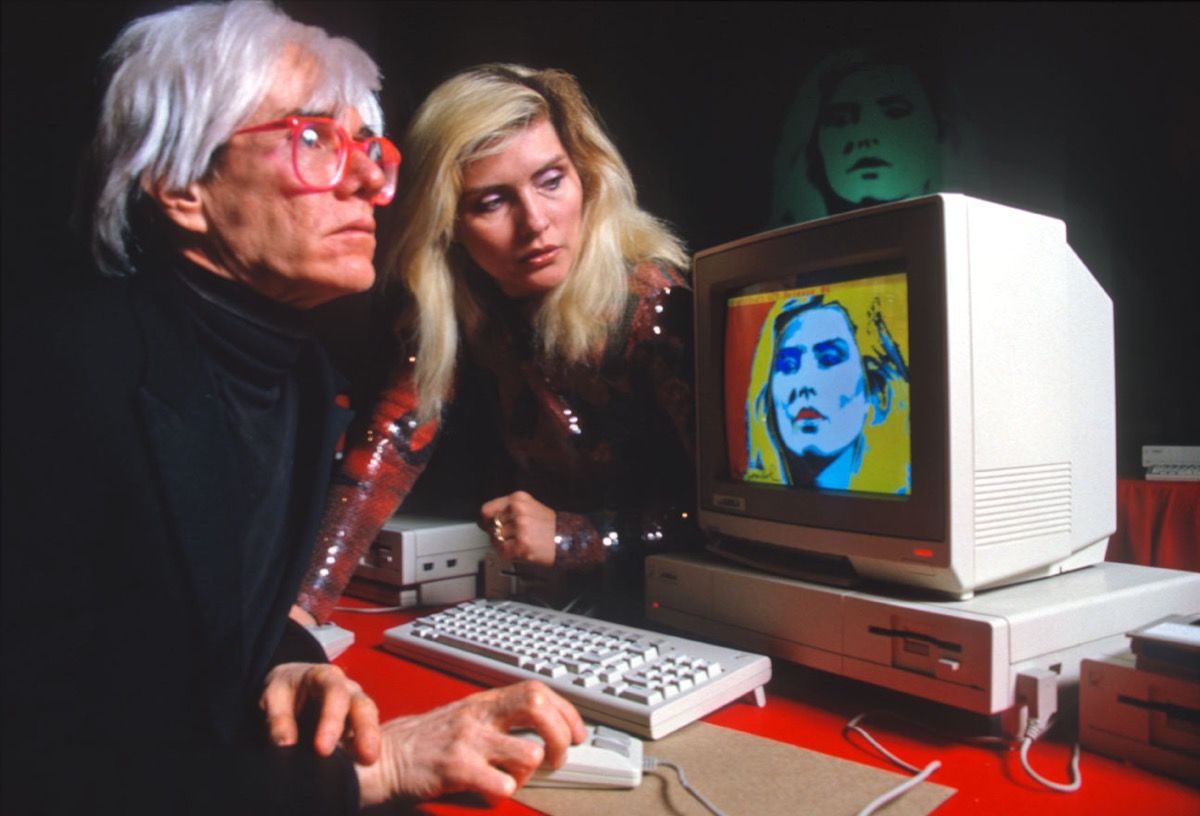

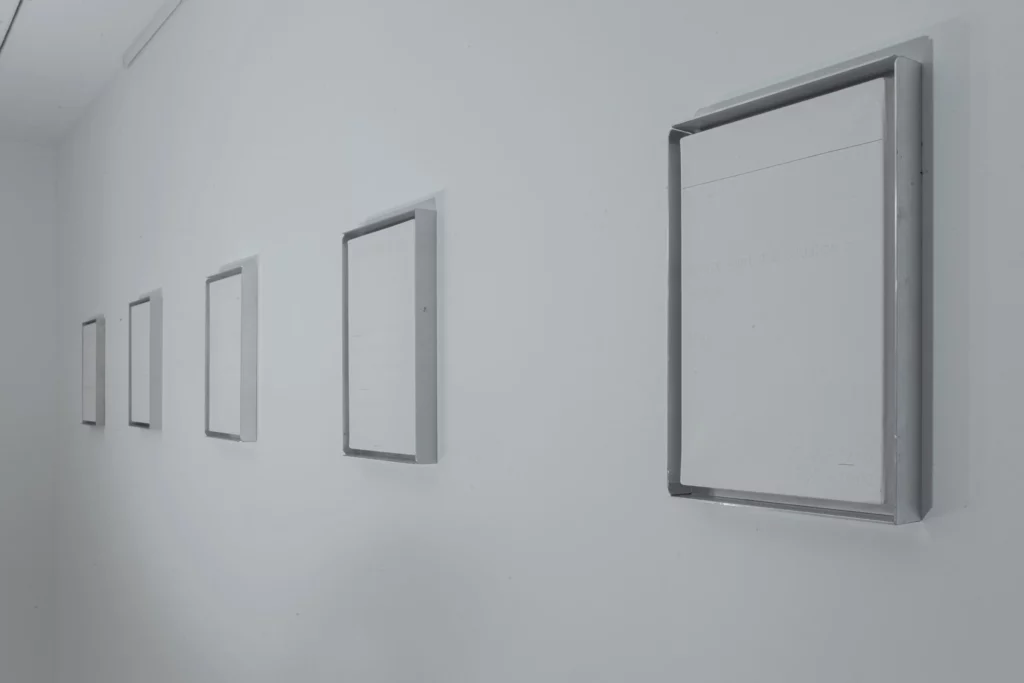

Carlo Zanni, Save Me for Later (2022)

Save me for later (2022) is also an intriguing artwork in the sense that it is not what it appears to be, and it connects with a concept you have explored over the years, which is the computer screen as a landscape

“Save me for later” is actually a bot browsing Amazon.com, continuously adding products to the cart that is visible in the right sidebar. When the cart reaches its limit, it automatically moves products to the “saved for later list”, making room for the new freshly added ones. The bot embeds a floating window with the webcam stream framing me while performing. This repetitive and almost hypnotic performance, with apparently no beginning and no end, speaks of the type of procrastination we all carry out while browsing e-commerce sites, looking for products that will bring us happiness and make our lives better.

As with the paintings, the experience of isolation during the pandemic was key to conceiving this artwork, in which the computer screen becomes a landscape, a place of escapism and daydreaming. The performance is consciously slow and cryptic, and as it is playing out in real time, in the real Amazon website, the items that appear reflect our present time just as the subtle writings on the paintings take us back to the world we are living in. For instance, when I first ran the program, the bot frequently picked up COVID-19 self-tests, which at some point were very much in demand and right now are almost forgotten.

“This repetitive and almost hypnotic performance speaks of the type of procrastination we all carry out while browsing e-commerce sites, looking for products that will bring us happiness and make our lives better”

I see this project also as a vehicle for meditation, an attempt to alienate ourselves momentarily from our daily lives and our anxieties (so the title “Save me for later”). And behind the activity itself, what you see on the screen that is apparently me browsing the Amazon site but is in fact an automated process carried out by a computer program, is an interesting exchange of data. Data collected by the Amazon site about this meaningless routine (constantly adding items to the cart without ever checking out), data displayed by Amazon about the articles on sale, data that is processed by Amazon’s algorithm to display new items related to previously selected products.

See a two-hour excerpt of Zanni’s endless automated performance on Amazon

Data is for me what gravity probably was for Bas Jan Ader. “The artist’s body as gravity makes itself its master.” These mysterious words were used by Bas Jan Ader to describe his short films Falling I (Los Angeles) and Falling II (Amsterdam) when he showed them in Düsseldorf in 1971. He was playing with gravity, he was becoming gravity, accepting its outcome: failures, fragilities, spiritualism, poetry, meditation, ascension.

I feel that I use data in a sort of similar way, accepting the fact that most of my works will cease to exist quite soon after their birth. By using data from media outlets such as CNN, tools from Google, data collected from users, and so on, I consciously open my work to a vulnerability as the price to pay for creating a work that is always connected to the present and fed by data that circulates online. Then, an API is changed, a tool is discontinued, and the artwork cannot exist anymore. Sometimes you can fix them, sometimes you just don’t want to do it.

Other times you start again from scratch as recently I did with Cookie Portrait (2002-2022), a work about online identity and privacy that had to be rewritten when it was launched at OPR Gallery last year, 20 years after it was first created. This work is based on the same cookie technology that is used – for instance – for the internal session management of an eCommerce site and more generally for user profiling and marketing activities. This work reminds us that, in our online existence, we are made of data. The body is thus the sum total of your data, the artwork is a temporary and transient experience of something elusive, like our own existence is.